![]()

by PROFESSOR E. Rutherford, F.R.S., and H. ROBINSON, M.SC.,

Demonstrator and Assistant Lecturer in the University of Manchester

From the Philosophical Magazine for February 1913, ser. 6, xxv, pp. 312–30

SINCE the initial discovery of the rapid and continuous emission of heat from radium by P. Curie and Laborde in 1903, a number of investigations have been made by various methods to determine with accuracy the rate of emission of heat. Among the more important of these may be mentioned the determination of Curie and Dewar* by means of a liquid air and liquid hydrogen calorimeter; of Angström;† and of Schweidler and Hess‡ by balancing the heating effect of radium against that due to an electric current; and of Callendar§ by a special balance method. It is difficult to compare the actual values found on account of the uncertainty as to the relative purity of the radium preparations employed by the different experimenters. The most definite value is that recently obtained by Meyer and Hess|| using part of the material purified by Hönigschmid in his determination of the atomic weight of radium. As a result of a series of measurements, they found that 1 gram of radium in equilibrium with its short-lived products produces heat at the rate of 132·3 gram calories per hour.

Rutherford and Barnesl¶ in 1904 made an analysis of the distribution of the heat emission between radium and its products. They showed that less than one quarter of the heat emission of radium in radioactive equilibrium was due to radium itself. The emanation and its products, radium A, B, and C, supplied more than three quarters of the total. The heating effect of the emanation was shown to decay exponentially with the same period as its activity, while the heating effect of the active deposit after removal of the emanation was found to decrease very approximately at the same rate as its activity measured by the α rays. The results showed clearly that the heat emission of radium was a necessary consequence of the emission of α rays, and was approximately a measure of the kinetic energy of the expelled α particles. If this were the case, all radioactive substances should emit heat in amount proportional to the energy of their own radiations absorbed by the active matter or the envelope surrounding them. This general conclusion has been indirectly confirmed by measurements of the heating effect of a number of radioactive substances. Duane* showed that the heating effect of a preparation of polonium was of about the value to be expected from the energy of the α particles emitted, while the experiments of Pegram and Webb† on thorium and of Poole‡ on pitchblende showed that the heat emission in these cases was of about the magnitude to be expected theoretically from their activity.

It is of great interest to settle definitely whether the heat of radium and other radioactive substances is a direct measure of the energy of the absorbed radiations. Since the emission of the radiations accompanies the transformation of the atoms, it is not apriori impossible that, quite apart from the energy emitted in the form of α, β, or γ rays, heat may be emitted or absorbed in consequence of the rearrangements of the constituents to form new atoms.

The recent proof by Geiger and Nuttall§ that there appears to be a definite relation between the period of transformation of a substance and the velocity of expulsion of its α particles, suggests the possibility that the heating effect of any α-ray product might not after all be a measure of the energy of the expelled a particles. For example, it might be supposed that the slower velocity of expulsion of the α particle from a long-period product might be due to a slow and long-continued loss of energy by radiation from the a particle before it escaped from the atom. If this were the case, it might be expected that the total heating effect of an α-ray product might prove considerably greater than the energy of the expelled α particles.

In order to throw light on these points, experiments have been made to determine as accurately as possible:—

(1) The distribution of the heating effect amongst its three quick-period products, radium A, radium B, and radium C.

(2) The heating effect of the radium emanation.

(3) The agreement between the observed heat emission of the emanation and its products and the value calculated on the assumption that the heat emission is a measure of the absorbed radiations.

(4) The heating effect due to the β and γ rays.

It was also of interest to test whether the product radium B, which emits no α rays but only β and γ rays, contributed a detectable amount to the heat emission of the active deposit.

Method of Experiment

In order to test these points, it was essential to employ a method whereby rapidly changing heating effects could be followed with ease and accuracy. A sufficient quantity of radium emanation was available to produce comparatively large heating effects. It was consequently not necessary to employ one of the more sensitive methods for measuring small heating effects, such as have been devised by Callendar and Duane.

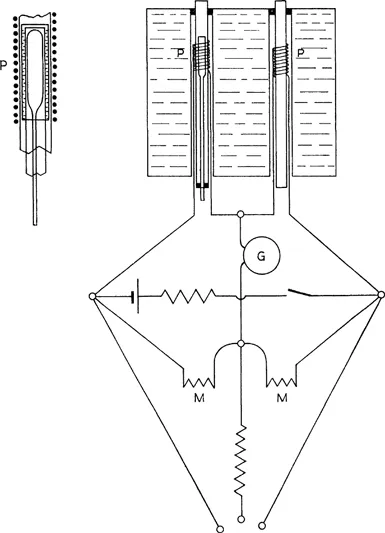

The general arrangement was similar to that employed in 1904 by Rutherford and Barnes for a like purpose. Two equal coils, P, P, fig. 1, about 2·5 cm. long, were made of covered platinum wire of diameter 0·004 cm. and length 100–300 cm., and wound on thin glass tubes of 5·5 mm. diameter. These platinum coils of nearly equal resistance formed two arms of a Wheatstone bridge, while the ratio arms consisted of two equal coils, M, M, of manganin wire, each of about the same resistance as the platinum coils, and wound together on the same spool and immersed in oil. The platinum coils had a resistance varying between 15 and 45 ohms in the various experiments. The glass tubes on which the platinum coils were wound were placed in brass tubes passing through a water-bath. When a specially steady balance was required, the water-bath was completely enclosed in a box and surrounded with lagging to reduce the changes of temperature to a minimum. In most of the experiments the correction for change of balance during the time of a complete experiment was small and easily allowed for. By means of an adjustable resistance in parallel with one of the coils, a nearly exact balance was readily obtained. A Siemens and Halske moving-coil galvanometer was employed of resistance 100 ohms. This had the sensibility required, and was found to be very steady and proved in every way suitable.

The current through the platinum coils never exceeded 1/100 ampere, and was generally about 1/200 ampere.

A calibration of the scale of the galvanometer was made by placing a heating-coil of small dimensions of covered manganin wire within one of the platinum coils, and noting the steady deflexion when known currents were sent through it. It was found that the deflexion of the galvanometer from the balance zero was very nearly proportional to the heating effect of the manganin coil, for the range of deflexion employed, viz. 400 scale-divisions. The deflexion thus served as a direct measure of the heating effect.

§ 1. Distribution of the Heat Emission between the Emanation and its Products

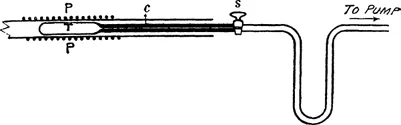

A quantity of emanation of about 50 millicuries was introduced into a thin-walled glass tube T (fig. 2) connected by a capillary tube C to a small stopcock S. The tube was attached to a mercury-pump by the aid of which the emanation could be purified and compressed into the emanation-tube. The position of the latter was adjusted to lie in the centre of one of the platinum coils.

As it was necessary to leave the emanation for about 5 hours in the tube for equilibrium to be reached with its successive products, it was desirable to arrange that the emanation-tube could be removed outside the water-bath at intervals to test for any change in the balance. The emanation-tube was kept fixed to the pump, but the water-bath was moved backwards along the direction of the axis of the emanation-tube. For this purpose, the water-bath was mounted on metal guide...