- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Conquest of Assyria tells what must surely be one of the most romantic tales of archaeological endeavour. The great cities and ancient palaces of Mesopotamia had lain buried for over two millenia, and were all but forgotten, half remembered in the Hebrew Bible and Classical texts. This volume records the dramatic finds, the decipherment of the cuneiform system of writing and the rediscovery of a lost civilisation.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

Ciencias socialesSubtopic

ArqueologíaPART I

THE FIRST EXPLORERS

CHAPTER ONE

THE MOUNDS OF NINEVEH

On a sweltering day in June 1842 two riders arrived at the gates of Mosul, a provincial town in the Ottoman empire. They came from Baghdad in the south and had taken the customary road that led them through the fertile country east of the Tigris; they reached Mosul itself by crossing a rickety bridge of boats which connected the town on the western bank with the villages across the Tigris. One of the men was a Turkish post-rider, a ‘tatar’, who was on his way to Constantinople more than 2,000 km away with official imperial mail. The other was a young man dressed as a Bakhtiyari, a tribe that lived in Khuzistan, the mountainous south-western corner of Iran. A more observant eye would soon decide that he was a European, however, and indeed, after having parted from his travel companion, who entered the local Pasha’s palace on the river, he went straight to the British Vice-Consulate where he was received as an old friend. He was the twenty-five-year-old British adventurer Austen Henry Layard.

The same day he was introduced to the new French consul in Mosul, the forty-year-old Paul Émile Botta and the meeting between these two men had a very special significance, for it may be said to mark the beginning of the archaeological exploration of ancient Mesopotamia. Botta and Layard were destined to become the discoverers of ancient Assyria.

Mosul was a somewhat unlikely place to meet. Like most of the Near Eastern towns of the time it was a sleepy and shabby place, and in spite of a glorious past it was now reduced to rubble and decay after decades of neglect and misrule, with large parts of the town in ruins (see Figure 1.1). It was the seat of a Pasha, or provincial governor, appointed by the Turkish government at Constantinople, and he ruled over a mixed population of Muslim and Christian Arabs and the Kurds in the mountains. A contemporary traveller described the town in the following words:

Mosul is an ill-constructed mud-built town, rising above the banks of the Tigris, and backed by low hills; in the centre is a tall brown ugly minaret, very much out of the perpendicular; the interior of some of the houses is faced with a translucent stone, called Mosul marble…. Part of the old Saracen walls still remain: they are very massive… the ground between the walls and town is occupied by stagnant pools, ruins and dead bodies of camels and cattle, which is enough to breed a pestilence; the bazaars are mean and dirty.(Mitford 1884: I, 280)

Figure 1.1 The decrepit centre of Mosul, seen from the ruins of Nineveh on the eastern bank of the Tigris. Engraving by E. Flandin, the artist who worked with Botta at Khorsabad. (From Flandin 1853–76: Plate 30)

Not a nice place to spend the summer, or for that matter any other time of the year. The summers here are marked by a heat that quickly becomes unbearable and which scorches the landscape so that all one sees is a bone-dry, brown steppe; the winters, on the other hand, can be very cold, and violent rainstorms turn all roads and streets into slippery, muddy quagmires. Only the brief spring season turns this land into a paradise, where shoulder-high forests of flowers explode in incomparable colours, while clouds of butterflies slowly glide over the fields.

One hundred and fifty years ago most of the Near East was under Turkish control. The countries were governed from Constantinople where the Sultan, the ‘Sublime Porte’, sat as the sovereign of a realm which was in rapid decay. It was the ‘Sick Man of Europe’, and the great powers – England, France and Russia – were already in conflict over which attitude to adopt towards the tottering Ottoman Empire. The Russian Czar saw his interest in the collapse of the Turkish state so that he could divide the remains with England, whereas the British government had a somewhat unclear policy, which, however, tended to support the authority of the Sultan and his attempts to keep the vast empire intact.

Not many Europeans found their way to Mosul. A couple of British merchants regularly stayed here trying to conduct some trade in weapons or cloth, knives and scissors. There was an English Vice-Consul here, a local Christian Arab called Christian Rassam who was married to an English lady, Matilda Badger Rassam; her brother was a missionary who had lived in the town earlier and who occasionally passed through. One might also meet a somewhat eccentric English doctor and geologist, Ainsworth, who had settled here after having taken part in a naval exploration of the river Euphrates a few years before (Ainsworth 1888; Chesney 1850). He had been sent out on a new assignment by the Royal Geographical Society and the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge. There were two distinct groups of missionaries: American Presbyterians and a group of Italian Dominican monks led from Baghdad by an intense man called Valerga. These last kept apart from the other Europeans, and especially from the British, who were regarded by them as dangerous heretics (Fletcher 1850). What led Botta and Layard to this God-forsaken place?

