![]()

1 Introduction

Understanding memory

A conceptualization of memory

Even the most cursory examination of human behaviour reveals that current activities are inescapably linked to the past. Such knowledge of the physical world, of the properties of objects and substances, of machines and animals, that a person requires for a competent and safe existence must be acquired by experience. This experience may be direct contact with the environment or it may be the communication of facts by verbal or other means, but the cumulative effects of past experiences lie at the root of knowledge. This is true also for the social environment: the acquisition of language skills and social conventions all depend on experience, as do expectations about the behaviour of members of perceived social groups. In addition to such general knowledge, how people perceive themselves – their self image – depends on placing themselves in relation to what has happened in the past and what consequently may be expected to happen in the future. Equally, in addition to such general knowledge competent behaviour requires that specific past events exert their influences in the present. For example, it is essential that there is some ‘keeping track’ of what has happened: if the completion of particular tasks were not influential on future behaviour they might be repeated again and again! And imagine the difficulties if resolutions for future actions exerted no influence when the time to act came!

These observations, while superficial, show that coping with the present and planning for the future invariably involve drawing on past experience. There must, then, be some means, internal to the individual, of bridging the gap between the past and the present. Understanding that bridging forms the basis of memory research and of this book.

The cognitive approach

The study of human memory can be approached in any of a number of ways. Interest may, for example, be concentrated on those biochemical changes in neural pathways which accompany the acquisition, retention or forgetting of material. Alternatively, the specific neural structures in the brain which are necessary for particular remembering activities may be the subject of enquiry. But while it must be accepted that certain physical processes and structures are necessary for the proper functioning of memory, the psychology of memory need not be concerned with them at all. It is possible, for example, to gain a satisfactory understanding of why a person should strive to remember the contents of a psychology course, or why he should wish not to remember a particularly unpleasant experience, without resorting to physical mechanisms.

Yet another approach to understanding memory falls within the framework of what has become generally known as cognitive psychology. This is based on the assumption that observed patterns of behaviour, together with private subjective experiences, depend on unobservable ‘mental’ events involving mental mechanisms and processes. The fundamental aim of cognitive psychology is to identify these events and to determine lawful relationships amongst them, and between them and observed behaviours. In the preceding section it was made clear that the concept of memory has a crucial role to play in understanding behaviour, both overt and covert. Thus, cognitive psychology encourages, indeed demands, specific attention to the internal representations of past experiences and their utilization in mental activities. It emphasizes the interdependence of memory and other mental processes and so provides a broad and fertile framework within which the study of memory may be undertaken.

The cognitive approach is not new. As we shall see shortly in connection with memory specifically, concern with and speculation about the nature of mental processes can be traced back to the early Greeks with continuing interest up to modern times. In the latter part of the nineteenth century it was accepted that the aim of what had recently become the independent discipline of psychology was the analysis of mental processes such as sensation, perception and imagery. To this end it was common to employ the method of introspection in which subjects reported on their own conscious mental activities. But the shortcomings of this method quickly became apparent and it did not support the study of mental events for long. The method relies on the use of trained observers and the training may well bias what is observed and what is reported. Indeed, the very act of observation may well change the processes being observed. Other shortcomings include the private nature of the observations: different observers may give different reports of the same phenomenon but there is no way of checking this because the observations are not open to public scrutiny or replication. And, of course, not all mental processes need be conscious ones.

The limitation of introspection led to a loss of interest in what may aptly be termed ‘mentalism’ and helped pave the way for the growth of behaviourism particularly in America. Behaviourists from Watson (1913) to Skinner (e.g. 1963) have maintained that behaviour should be explained without reverting to hypothetical internal mechanisms either conscious or unconscious, and no matter whether they are based on subjective reports or other sources of evidence. Such mechanisms, according to the behaviourists, cannot be observed directly, are purely speculative, and so may be deceptive. Instead, explanations must be derived in terms of observable variables, e.g. amount of reinforcement, speed of response, retention interval, and so on. Behaviourists, then, have maintained that the mental activity which may or may not accompany behaviour is unimportant to any satisfactory understanding of that behaviour.

It is now generally accepted that there are a number of fatal difficulties for classical behaviourism and its ‘empty organism’ approach. One of these difficulties stems from the fact that an identical physical stimulus may give rise to different responses on different occasions. To take a simple example imagine that you have always made a left turn at a particular road junction on your way home from college. One evening, though, having decided to visit a friend you turn right at this junction. Such a new response to an old stimulus cannot be understood without involving some internal goal or plan (see Miller, Galanter and Pribram, 1960). Likewise, the same response made to the same stimulus on different occasions may demand interpretation in terms of intentions as when striking someone is done accidentally rather than intentionally. Human behaviour is not stimulus-bound; it cannot be accounted for in terms of specific patterns of stimulus-response pairings experienced in the past. This point has been made clear by Chomsky (1959) in his attack on the behaviourist account of language behaviour (see Harris and Coltheart (1986).

