![]()

Suicidal Rebellions and the Moral Hazard of Humanitarian Intervention

Alan J. Kuperman

In the 1990s a burst of ethnic violence and the end of the Cold War gave rise to an emerging norm of humanitarian military intervention (Wheeler, 2004). US President Bill Clinton (1999) enunciated this doctrine clearly: “If the world community has the power to stop it, we ought to stop genocide and ethnic cleansing”. Two years later the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (2001; Shue, 2004) went further by declaring a ‘Responsibility to Protect’, suggesting that failure to intervene by those capable of doing so would actually violate international law. More recently, in December 2004, a high-level UN panel reiterated: “We endorse the emerging norm that there is a collective international responsibility to protect, exercisable by the Security Council authorizing military intervention as a last resort, in the event of genocide and other large-scale killing, ethnic cleansing or serious violations of international humanitarian law” (United Nations, 2004).

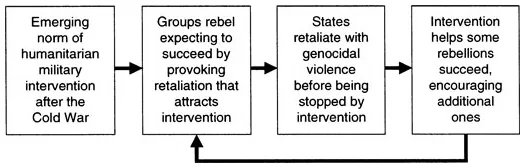

The common wisdom underlying this emerging norm is that humanitarian military intervention reduces the amount of genocide and ethnic cleansing (forced migration), which together can be labelled ‘genocidal violence’. However, this causal relationship has not been demonstrated, and there is some contrary empirical evidence and deductive logic suggesting that the intervention norm may at times actually cause genocidal violence. This is because the norm, intended as a type of insurance policy against genocidal violence, exhibits the pathology of all insurance systems by creating moral hazard that encourages risk-taking (see Figure 1). Specifically it encourages disgruntled sub-state groups to rebel because they expect intervention to protect them from genocidal retaliation by the state. Actual intervention, however, is often too late or feeble to prevent such retaliation. Thus, the norm causes some genocidal violence that otherwise would not occur. This chapter develops a theoretical framework to understand the problem; illustrates it in two cases; discusses analogous problems in economics; analyses potential remedies; and concludes by exploring the putative moral responsibility to intervene.

Figure 1. Moral hazard of humanitarian intervention and its potential consequences

The Empirical Puzzle: Victim Groups Provoke Retaliation

The starting point for this exploration is a surprising, yet largely unexplored, empirical puzzle in the literature: most cases of genocidal violence arise when ethnic rebellions provoke massive state retaliation. (‘Provoke’ means to cause a reaction, whether intentionally or not.)1 In other words, unlike in the prototypical case of genocide—the Nazi Holocaust against the Jews— most ethnic groups that fall victim to genocidal violence are responsible for initially militarizing the conflict. The obvious question is why would members of an ethnic group, which is sufficiently vulnerable to fall victim to genocidal violence at the hands of the state, provoke that very outcome by launching a suicidal rebellion against the state’s authority? The puzzle is even more curious because the state typically issues advance warning to the ethnic group that it will respond to any such rebellion with massive retaliation.

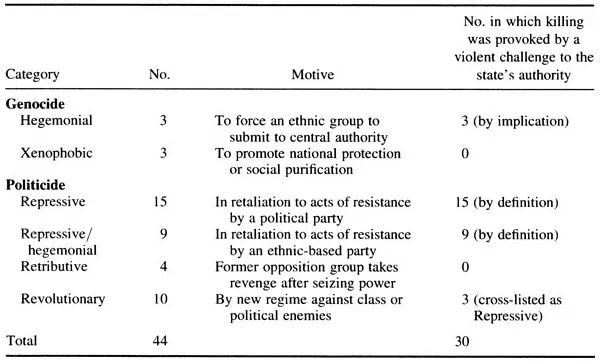

Although counter-intuitive and little publicized, the finding that genocidal violence is usually provoked by members of the victim group is robust in the literature, across varying definitions, methodologies and timeframes within the post-World War II era, which is the only period for which reliable data are available. From 1943 to 1987 Harff and Gurr (1988) identify 44 episodes of ‘genocide and politicide’, defined as state-sponsored policies lasting for at least six months that deliberately kill thousands of non-combatants because of their identity or political affiliation, respectively (see Table 1).2 They further divide the cases into six categories based on the motive of the perpetrator: hegemonic genocides aimed at forcing ethnic groups “to submit to central authority”; xenophobic genocides to promote “national protection or social purification”; repressive politicides in retaliation to “oppositional activity” by political parties; repressive/hegemonic politicides also in retaliation to “oppositional activity” but in cases where the opposition party is ethnically based; retributive politicides by former opposition groups after seizing power to take revenge against former ruling groups; and revolutionary politicides by new regimes against “class or political enemies”.

