![]()

1

The Problem

The human mind encompasses an enormous number of memories. Whether all memories that were ever established still persist is a matter for coffee debates; the fact remains that the usual adult possesses an amount of information in memory that essentially defies measurement. Represented among these memories are those reflecting experiences that occurred at definite points in time. A chronicle of these memories would in one sense constitute the history of the individual. A chronicle implies an ordering of events that corresponds with true ordering. Major events in our lives, such as eighth grade graduation, high school graduation, marriage, and retirement, would be ordered properly because there is a necessary order to such events. But when we ask about memories that are less inevitably ordered, we begin to be less certain of the chronicle. Did your father lose his job before or after your second child was born? Did you become a member of the bowling team before or after you remodeled your kitchen? When we ask such questions, we begin to see that many events that are well remembered seem to have, at best, only a crude location in the chronicle of our experiences.

The problem of central interest in this book is the nature of the temporal coding of memories. Just how this became a problem of moment will be detailed later. It is sufficient at this point to indicate that our attempts to solve certain problems of memory functioning led me to believe that differences in temporal coding of memories were implicated. We were thus led to undertake some experimental work to supplement evidence available in the literature; the intent was to get at least a preliminary understanding of the variables that govern our ability, or lack of it, to distinguish by memory the ordering of events in time.

It seems to me that most of the evidence available, as well as evidence that arises from introspection, leads to a conclusion that our ability to identify points in time at which particular memories were established is very poorly developed. One wonders why evolutionary changes (purported to have occurred over the centuries as adaptive changes) have not given us memories that are in some way intrinsically dated. Why has nature treated us so uncharitably? Had there been an ageless observer at the sparkling moment of the creation of the egg–or of the hen–we would be no better off than we are today, for I am sure the observer would have soon forgotten which came first.

It might be presumed by some that, because our ability to date memories is so poorly developed, such abilities are of little consequence for our welfare. Or, without implying a cause: Of what importance is the ability to order memories correctly? Of what importance is it to remember that the kitchen was remodeled before the time a bowling team was formed? Our legal system depends heavily upon an external dating system (a calendar system) to establish an order of events that can be accepted by all. At the same time, it seems beyond a doubt that justice may not have been served in many, many cases where the order of events was determined by the testimony of a witness. If a decision concerning the guilt or innocence of a citizen charged with murder depended upon the memory of a witness as to whether he had heard a gunshot before or after he heard the squealing of automobile tires, I would be uncomfortable with the decision. A recent newspaper story told of a disagreement between the Internal Revenue Service and a businessman over the deductions he had taken in calculating his income tax. These deductions were for business expenses, expenses which consisted primarily of costs for luncheons and dinners for his clients. Many of the witnesses testified under oath that they had indeed been recipients of the luncheons and dinners, but when the Internal Revenue Service asked them for specific dates they were quite unable to reconstruct the dates. It has been reported (Gibson & Levin, 1975) that children afflicted with dyslexia are particularly inadequate in their memory for the temporal ordering of events.

The above is merely to suggest that our inability to tie our memories for events to certain points in time, and thereby to order the events accurately, is not without impact on our lives. Still, we are able, within some margin of error, to associate our memories with their times of formation, and the question is how we are capable of such dating at all.

In the first two chapters, I will establish the contours of the problem as I see them. For the initial step, I will report three rather diverse studies as a means of illustrating procedures and data that are said to deal with temporal coding.

EXPERIMENT 1

We brought together 24 brief statements describing events that had occurred from 1968 to 1975. Pretesting indicated that most college students would remember that these events had indeed occurred, although it is not definite that the memories for them were established at the time of their occurrence. The descriptions of the 24 events, along with the month and year of occurrence, are given in Table 1. They are divided into three groups of eight each (three forms) for reasons which will become clear momentarily. In Table 1 the events are listed in order from most recent to least recent, although on the test sheet given to the subjects the statements were randomized. Each subject supplied a date for only 8 of the 24 events, and the subgroups of 8 events each are identified as “forms.”

Students in a large, advanced undergraduate lecture course served as subjects, all being tested simultaneously. The eight statements were printed on a single sheet. After each statement, two blanks occurred: one identified as “year,” the other as “month.” The three forms were interlaced before distribution to the subjects, so we assume that the three subgroups were equivalent in their knowledge of the events. The instructions at the top of each sheet were as follows:

Below are listed eight events that have occurred in relatively recent years. The events were so momentous and were so widely reported by TV, radio, and newspapers that most college students will remember that the events did indeed happen. Our interest is with your memory concerning when each event happened. There is some belief among those who study memory phenomena that our knowledge of the position of an event in the flow of events is relatively poor. In fact, however, there is very little systematic evidence on the matter. This “test” is an attempt to get preliminary evidence on the accuracy of our memory for the placement of events in time.