While classical behaviourism has run into problems of the sort just mentioned it must not be forgotten that this approach was itself largely a response to the inadequacies of introspection and was bound to be influential so long as adequate paradigms for studying mental processes were lacking. Of course, there were those such as Freud, Piaget and Bartlett who, during the first half of this century, stressed the importance of inner processes and mechanisms for understanding behaviour. But over the last 30 years or so the cognitive approach has received a fresh impetus with the development of information-processing science and technology dealing with the internal workings of computers and other electrical and electronic systems. This area of scientific activity confirmed the reality of specific internal and directly unobservable processes capable of mapping input on to output in a variety of complex ways and consequently suggested new paradigms for the study of cognition. This new impetus to mentalism found elegant expression in a number of works including Broadbent’s (1958) Perception and Communication, Miller, Galanter and Pribram’s (1960) Plans and the Structure of Behavior, and Neisser’s (1967) Cognitive Psychology. But why should developments in cognitive psychology and in memory theory in particular apparently be dependent on developments in other spheres of science? We turn to this question now.

Theories and models

Scientific endeavour involves discovering lawful relationships amongst phenomena, i.e. finding order in nature. Throughout past centuries there have been conflicting views on the necessary manner in which this goal must be achieved and it is worth noting that much of the debate has been amongst philosophers rather than practising scientists. On the one hand there have been those who believed that scientific progress can be achieved only by the method of deduction, that is, arguing from a ‘given’ set of axioms to predict certain phenomena which are then confirmed or disconfirmed by observation. In contrast, proponents of induction have argued that the necessary scientific method involves firstly the observation of phenomena and then the formulation of laws which comprehend those phenomena. The generally accepted view now, formed notably under the influence of writers such as C.S. Pierce and K.R. Popper (see, e.g., Popper, 1959), is that in practice neither induction nor deduction is sufficient to account for scientific progress, nor indeed are the two taken together. Clearly, deduction alone is not sufficient because it provides no source of the axioms from which deductions may be made. Induction, on the other hand, provides no guide to which phenomena should be observed, nor does it give any hint as to how a start may be made in seeking order amongst any observations which are made. And, if some law which comprehends a set of observations is arrived at it is always possible to find alternative laws which also comprehend them: induction simply cannot lead to ‘truth’ with any certainty.

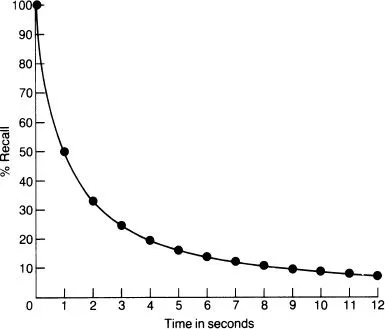

The separate limitations of induction and deduction as accounts of scientific method are not overcome merely by combining the processes – even then there are gaps to be filled. It is perhaps best to illustrate this point with a specific example. Suppose that some subjects take part in a memory experiment. On each trial they are shown a consonant trigram (e.g. BNK) for 2 seconds and then required to count backwards by threes, aloud, from a given number. After an interval of counting (t seconds), a signal indicates that they must recall the consonants in the correct order. The consonants change from trial to trial, and so does the interval of counting. (Without the counting the subjects could rehearse the consonants and presumably would recall them correctly no matter how long the retention interval!) Imagine, now, that the points in Figure 1.1 represent the average performance of the subjects, expressed as the percentage of trigrams correctly recalled (P per cent), at various retention intervals (t seconds). Familiarity with mathematical functions should suggest that performance is related to the time elapsed by the formula:

This formula, which was arrived at by induction, represents a

theory and can now be used to deduce values of P for new values of t, and these could then be confirmed or dis-confirmed by observations. So far so good. But suppose now that a new set of observations shows that the relationship

only holds good for a limited range of t values, or is restricted to specific conditions involving consonant trigrams and backward counting. The theory itself does not suggest any way in which a modification should be made to account for these new observations. And, of course, neither induction nor deduction provide any account of the motivation to make the original observations: possibly some purely practical requirement impelled the study, or perhaps the investigation was simply ‘playing games with nature’! P.B. Medawar deals with these problems in his book

Induction and Intuition in Scientific Thought (Medawar, 1969).

