![]()

Memory and Democratic Pluralism in the Baltic States — Rethinking the Relationship

Eva-Clarita Pettai

Memory and how it interacts with democratic politics remains a thriving theme within both academic and public debate.1 In the Baltic states, memory has resonated in both domestic and international politics, as in 1990, when the three countries defined themselves as formally occupied, and finally restored their independence and democracy. The subsequent public and academic controversies that erupted around this representation of the past both on the domestic and international stage testify to the continuous presence of the past in this region (cf. Lehti & Hackmann 2008; Berg & Ehin 2009; Wezel 2008; Onken 2003; Snyder 2002; Budryté 2005). These 'memory wars,' as they have been termed (Brüggemann & Kasekamp 2008), as well as recurrent uses of the past for political claims among policy-makers, can be seen as inevitable in a process by which the young nation-states seek to establish 'historical truth' after fifty years of totalitarian memory manipulation and historical falsification. Past myths and propaganda, for example, the Soviet stereotype of the 'Baltic fascists' or the Nazi propaganda of the 'Jewish-communist guilt," can still be found in populist campaigns or internet blogs, forums or letters to the editor. Indeed, the fact that these stereotypes still appeal to many shows that a lot of groundwork in terms of historical clarification and historiographical rectification remains to be done (Weiss-Wendt 2008; Nollendorfs & Oberländer 2005). However, overcoming stereotypes and deconstructing myths is only one part of the process. The more radicalized outbreaks of recent public violence surrounding days or symbols of collective remembering2 indicate that parts of society experience the establishment of 'historical truth" as a state-sponsored policy of exclusion. From their perspective the independent Baltic states are forcefully establishing and institutionalizing a particular narrative of the state and nation that ignores many personal experiences and memories. As we will show in this collection of case studies, the mechanisms of in- and exclusion do not run exclusively along lines of ethno-cultural (Russian vs. Baltic) belonging. Rather, many different groups and individuals in society continue to struggle for recognition, representation and participation in the construction of collective memories and political identities in a pluralist democracy. The means to achieve this vary and large public controversies or demonstrations are perhaps only the more visible signs of the struggle. As long as they remain non-violent, they can be seen as a healthy byproduct of a democratization process that goes far beyond institutional and legal settings.3

The contributions to this volume examine the divergent social memories that exist in Baltic societies today. Coming from various disciplines and methodological backgrounds, the five empirical cases encompass an exploration of nostalgic memories of the Soviet period carried by rural and urban residents of Lithuania (Neringa Klumbyté); a critical analysis of a recent survey among teachers and students in majority and minority schools in both Latvia and Estonia with a focus on the teaching and reception of the countries' history (Maria Golubeva); a study of memory and political empowerment among Lithuanian female politicians who have experienced deportation (Dovilé Budryté); a discussion of professional self-perceptions and political attitudes among Estonian historians of different generations (Pertti Grönholm and Meike Wulf); and finally, an exploration of public debates among intellectuals and politicians in Latvia over lustration policies (leva Zake). In a concluding theoretical and philosophical article Siobhan Kattago reflects on possible ways of reconciling the multiple, at times contrasting, memories and actors that exist in the Baltic societies today with the ideas of democratic pluralism.

In the first part of this introduction, I will outline a general conceptual framework for a more nuanced study of collective memory in its relationship to democratic politics. The aim is to show how aggregated individual and social memory empowers different types of societal actors to seek influence in or interact on a variety of levels with the political world. In turn, different prevailing top-down-imposed memories can prompt different types and degrees of societal, bottom-up reaction. I will outline a detailed model that identifies various types of actors and modes of interaction. Part two will briefly discuss the current state of studies on 'the politics of memory' in the Baltics in order to then present the case studies in this volume as they contribute to the outlined model. By disaggregating and illustrating the different bottom-up instances, we intend not only to improve Baltic research in the field of memory politics. Moreover, our aim is also to further research in the field, as this more precise operationalization of how to study bottom-up processes of memory contestation should be widely applicable elsewhere.

