![]()

Part 1

The Good Old Days

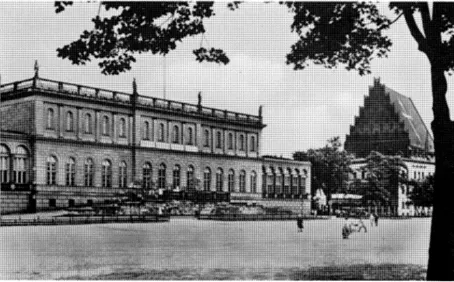

Above:

My birthplace: the house on the right, in front of the church. To its left is the King’s Palace

![]()

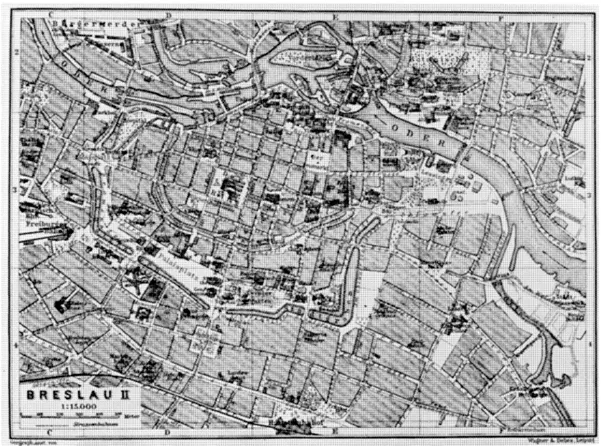

The house in which I was born, Wallstrasse 8 in Breslau,* was in a rather special situation. On the left, if you looked out of the front windows, was the big women’s prison, a bleak, ugly building; later it was pulled down and replaced by a modern block of shops. On the right, adjoining our small garden, which contained hardly any lawn but some tall chestnut trees, was a ‘café-restaurant’, with a similar but larger garden, filled with tables and chairs, which in the afternoon were occupied by elderly ladies enjoying a chat and a cup of coffee with plenty of cake. Then came the royal palace, a big and stately, but extremely plain building. The opposite side of the street was not built up; it was taken up by the Exerzierplatz, the parade-ground of the garrison, mainly of the 11th Infantry Regiment, which enjoyed a special fame for heroism from the war of 1870/71. The view from our windows was onto the vast extension of this military ground, bordered on the opposite side by the ‘Promenade’, with a double row of magnificent chestnut and lime trees. Above these you could see the roofs of the red-brick law courts, the synagogue, and in the distance the cupola of the Arts Museum. In this way my first impressions of the external world were saturated by things typically Prussian; the royal palace, the prison, the courts, soldiers practising the goose-step from morning to night, and in the distance the temples of the Jews and of the arts.

Breslau was still a fortress during the Napoleonic wars; but after Waterloo the walls were pulled down and transformed into the ‘Promenade’ already mentioned, a narrow strip of lawn and walks under beautiful trees. It widened to little parks, on small hillocks, wherever one of the old bastions had been. One of these, the Liebichshöhe, was crowned by another café-restaurant and a tower, commanding a lovely view over the town. The most beautiful spot was the Holtei-Höhe (named after the local poet Holtei, who wrote mainly in the Silesian dialect), just in the eastern corner where the old fortifications surrounding the city in a semicircle met the Oder river; from the top of this little hill you had a marvellous view, across the wide river, of the oldest parts of the city, built on two islands, the Kreuzinsel and the Dominsel, a maze of old buildings, roofs and towers, partly in the typical Silesian red-brick Gothic, including the Kreuzkirche and the cathedral, partly in the noble Silesian baroque, such as the archbishop’s palace. We children loved this view. It is impressed in my soul deeper than anything else I have seen since. But when I returned to Breslau in 1937, by then under the Nazi régime, for one day in order to visit my old aunt, Gertrud Schäfer, I was disappointed in some way: the grand view was there still, lovely and romantic as ever, but it had shrunk in size. The Holtei-Höhe was hardly more than a molehill, the river rather narrow and the towers small, compared with the image which my mind had preserved from the days of my childhood.

The Promenade, over its whole extent around the inner city, ran alongside the Stadtgraben, the moat of the old fortress. Parts of it formed little lakes where you could hire boats in summer; and in the winter it was the most splendid skating-rink. For two or even three months the ice was thick enough to skate on, and the whole population would enjoy the sport, day and night; yes, even at night, when the ice was illuminated by colourful Chinese lanterns and a band played on a wooden platform, on which a red-hot iron stove was placed to protect the musicians from freezing to death. It was on the ice that my father and mother used to meet when they were engaged. And my own first love-affair is also inseparable from the ice, which offered the most natural meeting-place for young people in a period when there were still many ‘Victorian’ or ‘Wilhelminian’ prejudices restricting the movements of well-bred youth.