Figure 1.1: A fictitious forgetting curve

As the title of his book suggests, Medawar argues that intuition is an important ingredient of the scientific method: it is this which provides the source of ideas which induction and deduction, even when taken together, fail to suggest. But clearly intuition involves more than mere unaided guessing, so how are the ideas which form the starting point of the deductive process, or which suggest modifications of disconfirmed ideas, arrived at? As Braithwaite (1962) points out, very often an appeal is made to some area of nature where phenomena have been successfully understood, i.e. lawfully related. The laws from this area of science are then used as analogies for the laws governing those phenomena for which an understanding is sought. Braithwaite refers to such analogies by the term as if models, using the term model rather than theory when the range of phenomena which may be so understood is small. He argues that their use involves the assumption that the phenomena of interest are related as if they were produced by some principle or set of principles which are already understood. Thus early attempts to understand optics were based on the notion that light behaved as if it were wave-like (understood from investigations of liquids) or corpuscular (i.e. small particles having characteristics derived from the behaviour of large spherical objects). As if models, then, provide ideas, hypotheses, axioms, from which the deductive process may proceed, and supply ways in which theories or models may be modified in the light of further observations. Such models, Braithwaite insists, are an important ingredient of most scientific thinking.

Models of memory

That familiar, concrete mechanisms of technology can provide useful as if models for understanding the nature of ‘mind’ has been recognized at least as long ago as Hippocrates who lived from 460–375 BC (see Marshall, 1977). Later Thomas Reid (1719–96) stated in his Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man that it is ‘very natural to express the operations of the mind by images taken from things material’. This is certainly apparent in the development of models of memory. One of the earliest documented as if models of memory was that of Plato who likened the properties of human memory to those of wax tablets. Sensory images, he suggested, leave impressions on the mind just as a signet ring may leave an impression on wax: the persistence of the impressions is analogous to remembering while fading or effacement is analogous to forgetting. The wax tablet analogy survived over many centuries being utilized by, for example, Gratoroli in the sixteenth century, Harris in the eighteenth century, and William James at the turn of this century. Apart from the rather obvious analogy between the persistence and fading of impressions with retention and forgetting of memories the wax tablet model has other attractive features. For example, certain individual differences in memory ability can be understood in terms of the size of the wax tablet determining how many impressions can be retained, and the consistency of the wax determining the ease with which impressions can be made and their durability. According to several versions of this model recognition of an object or person as familiar, i.e. having been seen before, takes place by a process analogous to matching the current sensory image against an impression on the wax. Failure to find a matching impression leads to the experience of unfamiliarity. But, as Plato acknowledged, this model has a major shortcoming in that it provides no mechanism for recalling rather than recognizing what is in memory. To deal with this problem he resorted to another as if model based on an aviary. According to this model learning involves capturing ideas (birds) in memory (the cage), and recall involves retrieving particular birds from the cage. The model suggests that failure to recall does not necessarily mean that the required memory is not present but possibly that capturing it is difficult. Furthermore, just as similar birds flock together so do similar ideas and related memories may be erroneously recalled because of their proximity to the sought-after memory.

In the eighteenth century David Hartley (1705–57) capitalized on Isaac Newton’s work on energy and motion to propose that memories are retained by the vibration of medullary particles. The activity of these particles, he proposed, is increased by sensory activation and gradually decays as energy is dissipated. (It is interesting to note that Hartley’s model is remarkably similar to at least one recent model of word perception (Morton, 1969).) In the next century a number of writers drew on analogies with chemistry. Jules Luys (1829–95) turned to phosphorescence, the continuing luminosity of certain materials after the source of light has been removed, to make a simple analogy while John Stuart Mill (1806–73) proposed a more complex model based on ‘mental chemistry’. One attractive feature of this latter model is its recognition of the dynamic nature of memory: just as chemical compounds (such as water) are quite different from the elements of which they are composed (hydrogen and oxygen), so the fusing of sensory elements creates new mental entities which are more than the sum of the parts. Later still, the property of photographic plates of responding to and retaining optical details was taken as the basis of memory models. Yet more recently both weathered signposts (Brown, 1964), electrical condensers (Shephard, 1961) and the hologram (Chopping, 1968; Eich, 1982) have provided as if models.

Among recent analogies those involving information processing systems, especially the electronic computer, have provided perhaps the most successful as if models of cognition broadly and of memory in particular. Indeed, so effective has been the exploitation of the computer analogy that the term ‘cognitive psychology’ is often taken to mean the modelling of mental processes based on such devices rather than in the sense of a general concern with mental events.

A basic computer incorporates an input system, a central processor, memory, and output generator. Typewriter keyboards, magnetic tapes, card readers, or even speech recognition devices may provide sources of input. But whatever the initial nature of the input it must be converted or coded into a form which the central processor can utilize. Once this has been done the information contained in the input can be operated on by the central processor according to the instructions already stored in the system as a whole. The results of these operations can then be recoded and used to provide output via typewriters or visual display units, or to control mechanical devices. It is also possible that the instructions stored in the compu...