![]()

1 Becoming a teacher through practical knowledge

Javier Calvo de Mora

The focus of this book is on providing resources and ideas to help university policy makers and school education stakeholders in developing appropriate forms of internship within programmes of teacher education, as well as a comprehensive dialogue on the fact that practical knowledge could be an important premise for educating teaching professionals.

From both sides of the Eurasian continent, transnational governments such as the European Commission (2010) and international organizations like Asia Society (2012) are standing for an innovative and creative teacher professional role, with autonomy to take decisions aimed to generate spaces and learning opportunities for all students. This suggestion implies a radical change in teacher education programmes around the world. In this context the intention of this book is to contribute to the debate about the new challenge of teacher education based on practical knowledge. Our contribution to this global discussion will be to provide an institutional narrative about partnership between universities and schools to sustain a process of action–reflection on the profile of the professional teacher, and to suggest new structures of participation and collaboration amongst schools, teachers, university providers, parents, policy makers and other stakeholders across education teacher programmes.

To carry this out institutional partnerships are needed to develop some strategies of research and reflection based on new competencies and skills proposed by international agencies, leadership in the classroom and in the school community, innovation in processes and strategies for assessing the work of their students and work on processes of continuity and cooperation between the social and cultural environment as well as the school environment. These objectives need to innovate a new institutional design in teacher training for the introduction to the teaching profession. It is here that this book is categorized: institutionalize collaboration between the Faculty of Teacher Education and infant, primary and secondary schools, in which knowledge institutionalization is identified as practical teacher training, i.e. the acquisition of skills and professional competencies through reflection and action taken in real-life school situations.

Teaching is a human activity and a social process intended to promote different types of learning. The actions of teaching and learning involve mental requirements: social/emotional relations, cultural understanding, and an institutional framework to give continuity, compliance and legitimacy to influence and ensure acceptance of both aspects involved in the process based on mutual and reciprocal trust in those who teach and those who learn.

Our first experience of the relationship between teaching and learning occurs in the first days after birth. It continues throughout our lives across different spaces and times. A significant part of this experience occurs in the school, created in different countries, decided upon by elite governments in relation to what to transmit and how to influence the hegemonic culture and more. It is orientated towards the creation of societal norms, knowledge, technologies, beliefs and behaviors accepted and recognizable by those who planned them.

Becoming a teacher has a double contradictory dimension: to learn what mainstream teachers do at schools and to learn how potential teachers could access knowledge of the reality of schooling. And in relation to these two aspects, the teaching profession is exposed to strong influences from the context in which teaching and learning takes place.

What do teachers do at schools?

This book is about the institutionalization of learning in schools. In this school space teachers play a role in how best to present selected content, implement pedagogical strategies, understand how students learn, and certificate the success of learning to society as well as the social, cultural and political elite who determine the demands to be placed on teachers.

Nowadays, this process of acceptance and trust in educational institutions is breaking down because of global access to information and global freedom to create networks of learning. And the traditional teaching profession has to accept new challenges, social structures, new goals, new stakeholders and participant members as well as new technologies for learning and teaching. In this regard there are many proposals around the world for the restoration of the institution of the school by including new learning content, student activity and new teaching processes to create a framework of trust influenced by a global education system, not merely a state or national system such as it appeared to be in the 20th century (Calvo de Mora 2000).

The target in this global scenario of teaching and learning is to create institutions in which a new sense of belonging should be the main challenge to take into account, for all people without distinction from birth to, at least the secondary period of schooling under acceptable conditions of equity. In other words, around the world, teachers who are committed to the profession of teaching are needed, and open access schools are needed in which students can be educated over long periods from early childhood to secondary level with the objective of creating a sense of the ‘growth mindset’ (Dweck 2012) in the student body with a look of complicity between human and institutional learning.

Another global consensus is that student teachers demand to be trained and educated through practical knowledge of teaching and learning in a diverse array of ways and strategies which might be conceptualized in terms of internships and practicum periods. This professional education is supported not only by the passive reception of educational content, but as a reflection of the realities of teaching and learning encountered everyday in different contexts of education in schools, non-formal educational organizations and informally in the community as sites of knowledge.

The teaching profession has always been a creative, cultural job (Freire 1998). In this conceptual framework, this book localizes practical knowledge on teacher education. Practical knowledge of the teaching profession means learning how to become a creative professional in a global context. Every teacher has a teaching method, their own routines, strategies for decision making, appropriate ways to control spaces and times throughout each academic year, knowledge of how to manage the classroom as well as how to balance merit and worth in the student assessment process. These professional actions contribute to the creation of their theory of expertise about how to implement the teaching tasks through a natural, local and subjective learning process based on reflection on everyday experiences. A side effect of this learning process is teachers deciding to abandon the profession because of its system pressure, and problems with the continuity of a ‘normal’ job, with students, and schools where pressure, misconceptions, low salary, weak societal appreciation of the teachers’ role and scarcity of teaching resources impede the implementation of personal ideas about teaching and learning. In other words, the teaching profession has always been a complex one, sometimes overshadowed by pastoral care and guidance which nowadays is difficult to sustain due to the impact of mass media on social and emotional experiences.

Nowadays, unfortunately, teachers are educated in guidance and learning control to transmit information and care in relation to the behavioral discipline of their students. The paradox is that these students are refusing this care and guidance and the effect of this is that teachers want to abandon the profession.

