![]()

1

Do Animals Have Memory?

Frank T. Ruggiero1

Steven F. Flagg2

INTRODUCTION

Common experience indicates that animals remember things–dogs know their masters, homing pigeons can find their roosting place, bait-shy rats avoid poisoned food. Therefore, the following anecdote may come as a surprise. Several years ago a fellow graduate student was engaged in defending his thesis, which was concerned with imprinting in chickens. At the outset, the student discussed changes in the animals’ memory that had occurred during the experiment. One of the student’s committee members was from the philosophy department and midway through this presentation the philosopher stopped the discussion, proclaiming that he could not understand why the student persisted in using the word memory to describe the animals’ behavior. After all, he pointed out, “Aristotle has told us that animals are incapable of higher processes and therefore, they cannot possess memory!” Having said that, he left.

To better understand the philosopher’s consternation and the purpose of this chapter it is necessary to consider briefly the historical context of animal memory. Since the time of Aristotle, man has been regarded as different from animals because he possesses a reasoning ability, based on a spoken language. Thinking was, and often still is, equated with linguistic ability. For instance, until the 16th century, when a Spanish nobleman’s deaf son was taught to read and write, the deaf were legally considered to be subhuman because they did not manifest speech (Furth, 1966). Such thinking reflects the view that, man, by virtue of his verbal ability, is capable of actively recalling the past (i.e., generating information about a past event in the absence of the original event), whereas nonverbal organisms are capable of recognition at best. If the term “memory” is restricted to instances of active recall, we can begin to understand the philosophy professor’s claim that animals do not have memory.

In this chapter we examine three distinct types of memory, the first two corresponding roughly to recognition and recall. We do this not because we hope to deny or delimit mnemonic capabilities in animals, but because different theoretical questions arise in considering these different kinds or aspects of memory.

STIMULUS-RESPONSE MEMORY

The first type of memory we consider, S–R memory, has often gone under the designator “retention.” Because learning would be impossible without some memory, the study of changes in the strength of associations comprising learning was compatible with the S–R learning theories of Hull (1943) and Spence (1936, 1937) which dominated research in the 1930s and 1940s. The S–R bond was all important, and because memory was not defined independently from the S–R bond the use of the term “memory” seemed to be an unnecessary additional hypothetical construct. Learning experiments examined the formation of the S–R bond and retention tests, when given, were concerned with determining how long this S–R bond lasted. (See chapter 2 for further analysis of the influence of the learning orientation on the study of memory.) For the purpose of this chapter we call this conceptualization of memory S–R memory.

S–R memory was investigated in animals using various learning paradigms. Typically an animal was trained to a criterion on a task and then tested or retrained on that task days, months, or years later. If the subject performed better on the latter exposure to the task than control animals with no prior experience on the tasks, the animal was said to have retained the original training. It was soon found that animals showed remarkable retention for well-learned tasks and the investigator’s interest often faded at that point. Instances of forgetting were interpreted mainly in terms of interference caused by new and prior learning (see Gleitman, 1971).

In terms of the distinction between recall and recognition, virtually all studies in the S–R framework fall under the domain of recognition–the appropriate stimulus conditions are presented for the retention tests and the animal either does or does not then behave appropriately. In these tasks there is an easily identifiable stimulus that can elicit the response of the animal.

The very nature of the tasks used to study animal memory resulted in animal memory being easily interpreted in the classical S–R terms. No widely used animal paradigm readily comes to mind that corresponds to studies of recall in human subjects. Yet, as we shall see, memory in animals is not limited to the retention of learned acts.

REPRESENTATIONAL MEMORY

Even in the face of S–R associationisms’ heavy influence, there was research aimed at determining whether animal memory might consist of more than response tendencies. That is, perhaps animals have an independent representation of a stimulus event, one that is stored in memory and can be used (recalled) in the absence of that stimulus. Memory that is defined independently of the S–R bond and that can be assessed in a number of ways, not just as a conditioned response to a stimulus, shall be referred to as representational memory. Historically, Tolman’s S–S psychology seems most compatible with representational memory. Indeed, Tolman was criticized for not having ready rules for translating memory into performance.

A clear demonstration of representational memory in animals is difficult because most nonverbal memory tests involve recognition and, by definition, there is always a stimulus present to elicit the response in these tasks. In order to demonstrate representational memory, one must devise a test where the stimulus is not present at the time of the retention test, or one in which there has been no opportunity to form a S–R bond.