In the nineteenth century the city had grown far beyond the ring of the old fortress walls. Modern suburbs stretched in all directions. But the inner city preserved much of its ancient beauty, as in many other German towns. I never quite understand why the British have sacrificed so much of their architectural heritage, which they once certainly possessed, to ugly utilitarianism.

Our house belonged to my grandfather Kauffmann. He was a great textile industrialist and owned several houses, mostly apartment houses in not very attractive districts. The Wallstrasse house was of a better type and well situated. It had only two flats of which we occupied the lower one. My father was not a rich man, a young lecturer at the medical faculty of the University, with a small salary. The Kauffmann family did not accept him without some opposition, but once my mother had got her way, it was considered necessary to fit the young couple up in a way worthy of the wealth and importance of great merchants. This was accomplished with the help of our nice flat, filled with rather pompous and heavy furniture of the ‘Victorian’ type. The house of my grandparents, in the Tauentzienplatz, was only five minutes’ walk away.

Oddly enough, I remember the names of the people who occupied the flat above us. The first tenant was a titled old lady, a Countess von Rothkirch, with her elderly daughter. At that time one of the most popular novelists was Gustav Freytag; my grandmother Born told me many a time that she knew him well as a child when they lived in the same little town (Kreuzburg). Freytag’s most popular novel, Soll und Haben, is set in Breslau and the surrounding country, and the principal figures were based on real people: the princely merchant Schröter of the novel on the former head of the well-known Silesian firm of Molinari (an Italian word meaning miller = Müller or Schröter), and the von Rothsattel family on an actual family called von Rothkirch. The old lady living in our house belonged to this clan, so my father assured me. When I re-read Soll und Haben I could not but marvel at the boundless admiration which was given to it in the circle of our Jewish families, for it is violently anti-semitic and emerges today as one of the roots of the Nazi catastrophe. I shall be returning to this point later on.

When the old Countess died, a Jewish family called Kolker occupied the flat; they had some boys about our age, but we did not take to them, and our only relations consisted of more often than not rough encounters in the garden.

My mother died when I was only four years old. I do not think that I have any direct recollection of her; the image of her which I carry in my soul is very likely the product of what I have learned about her from my father and other relatives, together with pictures and photos, and last but not least by her living image, my sister. I am sure that the lovely features and the character of mother and daughter were similar to an astonishing degree. But my mother was, according to all accounts, more brilliant. She was very musical, an excellent pianist. Young ladies of that period used to have ‘Poesie-Albums’, little books in which they asked their friends to write a few lines, a poem or sentimental quotation. I possess my mother’s album, which contains few poems, but very many musical entries, and not only from ‘ordinary’ friends but from a great many famous musicians, among them Sarasate, Joachim, Brahms, Clara Schumann, Max Bruch (who was at one time conductor of the Breslau Symphony Orchestra), and several of the celebrated Wagner singers from Bayreuth. Brahms, for instance, wrote a few lines of his Academic Festival Overture, which was first performed in Breslau when he received an honorary doctor’s degree from the University. Many artists who gave concerts in our town stayed at my grandfather’s house and my mother, who alone of the three daughters was musical, did not waste this opportunity. There is very little else I know about her. She must have been exceedingly charming and graceful. But shortly after her marriage she began to suffer from gall-stones and she died when she was pregnant with her third child. At that time the operation which saved me a few years ago from a similar fate had not been invented. But as I have had plenty of gall colic, I know how she must have suffered.

My sister and I were then left to the care of servants. The first one I remember is my little sister’s wet-nurse, a Polish woman named Valeska. There is still in my mind a faint image of this sweet and kind creature, in the colourful costume of Polish peasant women. She was a faithful Catholic and taught us the word ‘God’ and the Lord’s prayer, and whatever her simple mind knew. Most children’s nurses and maids in Breslau’s well-to-do families were Polish at that time, and this fact was so deeply embedded in my mind that the word ‘Pole’ was almost synonymous with servant girl; and when later I first met an educated Pole, proud of his nationality, it gave me a kind of shock.