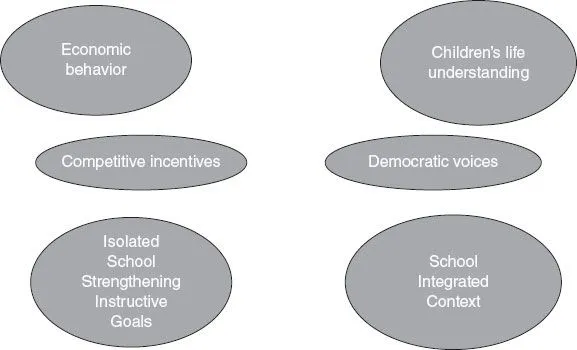

The dualism between the continuation and abandonment of the teaching profession could be interpreted as a dilemma between two contradictory focuses on the meaning of practical knowledge: an economic culture approach versus a social culture approach to the teacher’s role. An economic approach to culture promotes design and facilitates teacher job traits embedded in the performance of standards of knowledge production. In contrast, teachers who follow a social interpretation of culture conceptualize and give meaning to learning both inside and outside school settings, which proposes a subjective approach as well as a qualitative dimension of the teacher role. Figure 1.1 represents two contradictory approaches to practical knowledge earlier mentioned: Economic Behavior, and human learning based on the evolution of neuro-education in innovation, creativity, questioning and other active ways of learning – Children’s Life – visualized in interests, citizens and freedom voices. Economic behavior is understood as looking for success awarded by incentives given to students across an ordinal table of results of efficacy; in this sense schools are ‘neutral’ and isolated institutions identified by rational procedural standards which assure the correct way to reach appropriate goals of success. Across this ideal model, students of education must manage indicators of teaching through different subjects and assess how to assure the quality of accomplishment of the standards of learning. Opposite this narrative, some cultural and social readings of schools are considering a global vision of students’ learning to become citizens for democratic societies, in which knowledge is appreciated not only as a tool of success but of personal and collective empowerment. And according this ideal type, schools are community spaces in which the socialization function goes beyond the curriculum content domain until reaching social and cultural ethic behaviors.

Figure 1.1 Dilemmas of teachers’ decisions

On the other hand, narratives of economic behavior are represented by educational global organizations (OECD 2013) whose performance rating shows the way in which young people are trained for today’s economy behavior trends, by the quality of learning outcomes, constant effort, incentive of productivity and obedience to external regulations. They are supposedly aided throughout a change of education policy based on a high-performance system, as well as the practice of teachers, who are collaboratively leading a belief that all children are capable of success, achieving world-class standards at each school. This framework of good practices considers schools as self-sufficient entities that can promote what good performance is into a professional form of work in learning organizations related to the innovation of efficient pedagogical practices for which competitive incentives are behaviors given as added values rewarded at schools and are using them as indicators to provide rating scales of society, parental choice of school and governmental deliveries.

Teachers around the world are facing this dilemma: teaching according to some standards of good student behavior as well as successfully reaching comparable learning results across league tables, or teaching taking into account student identities by proposing goals adjusted to a singular population of the student body. In terms of practical knowledge, teachers must do these apparently contradictory jobs: generate trust on the economic systems and create spaces of sense of belonging on the part of their groups of students.

Today, global school policy endorses an instrumental pragmatic view considering each school approach to change as an isomorphs entity in a business organization, where citizen workers are trained to adapt knowledge of economy demands (Lelliot, Pendlebury and Enslin 2001) by implementing a hierarchy of positions and roles on basic cognitive and behavioral competencies such as Mathematics, Science, English and TICs (Anyon 1997: 135–39) forming a closed circle of acceptance of ‘true knowledge’ – as well as rejecting and excluding non-formal knowledge that is not as accountable as merit – in which a narrative of excellence, good practice, price, incentives, and so on is built. The main objectives are one array of standardized learning outcomes expected for students (Sachs 2005; Darling-Hammond and Lieberman 2012, p. 54), and being teachers considered as civil servants since they are accountable in respect to government education law.

Inconsistencies in this hegemonic economic behavior, from my point of view, are that schools are created by experts and policy makers who want to establish a global school institution. This concept means searching for homogenization of schooling, mentioned elsewhere as isomorphism using the ‘Starbucks’ and ‘McDonald’s’ strategy (Calvo de Mora 2012: 55–9), throughout a learning process of the individual performance canons (Brown and Tannock 2009; Ball 1998, 1999; Porfilio and Carr 2011) supported by the utopian Bloom’s 2 sigma problem of the correct educative social relations (Bloom 1984). In other words, schools focus on isolated individuals who need to become high achievers in institutional goals, and ‘strive for accuracy’, both inside and outside of schools, in duties and responsibilities regarding the learning standards chosen by each institution.

But, millions of children are left behind and are motivated by extra tutoring help at home (Bray 2010) and by informal organizations, whose effects are really known as ‘parallel school system’ (Ball and Youdell 2007; Ball 2009) for privatizing in such way as complementary student learning opportunities through academic services by improvement of academic skills needed for standard success: engaging students with appropriate types of exams scored at schools, effective feedback focus on items of information needs to pass external exams, and so forth.

Teachers are also bound by an ethic of social responsibility (Ball and Youdell 2007). Because of discrimination and poor consideration towards teachers’ action in their classrooms, they protest – at least in the Spanish context – of internal selection of students at schools (Calvo de Mora 2011) where teachers’ role is as a technician or middle management position at classrooms; on the contrary a professional profile requires teaching to be carried out with competencies to understand students’ motives to learn, their expectations and strength of character, and other inner inclinations enclosed in the culture that students are living (Smith 2013). And to gain knowledge about children it is better to access the social and emotional context of their peers, families, leisure, technologies they use, fashion, music and games, that is to say, diving into the life world of children (Habermas 1987).

Teachers should appreciate as well as recognize knowledge created and decisions taken from open and democratic social relations created by the large diverse population involved in the socio-cultural reality of each school, action, reflection and communication unde...