Delayed Response Problems

Hunter’s (1913) classic work on the delayed-response problem was perhaps the first attempt to determine experimentally whether animals have representational memory. The paradigm was designed to analyze “mammalian behavior under conditions where the determining stimulus is absent at the time of response” (Hunter, 1913, p. 1). To assess whether or not animals could react on the basis of “mental imagery,” rats, dogs, raccoons, and children from two age groups were taught to associate a light at one of three food boxes with reward. After this training the light at the food box was extinguished before the subject responded, requiring the subject to remember where the light had been. No response was made at the time of stimulus presentation.

Different time delays were interposed between the offset of the stimulus light and raising the clear glass restraining chamber. Raising the restraining chamber permitted the subject to run to one of the food boxes. Hunter was primarily interested in two things, the maximum delay the different species could wait and how they were mediating the delay. Because the subject had to respond in the absence of the stimulus that had previously guided his reaction (the light), this seemed to Hunter to offer the potential of testing for representational memory in animals. In his words: “If a selective response has been initiated and controlled by a certain stimulus, and if the response can still be made successfully in the absence of that stimulus, then the subject must be using something that functions for the stimulus in initiating and guiding the correct response” (p. 2). Restated in the terminology used in this chapter, if the stimulus (light) is not there at the time of the response, memory must be more than a S–R bond. There must be a representation of the light held in memory that can be used even when the light is not present.

On the basis of behavioral observations made during the delay period, Hunter concluded that four levels of learning were needed to encompass the learning abilities of animals and children: (1) inability to profit from experience; (2) trial and error; (3) sensory thought; and (4) imaginal representation. He classified the behavior of his rats and dogs as trial and error, concluding that they were only capable of mediating the delay through the use of bodily orientation. Raccoons and young children (2–3 years of age) could use orientation cues or not and still respond well above chance. He felt their behavior could be regarded as an example of “sensory thought.” Only in the case of the older children (5–7 years of age) would Hunter grant the ability of imaginai representation in memory.

Body Orientation and Memory

Although Hunter was asking an important question about memory, his conclusions, concerning the importance of bodily orientation for memory in animals, were both premature and unfortunate for the development of animal memory research. His results were biased by the specific nature of his training procedures, which encouraged orienting responses (Weiskrantz, 1968). Ample evidence is available indicating that rats can solve various delayed-response problems without the aid of bodily orientation (Maier & Schneirla, 1935; Ladieu, 1944). In particular, investigators have reported that monkeys and apes can readily solve complex delayed-response problems over long delay periods without the aid of orientation cues (Tinklepaugh, 1928, 1932; Yerkes & Yerkes, 1928; Gleitman, Wilson, Herman, & Rescorla, 1963; Weiskrantz, 1968; Miles, 1971; Medin & Davis, 1974). In fact, the use of body orientation seems to be a nonpreferred strategy used by “less capable animals” (Harlow, Uehling, & Maslow, 1932) and one that is not spontaneously adopted (Nissen, Carpenter, & Cowles, 1936).

If delayed-response performance involves more than S–R memory, then this paradigm may provide an important tool for asking questions about representational memory. However, even though covert or overt orientation does not seem to provide the basis for delayed-response performance, these forms of orientation have always lurked as potentially confounding variables. Several years ago we began some work aimed at examining representational memory in monkeys, with orienting responses controlled. The problem is not so simple as it may seem, for we desire a technique for controlling orientation that does not otherwise disrupt performance. For instance, simply lowering the opaque screen of the Wisconsin General Test Apparatus (WGTA) during delay intervals does not suffice, for Motiff, DeKock, and Davis (1969) have demonstrated that this procedure may disrupt performance simply because lowering the screen normally is a signal that the current trial is over. The next several paragraphs describe our efforts to use alternative techniques to control orientation.