Then came Fräulein Weissenborn, an elderly spinster who took care of the household and our education until my father’s second marriage. I still remember that at her first appearance my sister and I thought it extremely funny that the second half of her name was identical with our own. She was kind enough, but rather pedantic and dull, and a substitute for a mother only with respect to the material side of life. There was never anybody with whom we children could take refuge with our little sorrows and joys, as other children did with their mothers. This made us all the closer. We shared our games and play, and we developed a kind of private language, distorted expressions for everything, with which we could converse in the presence of grown-ups without being understood.

I suppose my father suffered not a little from Fräulein Weissenborn’s loquacity, which she gave full rein to at dinner and supper. There is a German proverb, ‘Nichts ist schwerer zu ertragen, als eine Reihe von guten Tagen’ (there is nothing harder to bear than a series of good days on end). Now Fräulein Weissenborn had been lady companion to an old Frau Guttentag, who was pushed about in a bath-chair; and whenever we met her on our walks with Fräulein Weissenborn on the Promenade, she entertained my father at supper with endless accounts of the old lady and all her relatives, until the sufferer once deeply offended her by interrupting her with the words: ‘Nichts ist schwerer zu ertragen, als eine Reihe von Guttentagen.’ I remember very little of these early years. We rather kept to ourselves, and our only society was our cousins; and we were never out of range of one of the Fräuleins, either our own or that of our cousins. Behind our house was a rather picturesque courtyard, surrounded by old buildings in traditional timber framework, one of which was an elementary school. From our kitchen window my sister Käthe and I used to watch the hordes of children playing in the courtyard during break and after school, and to envy their freedom of movement. We spent long hours watching the drilling and parading soldiers from the front windows, and we invented nicknames for the officers and N.C.O.s, who behaved in a particularly grotesque way. But there were also great events on the parade-ground: every year the military celebration of the king-emperor’s birthday, when a battery of the 6th Artillery Regiment fired a thundering salute just in front of our house; and occasionally even bigger parades, when the emperor visited the city and stayed for a few days in his palace, as our ‘neighbour’. The biggest event of this kind was the Three Emperors’ Conference: Wilhelm II of Germany, Franz Joseph I of Austria, and Nicholas II of Russia. We children did not know at that time the political significance of it—and I confess that I cannot remember it now; it was some last attempt to keep Russia from sliding slowly into the anti-German entente. We took it as a marvellous spectacle which we could comfortably watch from our windows, while other people had to pay considerable sums for such opportunities at hired windows or the wooden grandstands erected around the ground. There was, of course, always a crowd of uncles, aunts, cousins and friends in our rooms on such occasions, and there was a lot of fun.

We were certainly rather spoilt children. Grandmother Kauffmann was a small, but extremely brisk lady, who governed her husband partly by her energy and partly by her poor health. My father at least did not take her frequent complaints very seriously; this we found out in later years when we began to understand the rather delicate relation between the Kauffmann and Born houses. After our mother’s death, grandmother Kauffmann took over supreme command, Fräulein Weissenborn acting as her lieutenant. There was hardly a day that her carriage did not stop at our door and she looked in, accompanied by Fräulein Wedekind, her lady companion, a charming, very musical and pretty woman, with an incredibly thin waist, always dressed in the most modern style, and full of life and fun. Grandmother exercised a strict control over all our doings and supervised our health with particular care, though I think with very little medical knowledge. There were frequent clashes with my father about such questions. Later he told us how furious he sometimes was when ‘those womenfolk’ countermanded his sound medical orders with silly popular cures. He did his best, but he was working hard in his Anatomical Institute, and came home at night too tired to argue with Fräulein, who was certainly more afraid of grandmother than of him. As he did not see us much, he was easily scared when he was told that we had a cold or some other little ailment, and in this way he did not prohibit ‘those women’ from treating us as milksops, shielding us from any ‘draught’ or strenuous exercise. But on the other hand grandmother was very loving and kind, and she always had some little present or surprise. Our birthdays were certainly glorious, with heaps of toys and sweets from the grandparents, uncles and aunts, and a children’s party. Yet I am more than doubtful whether a child who is accustomed to have every wish fulfilled, that can be done with money, is happier than one of a poorer family. One little incident has stuck in my memory which was a consequence of this spoiling, and very properly led to a shameful disappointment. My mother had, apart from two sisters, one brother who had the same name as I—though I was not called after him. My father wanted to call me Marcus, after his father, a name which my mother did not like, perhaps because such classical names (Julius, Hector, Marcus, etc.) and Teutonic names as well (Siegfried, Siegmund, Gunther), were the fashion in Jewish families and became indeed specifically ‘Jewish’. So Max was considered as a ‘condensed’ form of Marcus and chosen as a compromise. Well, there was this Uncle Max, a nice, sturdy little man with a beautiful wife about whom I shall have more to say later. One day the door of our nursery was ajar when grandmother was discussing things with Fräulein Weissenborn and Fräulein Wedekind in the drawing room. Suddenly I heard the latter say: ‘I got the couple of love-birds yesterday for Max, I hope he will like them.’ Now my birthday is shortly before Christmas, and I wanted passionately to have such a pair of little parrots; but my father, afraid of the noise and smell, objected to it. So grandmother had overcome his will—how marvellous! I looked forward to the morning of my birthday with greater expectation and excitement than ever before. But when I saw the table with the presents, wonderful toys and books, cakes and sweets, but no love-birds, I broke into quiet crying, and nobody could understand it. Then I waited for grandmother’s appearance, hoping she would bring the birds; but again a disappointment and a new outbreak of tears instead of joy about the presents. At last Fräulein Wedekind, clever and kind, took me into a corner and succeeded in getting the words out of me: ‘But you said the other day you had got a pair of love-birds for me,’ which provoked an explosion of laughter from her and subsequently from the whole family.