‘Collective memory’ — from above and below

Research on collective memory has long sought to sharpen the original application of the term that goes back to Maurice Halbwachs' studies of the social frameworks of individual memory (Halbwach 1992 [1925]; cf. Misztal 2003). As Jeffrey Olick and others have pointed out, Halbwachs' theories on collective memory suffer from a fundamental tension between two different phenomena: that of collective memory as an aggregate form of individual memories, and of collective memory as 'commemorative representations and mnemonic traces' (Olick 1999, pp. 335-36). The former understanding maintains that only individual human beings are able to remember through highly selective and scattered neuronal processes. However, much of our individual remembering only takes place because we actually attach our memory to the memories of others. 'When people come together to remember, they enter a domain beyond that of individual memory' (Winter & Sivan 1999, p. 6). In fact, as psychologists point out, individual memory remains fragmentary and episodic unless it is embedded in communicative frameworks based on language, rituals and modes of behavior as much as on external media such as books, films, etc. Individuals, consciously or unconsciously, construct, redirect and adjust their personal memories within this framework to create meaning for themselves. This can lead to a situation in which 'our autobiographical memories, i.e. that which we think to be the core elements of our life-story, [are] not necessarily root[ed] in actual own experiences' ( Welzer 2002, p. 12).

Individual memory can thus be denned as a 'dynamic medium of subjective processing of experiences (Erfahrungsverarbeitung)' developed within a 'milieu of spatial closeness, frequent interaction, common ways of life and shared experiences' (A. Assmann 2006, p. 25). The dividing line between individual and social memory is most difficult to detect. As Jan Assmann (1995) has pointed out, 'individuals remember in order to belong' and their 'memory' can go far beyond their own life span. Thus, the communicative process through which individuals associate and identify themselves within larger social entities stretches much further than only to the immediate family and community and encompasses whole generations. The immediate interpersonal contact and 'spatial closeness' that has characterized individual memory and 'small face-to-face societies' is lost at this level of social memory. In order to generate shared values, beliefs and attitudes among larger entities, individual memory is attached to symbolic media in a broader public-communicative space and they are 'conveyed and sustained by (more or less ritual) performances' (Connerton 1989, p. 4). In this way individuals can share historical perceptions with people they have never met either because they were born into a specific religious culture, or because they belong to the same age cohort within a similar social, political and cultural context (A. Assmann 2004, p. 23). Gender can equally determine historical experiences and the way they are processed and communicated over time and in larger social contexts. In this publication, Budryté aptly notes, 'As a mode of discourse, a "backbone" of social relations, gender becomes a crucial variable in the construction of collective memory.'

It is on this level of societal interaction and construction that social theorists suggest to talk about a collective form of memory, about memory as a 'publicly available social fact' (Olick 1999, p. 336; cf. Bell 2008; Misztal 2005). Such collective, social memory relies on symbols and on commemorative rituals and practices that make it a fundamentally 'mediated memory.' At the same time, it still shares a common feature with more narrow formations of memory such as family and 'interactive group memory' in that it is fundamentally 'grounded in lived experiences' and human interaction, therefore unstable and temporally limited (A. Assmann 2008, p. 55). Moreover, many social theorists have suggested to limit the use of the term 'collective memory,' if used at all, to this form of 'embodied and intergenerational,' dynamic and ephemeral social memory (Gedi & Elam 1996; Winter & Sivan 1999; Bell 2008). They are most wary of the existence of a 'memory' beyond human, communicative interactions, ultimately grounded on individual, neuronal processes of remembering. Instead, they suggest to adhere to more conventional terms such as 'myth,' 'ideology' or 'tradition' in order to describe historically informed public-political representations of the past and collective identity constructions.

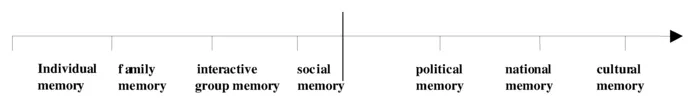

This is not the place to delve any deeper into these theoretical debates. There is certainly a danger of overstretching the concept of collective memory and thereby confusing analytically distinct phenomena. In order to develop the conceptual foundation for the case studies presented here, however, it nevertheless seems worthwhile to stick for a while longer to the term 'collective memory.' We therefore follow Aleida Assmann's suggestion to take it as an 'umbrella term for different formats of memory that need to be further distinguished' (2008, p. 55). Among them, she finds, are also levels of historical consciousness no longer attached to individuals' primary experiences and social, 'embodied' interaction. In order to understand the multiple ways and means by which individuals organize their memories and construct their identities, she argues, we need to move further 'in space, time and complexity' and look at what she identifies as the political, national and cultural formats of memory. Drawing on several of Assmann's most recent works (2004, 2006 and 2008), we can visualize these types or formats of memory on a horizontal scale stretching from the 'individual' all the way to the 'cultural,' thereby increasing the spatial and temporal scope of memory.