TABLE 1

Descriptions of the 24 Events for Which Subjects Were Asked to Supply a Date of Occurrence (Month and Year) in Experiment 1

| Description of events | Date of occurrence |

Form 1 | |

James R. Hoffa reported missing | 7/75 |

The tidal-basin incident involving Wilbur Mills | 10/74 |

Richard Nixon resigned the presidency | 8/74 |

Billie Jean King defeated Bobby Riggs in tennis | 9/73 |

Governor George Wallace shot | 5/72 |

Attica (New York) prison riot | 9/71 |

The tragic incident at Chappaquiddick Island involving Ted Kennedy | 7/69 |

Martin Luther King assasinated | 4/68 |

Form 2 | |

The Apollo-Soyuz linkup in space | 7/75 |

Hank Aaron established a new home-run record | 4/74 |

Patty Hearst kidnapped | 2/74 |

Spiro T. Agnew resigned the vice presidency | 10/73 |

President Nixon visited mainland China | 2/72 |

Kent State students killed | 5/70 |

The first man stepped on the moon | 7/69 |

Robert Kennedy shot | 6/68 |

Form 3 | |

Death of Aristotle Onassis | 3/75 |

Evel Knievel failed in his attempt to rocket across the Snake River Canyon | 9/74 |

Alexander Solzhenitsyn exiled from Russia | 2/74 |

Former President Lyndon B. Johnson died | 1/73 |

Baseball star Robert Clemente killed in plane crash | 12/72 |

Disney World in Florida opened | 10/71 |

Former President Eisenhower died | 3/69 |

U.S.S. Pueblo captured by North Koreans | 1/68 |

Note: Each subject was given eight statements, thus there were three forms.

We would like you to give your best guess as to the year and month during which each of the eight events occurred. You may find this difficult, but please fill in each blank–the year and the month–for each event, even if you feel that your estimates are more or less guesses.

The subjects also entered their ages. The test was unpaced, with most subjects finishing within five minutes.

Some blanks were left unfilled by some subjects. These test sheets were discarded. In addition, all subjects 23 years of age and over were eliminated. Other sheets were discarded randomly to equalize the groups (forms) at 36 subjects each. The data to be presented were based on 108 subjects, with the number of subjects in the five age groups of 18, 19, 20, 21, and 22 years being 6, 30, 46, 21, and 5, respectively.

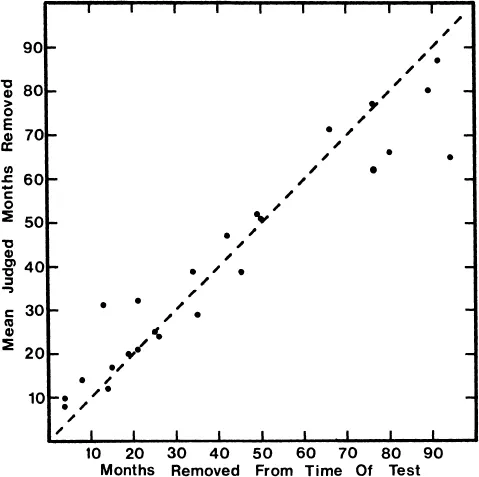

The subjects made an estimate of the month and year for each of the events. The test was given to the subjects in November 1975. Therefore, as a metric, the true age of an event was calculated in months backward from November 1975. Thus, the event concerning James R. Hoffa was 4 months removed from November 1975, the Wilbur Mills incident 13 months removed, and so on, until the oldest event on Form 1 (the assassination of Martin Luther King) was 91 months removed from the point in time at which the subjects made their judgments. The dates given by the subjects were likewise transformed into months removed from November 1975. A mean for these scores for each event was determined to get an estimate of group accuracy. The plot in Figure 1 shows the outcome, with the diagonal line indicating the true number of months by which the events were removed from November 1975.

Although the collective judgments could probably not be used to replace a calendar, the correspondence between the true number of months removed and judged number of months is quite high, the product–moment correlation being .96 for the 24 events. Other evidence might lead to the expectation that events close in time would be judged to have occurred further back in time than was actually true and events very remote in time would be judged to have occurred at times less remote than was true. As can be seen in Figure 1, there is at best only a suggestion of this in the data. It has been reported (Linton, 1975) that errors in estimates increase in magnitude as the memory gets older. Statistically, this would mean that the standard deviation of the judgments would increase the further back the event occurred. This was generally true, but there were many exceptions for particular events.

FIGURE 1. Mean judged months removed (from November, 1975) for 24 events, differing in number of months removed. The diagonal line represents perfect correspondence between age of events and judged age (Experiment 1).

We next asked about the relative ordering of the events by the individual subject. The true orderings were correlated with the ordering inferred from the eight dates assigned the events for each subject. The mean of these correlations was .79, and all 108 were positive. The lowest correlation observed was .08, but only 2 of the 108 subjects ordered the events perfectly. A hit may be defined as assigning the correct month and year for an event. The hits averaged just under one (.98), and 45 of the subjects had no hits. In terms of events, the maximum number of hits was 50 percent (“Nixon resigned the presidency”), but no hits were observed for three of the events. The average error by which the subjects missed was 15.01 months, with a range of from 1.38 months (approximately 40 days) to 35.38 months (just under three years).

Decades of psychophysical research would lead to the expectation that, the closer two events were in time, the greater the likelihood that the two events would be misordered in time. For each form, the number of errors made by each subject in ordering was determined for all combinations of two events. Thus, if the subject assigned an older date to “Hoffa reported missing” than to “the King-Riggs tennis match,” it was counted as an error. For each form, 28 such comparisons could be made, or 84 across the three forms. These 84 combinations were grouped according to the time separating the two events, each group spanning 10 months, so that nine groups covered the entire range. For the two-event combinations falling within each grouping, the percent error was determined, and these values have been plotted in Figure 2. Expectations were fully realized; the greater the time separating the two...