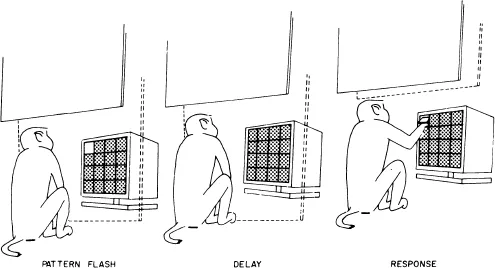

Basic memory as pattern reproduction (MPR) task. Because we will make frequent reference to it, the matrix pattern reproduction task illustrated in Fig. 1.1 will be described in some detail. The visual display equipment consisted of a 4 × 4 display of contiguous, translucent plastic panels. Each panel measured 6.4 × 6.4 × .9 cm and was the front wall or door of a 6.4 × 6.4 × 7.6 cm metal box. The door panel was hinged so that the animal could push on it and thereby gain access to a raisin reward lying on an elevated pad inside the box. The pad raised the food reward above the floor of the box so that the animal could not see it through the slight space at the bottom of the door. There were five lamps per cell, which were used to illuminate the plastic door. They were located at the back of each of the 16 boxes. Each of the lamps in a cell was a different color–aircraft red, aircraft blue, aircraft green, aircraft yellow (Woodson & Conover, 1965), or clear. The colored lights were obtained by placing commercially made rubber filters over clear 28 V lamps. The boxes also contained a microswitch that was activated when the door opened, allowing the light to come back on if the animal chose the previously illuminated cell. The entire 4 × 4 matrix display unit was mounted on a revolving base, in a modified WGTA, so that it could be turned 90° away from the animal to allow the experimenter to bait the correct cells of the matrix display. The stimulus conditions, response delays, and all other experimental conditions were controlled by feeding a punched card into a 80-column, static card reader which operated a solid state logic system.

FIG. 1.1 Display conditions for the basic MPR task. The nonshaded cell represents illumination of the stimulus cell with white light, and the dotted lines show the positions of the two-way, mirror glass viewing screen during the trial. For the duration of the delay phase the animal cannot see the matrix display. It is shown here for illustration purposes. [After Borkhuis, Davis & Medin, 1971. Copyright (1971) by the American Psychological Association and reproduced by permission.]

On a typical trial, the experimenter programmed the equipment to deliver the appropriate experimental conditions. He then baited the correct cell with a raisin, rotated the display 90° into position facing the animals, and raised the opaque screen of the WGTA to initiate the trial. The particular stimulus configuration could be seen by the animal through the viewing screen, which could be raised immediately or left in place for the duration of a variable response delay. The animal was allowed to respond to one of the cells after the viewing screen was raised. If he chose the correct cell he found a raisin in the cell, and the cell light reilluminated, confirming the response. This sequence is diagrammed schematically in Fig. 1.1.

In the only previously reported pattern reproduction task that controlled for orienting responses in monkeys, Riopelle (1959) lowered the opaque screen of his WGTA during the response delay to eliminate his monkeys’ view of his horizontal, 1 × 5 matrix display. He reasoned that if his animals were fixating on the correct square during the delay, this procedure should disrupt performance. The manipulation was so disruptive that Riopelle had to stop the experiment after 10 days of testing because of balks and generally uncooperative behavior. The little bit of data he collected showed a drop from 80% correct, with a view of the stimulus display, to 50% without a view of the display. (Chance in this situation was 20%.) Some of the decrement in the animals’ performance may be associated with the fact that lowering the screen was also the signal for the end of the trial.

Toward–away problem. In an attempt to test the generality of Riopelle’s findings (Ruggiero, 1974) the rhesus monkeys at Washington State University (Davis, 1974) were presented with one-light problems in the MPR paradigm and their view of the 4 × 4 matrix display was eliminated by turning the box away from the animal during the response delay. On toward trials the matrix display remained in place, facing each subject throughout the trial. On away trials the matrix display was turned 90° from the animal as soon as the stimulus light extinguished, and after a delay of 0, 3, 6, or 12 sec the box was turned back into position facing the animal.

The away procedure was very disruptive to MPR performance; it reduced the level of performance on the other delays from 80% correct to 28% correct, better than doubled the number of errors at all delays, and flattened out the negatively accelerated memory curve normally obtained in this paradigm. Because it was well known that old world monkeys could solve delayed-response problems without the use of bodily orientation cues, it was not clear why a view of the display was so important to maintaining performance.

A second study was conducted to determine whether the performance decrement resulted from insufficient time to encode the stimulus position. The same procedure as described above was used, except that on away trials there was a 1-sec delay before the box was turned out of position. Although performance under the new procedure was slightly better at all delays, the differences were not reliable. In addition, a reexamination of the procedures used in these two studies indicated that turning the display may have been associated with the end of trial sequence.

View, no-view performance. I...