Graph 1: 'Formats of memory' according to Aleida Assmann (2004 and 2008)

In order to generate historical awareness and a sense of shared beliefs and values among large groups, such as whole nations, historical meaning needs to be attached to more stable and 'durable carriers of external symbols and material representations' like monuments, texts, symbols, and images. Thus, a fundamental shift (symbolized by the vertical line in Figure 1) takes place from a short-term, 'implicit and embodied' social to an institutionalized and transgenerational form of memory (A. Assmann 2004, p. 25).

Our interest here lies on the political (and national) dimension of memory as a form of structural power that works through radical selection and simplification, high symbolic intensity and emotional appeal. As such, it engenders identification and works as a kind of 'matrix of meaning' for nationally conscious individuals (Müller 2002, p. 21). Indeed, as A. Assmann (2004, p. 36) points out, it is the political memory that is truly 'collective' in that it 'generates together with a strong sense of loyalty also a strongly unifying we-identity.' For this collective (national) identity to thrive, the actual historical circumstances surrounding experiences no longer matter. Rather, these experiences are transformed into highly simplified narratives and myths of the political community that transcend the lifetime of individuals and even generations. Thus, the formation of ideologies and collective identities come into focus when we study the top-down institutionalization of memory in society. This can be studied in the framework of nation-building and nationalism (Hobsbawm & Ranger 1992). It can be equally well highlighted in contexts of regime transition when issues of retroactive justice may or may not define political institutionalization, public perceptions and political identities in the new state (Barahona de Brito el al. 2001; Elster 1997; Teitel 2005). However, once democratic institutions are consolidated and dominant narratives of the past established, the delicate interaction between memory and liberal democratic politics still remains. Political scientists and social theorists have, therefore, tried further to conceptualize the link between memory in its collective forms and everyday politics. They discuss how memory translates into power through legitimacy and interest (Müller 2002); how it impacts on political culture by working as positive and negative cultural constraints (Olick & Levy 1997); and how debating memory and the past can contribute to the 'deepening' of democracy (Misztal 2005).

Democratic polities have many options of how to deal with the plurality of social memories that are continuously generated and appropriated in changing political and socio-economic contexts. Through legal provisions, political regulations, material representations and symbolic acts, certain social memories can be acknowledged and even propelled center-stage. They can also be ignored, depending on whether they are conducive or obstructive to the discourses of political (national) legitimacy and/or the pursuit of particular short-term interests. As Klumbyté observes, 'paradoxically (...), laws and other initiatives, although aimed at homogenizing memory and identity, reproduce the difference between memory communities.'

Outlining a model for analyzing societal-political interaction over memory

The bottom line of many studies on the politics of memory is that the mechanisms for molding public memory to support a particular political direction take place also in open and democratic societies. Not least through history education in public schools, public commemoration, political speeches, monuments and museums, a collective (political) memory is forged that creates a sense of loyalty among the majority of citizens of a state (McNeill 1989; Wolfrum 1999). Memory-politics relations are thereby analyzed predominantly as a top-down process by which a political and intellectual elite determines what is remembered and what is forgotten in society. 'For it is surely the case that control of a society's memory largely conditions the hierarchy of power,' as Paul Connerton (1989, p. 1) has pointed out.

Another way of approaching the question of how exactly memory relates to politics in pluralist democracies, however, is to focus on the opposite process, that is, the ways in which societal actors with certain socially generated memories seek political capital or gam political power in order to change dominant narratives. The most obvious examples of such bottom-up memory contestations are cases in which groups of former victims of injustice fight not just for political rights or legal status, but also for official apologies and reparations. By doing so they claim membership in the wider community of citizens by having their memories included in the official narrative of the state and nation (Barkan 2000; Torpey 2003; Wulf 2007). Yet, not all individuals or groups whose primary experiences and memories are absent from dominant discourses translate this mismatch directly into political action. Instead, they may interact in other ways, some of which will be profiled in the cases studies to follow.

To fully understand the role memory plays within democratic power relations and pluralist societies we need to understand the plurality of 'memory actors,' that is, individual societal actors who are part of and, in some cases, active agents of a particular social memory. At the same time, the organizational levels on which these social memories are generated need to be identified as well. Each of the memory ...