Table 1. Harff and Gurr’s 44 cases of genocide and politicide from 1943 to 1987

Harff and Gurr categorize 24 of the 44 cases (55%) as repressive or repressive/hegemonial, stating explicitly that the victim group “provokes this kind of mass murder” by “acts of resistance”. Three other cases are categorized as hegemonial, which is closely related because the state’s violence aims to force a communal group “to submit to central authority”, which presupposes that the group is already resisting state authority. In addition, according to Harff and Gurr, three more cases tabulated as revolutionary can be categorized as repressive as well. Thus, based on Harff and Gurr’s coding, at least 30 of the 44 cases (68%) exhibit the phenomenon in which rebels provoke their own group’s demise by violently challenging the state’s authority.3

In a separate research project Helen Fein (1990) focuses exclusively on genocide, ostensibly excluding cases of pure politicide in which victims did not share common ethnicity and were targeted solely for political reasons. This confines her database for the period 1945–88 to 19 cases, which she divides into four categories, also based on the motive of the perpetrator.4 She uses different labels for categories that are quite similar to those of Harff and Gurr: their repressive category translates roughly into Fein’s ‘retributive’; revolutionary becomes ‘ideological’; xenophobic becomes ‘developmental’; and hegemonial becomes ‘despotic’. Despite this semantic difference, Fein likewise finds that genocide is usually provoked by members of a group challenging the state: “one could classify at least 11 cases [58%] as retributive genocide in which the perpetrators retaliated to a real or perceived threat by the victim to the structure of domination”. She also suggests that two of the other cases could be coded properly as retributive, which would raise the proportion in her database to 68% as well.5

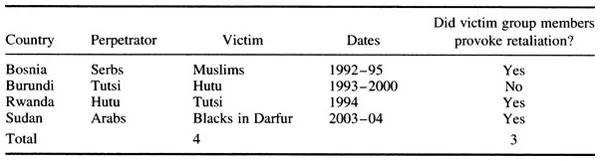

For the post-cold war period I have compiled a database of large-scale, intrastate genocidal violence that has broken out since 1990, in which at least 50 000 non-combatants from an ethnic or political group were deliberately killed during a period in which at least 5000 were killed each year.6 This comprises brief but intense campaigns, as well as sustained but less intense campaigns. It includes extermination campaigns that directly target civilians, war strategies that knowingly inflict collateral damage, and economic blockades or episodes of ethnic cleansing that cause starvation and disease. However, it intentionally excludes cases of protracted low-level civilian killing typically arising from guerrilla or counter-insurgency campaigns, on the grounds that such violence is a qualitatively different phenomenon. It also avoids lumping together as a single case multiple incidents of midlevel violence that are separated by significant periods of relative calm.7

Based on available evidence, four cases from 1990–2004 clearly satisfy the definition above, as listed in Table 2.8 Three of the four cases (75%)—Bosnia, Rwanda and Sudan (Darfur)—fit the pattern in which members of the victim group provoked the group’s demise by violently rebelling. Burundi does not fit, because the ruling Tutsi perpetrated genocidal violence in response to a peaceful challenge to their authority, the election of the state’s first Hutu president in 1993, rather than to a violent rebellion.9

Table 2. Outbreaks of large-scale genocidal violence (including politicide) since 1990

Note: Nine other putative cases cannot yet be included because available evidence does not permit a determination that a sufficient number of civilians of any group was killed deliberately. These cases are Afghanistan, Algeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq (vs Shiites), Liberia, North Korea, Russia (vs Chechens), Rwanda (vs Hutu) and Sierra Leone. In addition, three cases of genocidal violence during this period are excluded because they started before 1990: Angola, Somalia and Sudan (vs southerners).