When I learned that the birds were a Christmas present for Uncle Max, I was overwhelmed with shame: my eavesdropping and greed and discontent had been disclosed to the whole family, and I was the laughing-stock of all of them. The others forgot it quickly—I was not teased. But I did not forget, and it was the first experience which taught me to be reserved. Many others followed. There was no mother in whom I could confide, and who could restore my confidence. So it happened that I became a somewhat odd fellow. I did not know this myself, but after I was married and, for the first time, became intimate with another human being, I learned from my wife what was wrong with me. Well, that was twenty-five years later, and until my narrative reaches that period I shall have to refer to this point more than once. I was never deeply interested in characters and in the art of describing them, and I find it an awkward business, especially in respect of my own. But it has to be done. I shall however feel happier when I come to describe why I became interested in crystals and relativity and quantum theory.

But to return to our childhood. It might be thought that we were genuine big city children, living in apartment houses, accustomed to the traffic of busy streets and cut off from the natural life and beauty of the countryside. This is, however, not quite true. There was in the first place Kleinburg. My grandfather Kauffmann had bought a big house in a magnificent park-like garden, in the village of Kleinburg. At that time Kleinburg was still separated from the town by a strip of open country, but was already becoming transformed into a suburban agglomeration of villas, used as summer quarters by well-to-do merchants and civil servants. It was connected with the city by tram, pulled at that period by horses. During the summer months, we spent nearly every afternoon in the Kleinburg garden; sometimes the journey was made by tram, but very often in grandfather’s carriage, which collected the different groups of grandchildren, with their nurses or Fräuleins, and took them back in the evening. The garden contained an enormous expanse of lawn, a double row of old chestnut trees, a large orchard with fruit trees and vegetable beds, two hard tennis courts, a little ‘forest’ of pine trees, and a playing-ground for children with swings, ladders and other gymnastic apparatus. There were always a considerable number of children, mostly relatives: the two daughters Alice and Claire of Uncle Max Kauffmann; Hans, Lene and Grete Schäfer, the children of my mother’s sister Gertrud, and a lot belonging to second cousins, mostly the sons and daughters of grandfather’s brothers. As the garden was well fenced in, we children were more or less left to ourselves, while our nurses sat chatting in the shade of a group of lovely trees. So we could run about and play in almost complete freedom. The only source of mischief was the fruit garden. There were stretches of it allowed to us children; but as we never could wait until the strawberries, peaches, pears, cherries and plums were really ripe, we ate plenty of them in a state when they were apt to produce indigestion. Later, when our own harvest was eaten up, there was the marvellous crop of grandfather’s own beds and trees growing under our noses, and although we certainly got our proper share, we were exposed to a temptation which led to regrettable raids and sometimes to sad consequences.

This was our little paradise. But then there was the really great paradise, the summer holidays in Tannhausen. Here I must tell you a little more about the Kauffmann family, and about the textile firm which was the core of it. The founder of this firm was my grandfather’s father, Meyer Kauffmann, a small Jewish trader in the little Silesian town of Schweidnitz. He bought textiles woven on hand-looms by poor people in the lovely valleys of the Silesian hills (Sudeten), sold them at the big fairs in Breslau, Frankfurt on the Oder and Leipzig, and supplied the home industry with raw material, wool and cotton. He was one of the firs...