Their meeting was accidental, neither of them knew the other before they met in Mosul, but it turned out they had common interests. Layard was on his way to Constantinople carrying official British mail, but since his companion had business to conduct with the Pasha they had to stay in the town a few days. This gave Layard the opportunity to meet Botta, who was the recently appointed French consul at Mosul.

They were not really interested in Mosul but looked with fascination on the mounds that were located across the river on the eastern bank of the Tigris. A series of enormous ramparts or walls encircle a rectangular area of some kilometres’ length and breadth, and in this enclosure lay a couple of large mounds.

Local people called the whole area ‘Nuniya’, and it was believed to be the location of the ancient Assyrian capital city of Nineveh. Today this name probably means little to most people, but in the nineteenth century it would resonate in the mind of any reasonably educated European, who would know the stories about this city from the Old Testament and from a series of legends told by classical authors. Nineveh had been the centre of one of the largest and most important empires in the ancient world, one whose power according to tradition had covered the entire Near East, including Palestine and Egypt. It was also, however, an empire which had left no concrete traces behind at all. Assyria had disappeared, leaving nothing but myths and legends.

Except that there were these vast mounds close to Mosul, which, according to local legend, covered the ruins of the ancient city. This tradition had actually been known by the learned of Europe, those few who had heard of the place, but it had never been information which had been seen as particularly important or interesting.

Layard had already seen the mounds a couple of years previously, when he had been on his way south towards Baghdad, and he had been ‘deeply moved by their desolate and solitary grandeur’. In his Autobiography he describes this first visit:

The site was covered with grass and flowers, and the enclosure, formed by the long line of mounds which marked the ancient walls of the city, afforded pasture to the flocks of a few poor Arabs who had pitched their black tents within it. There was at that time nothing to indicate the existence of the splendid remains of Assyrian palaces which were covered by the heaps of earth and rubbish. It was believed that the great edifices and monuments which had rendered Nineveh one of the most famous and magnificent cities of the ancient world had perished with her people, and like them had left no wreck behind. But even then, as I wandered over and amongst these vast mounds, I was convinced that they must cover some vestiges of the great capital, and I felt an intense longing to dig into them.(Layard 1903: 306–7)

He now revisited Nineveh in Botta’s company, and he heard with jealous excitement that the Frenchman had been placed in Mosul for the purpose of opening excavations of the ancient city.

The two men wandered about on the great mounds, took measurements and engaged in speculations. What was hiding in the ground under their feet? Was this really the Nineveh mentioned in the Old Testament? There the city appears as the mighty capital of the Assyrians, from which their empire was governed, home to kings like Tiglath-pileser, Shalmaneser, Sennacherib and Esarhaddon. In the Book of Jonah we hear that Nineveh ‘even to God’ was a large city, covering a distance of three days’ journey, and God estimated the population of this metropolis as ‘more than twelve times 10,000 people, who are unable to distinguish right from left, and much cattle’.

As the capital of the Assyrians who plagued Judah and Israel, Nineveh was naturally not mentioned in a positive light in the Jewish Bible; the Prophet Nahum sings a glowingly hateful hymn of ecstatic joy over the final destruction of Nineveh:

Ah! blood-stained city, steeped in deceit,

full of pillage, never empty of prey!

Hark to the crack of the whip,

the rattle of wheels and stamping of horses,

bounding chariots, chargers rearing,

swords gleaming, flash of spears!

The dead are past counting, their bodies lie in heaps,

corpses innumerable, men stumbling over corpses –

(Nahum 3: 1–3)

Many other passages in the Old Testament express the same fathomless hatred of the Assyrians and their enormous capital, for it was from here that the endless campaigns started that eventually crushed Israel and sent the Jews in exile to other provinces in the Assyrian empire. Naturally Assyria, like Babylon, was in the end struck down by God, but only after both countries had inflicted incomprehensible destruction and misery on the Jews and other peoples of the Near East.

Like all reasonably well-educated Europeans, Botta and Layard knew their Bible and the Greek and Roman classics. They were aware that the very first account of the Assyrian ruins was given by the Greek general Xenophon who led 10,000 mercenaries to Babylonia and back in the years 401–400 BCE. His army camped one night on their return journey close by the Tigris on a ruin he calls ‘Larissa’ – which must be the mound now known as Nimrud, a place that occupies a central role in this book. Xenophon thought that this ‘large deserted city’ had been built by the Medes, an Iranian people. The following day the army reached another ruin which Xenophon described as ‘a large undefended fortification near a city called Mespila’. This name must be a strange version of ‘Mosul’, and the ruins he described must be the same ones which so occupied Botta and Layard. Xenophon wrote:

The base of this fortification was made of polished stone in which there were many shells. It was fifty feet broad and fifty feet high. On top of it was built a brick wall fifty feet in breadth and a hundred feet high. The perimeter of the fortification was eighteen miles.(Xenophon 1979: 162–3

Xenophon can give this dry, factual description, but he does not even know the name of the site. Yet he was here only two hundred years after the fall of Nineveh, which happened in 612 BCE when a combined force of Medes and Babylonians stormed its walls and destroyed the city; it appears that in the short span of time Nineveh had been forgotten and that, although the ruins themselves could hardly be overlooked, the ancient names of these cities, not to speak of their history, were gone from ordinary memory. That knowledge lived on in the Jewish legends and amongst Greeks who were more learned than Xenophon. Maybe he did not ask carefully, for it is obvious that much later travellers were aware that these ruins were the remains of Nineveh.