The ‘Rationality’ of Genocidal Violence

Building on the literature’s finding that most genocidal violence is provoked, many theorists agree that states act ‘rationally’ when they respond to such challenges with genocidal violence. (‘Rational’ action attempts to maximize one’s interests based on available information and expectations.) Far from the popular caricature of genocidal violence as a psychopathic outburst, these theorists typically view such violence as a calculated action by the state to defend its power against an aggressive challenger. As Barbara Harff (1987) writes, “usually genocide is the conscious choice of policymakers … for repressing (eliminating) opposition”. Helen Fein (1979) long ago noted that “to grasp the origins of modem premeditated genocide, we must first recognize … how it may be motivated or appear as a rational choice to the perpetrator”. More recently, and more simply, Fein (1994) has concluded that genocide “is usually a rational act”. Likewise, Roger W. Smith (1987) characterizes genocide as “a rational instrument to achieve an end”. Peter du Preez (1994) says that genocidal violence is usually “perfectly rational” and even “pragmatic”, because the state chooses this policy when “it is thought that mere military victory will not solve the problem and measures of ‘population adjustment’ are necessary”.10 Matthew Krain (1997) offers a similar rational explanation for state-sponsored mass murder: “elites trying to hold onto power can and must reconsolidate power quickly and efficiently”. Going beyond these earlier theorists, who acknowledge but do not focus their scholarship on rational incentives, Benjamin Valentino (2000) emphasizes such perpetrator calculations and motivations as the core of his new “strategic” theory of “mass killing”.

It is important to underscore that when theorists assert that a state pursues genocidal violence as a rational choice, it is not necessarily the optimal choice nor a moral one. When confronting rebellion, state leaders cannot be certain of the consequences of any policy alternative; in the absence of perfect information, rational action may be suboptimal.11 Several policies may appear capable of achieving the interests of state leaders: offering concessions; pursuing counter-insurgency against armed elements; compelling forced migration; or attempting extermination. Nor is there yet conclusive case-study evidence that states typically do act rationally in this situation. Further research is needed to determine when and why states respond to rebellion with genocidal violence.

No Good Explanation of Suicidal Rebellions

In remarkable contrast to the chorus of rational explanations for perpetrator behaviour, there is no explicit rational theory to explain suicidal rebellions. Instead, theorists of genocidal violence imply that such rebellions are an all but inevitable response by vulnerable societal groups to long-term discrimination or oppression at the hands of the state. The literature thus harbours an implicit, non-rational theory for the phenomenon: vulnerable groups are driven by the frustration of prolonged discrimination to launch violent challenges against state authorities without necessarily calculating their chances of success or the consequences of failure, and thereby unwittingly provoke their own demise.

For example, Fein (1990) states that: “Domination by a ruling ethnoclass … lead[s] to violent rebellion by the dominated class … [provoking] expulsion and genocide”. Likewise, Harff and Gurr (1989) write: “One tell-tale manifestation of conflicts with genocidal potential is discriminatory treatment of ethnic, religious, national, and regional minorities by dominant groups … [Minorities] resisting discriminatory treatment are more likely to encounter massive state violence than quiescent groups.” Despite the obvious risks of retaliation, say Harff and Gurr, discriminated groups pursue violent resistance because “leaders have alternatives, victims rarely do”. But, in reality, discriminated groups almost always do have alternatives to violent resistance, which could enhance their welfare by reducing significantly their risk of suffering genocidal violence. The fact that Harff and Gurr view rebellion as all but inevitable, despite the availability of obvious, welfare-improving, alternative strategies, implies that they view subordinate group actions as irrational.

This implicit theory from the literature is depicted graphically by the bold arrows in Figure 2. Although it may account for much genocidal violence, it is under-specified at every juncture. First, the literature does not explain when and why states are dominated by certain groups that discriminate against others. Second, even if suffering discrimination were a necessary condition for a violent challenge against the state, which empirically is not true, such discrimination is clearly insufficient by itself because most groups suffering discrimination do not launch such challenges.12 Third, although genocidal violence may sometimes be a rational response by a state to such challenges, in other cases it may be equally or more rational for the state to concede to the demands of the challenging group, or to combat the challenge with a disciplined counter-insurgency aimed only at militants rather than at civilians. Thus the implicit theory is contingent at every turn on other factors (‘condition var...