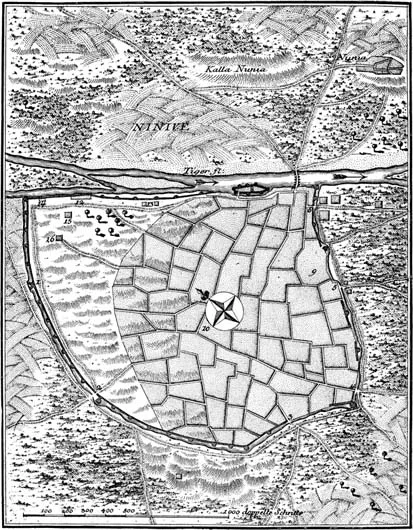

A visitor from Europe, the rabbi Benjamin of Tudela, passed by here as early as 1173 and saw Nineveh’s ruins – ‘now quite decrepit’ – and a few more had visited them after him (Pallis 1956). In March 1766, some seventy-five years before Botta and Layard met in Mosul, Carsten Niebuhr had spent a few days here on his way home from the disastrous Danish expedition to Arabia Felix (Hansen 1962; Rasmussen 1990; Niebuhr 1774–8). We know that Botta had read the great account of this journey published by Niebuhr, but it is unclear if Layard had heard of him. Niebuhr gives a map of Mosul (see Figure 1.2) which shows an area he calls Nineveh across the river; he has marked the two large mounds: the smallest to the south is shown as a modern village, which bears the name ‘Nuniya’, whereas the larger one to the north is called ‘Kalla Nuniya’, that is, ‘the Castle of Nineveh’. Niebuhr says that there was a village located also on this mound and it was called ‘Koindsjug’; this is obviously the same name which is now given to the mound as such, ‘Kuyunjik’, under which it appears in the archaeological literature.

The long lines of fortifications, the vast walls of ancient Nineveh, are not to be found on Niebuhr’s map; they run around the entire area and was the only feature noticed by Xenophon, but Niebuhr simply did not see them when he rode through the area on his way to Mosul. He presumably first took them for natural hills, and since he never had an opportunity to measure them carefully he naturally had to ignore them on his map. As a child of the Enlightenment he could not simply invent or guess and draw some lines where they might have been. He does give a special view of the village he calls Nuniya, which he says was built around a mosque that according to Jewish and Muslim tradition contained the grave of the prophet Jonah (Niebuhr 1774–8: II, 360, 392). This is another memory of ancient Nineveh of course, for Jonah – the prophet in the belly of the Whale – was sent by God to Nineveh to warn its inhabitants to abandon their sinful lives.

Figure 1.2 The map of Mosul and Nineveh made by Carsten Niebuhr in March 1766. The city had shrunk within its medieval walls, and across the river, linked with a fragile bridge of boats, is the area of ancient Nineveh with the two mounds. (From Rasmussen 1990: 284)

Niebuhr’s drawing and map, although not very correct or aesthetically pleasing, was a major advance, but the real study of the site began with Claudius Rich, who was the ‘Resident’ in Baghdad, where he represented the interests of the great East India Company in the early nineteenth century (Lloyd 1955). In 1820 he made careful measurements of the whole of Nineveh and produced a remarkably accurate map in the report which was published in 1836, after his death. Here we find both the major mounds and the fortifications, walls which surround an enormous area and which are easily traceable in the landscape. We find the two mounds now called Kuyunjik and Nebbi Yunus, that is, the Arabic name for the southern mound, which means ‘the Prophet Jonah’. Rich recounts that he was told that local people had, a few years earlier, found ‘an immense bas-relief, representing men and animals, covering a grey stone of the height of two men’. He also says that ‘all the town of Mosul went out to see it, and in a few days it was cut up or broken to pieces’. On Nebbi Yunus he saw large blocks of stone with inscriptions in some of the houses, some of them apparently still in their original place.

One of these, a piece of a slab of alabaster with cuneiform writing on it, was located in the kitchen of a miserable house, and it seemed to be part of the wall in a small passage ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of plates

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Part I: The First Explorers

- Part II: The Excavation of Sennacherib's Palace

- Part III: Victor Place and Hormuzd Rassam

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Conquest of Assyria by Mogens Trolle Larsen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Arqueología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.