![]()

Contrasting Responses to the International Economic Crisis of 2008–10 in the 11 CIS Countries and in the 10 Post-Communist EU Member Countries

ROBERT BIDELEUX

Robert Bideleux is Reader in Political and Cultural Studies at Swansea University. He is currently writing books on genocide, Orientalism and global political economy. His History of Eastern Europe (2nd edition, 2007, with Ian Jeffries) has recently been published in Chinese translation in Shanghai.

Far from being uniform and amenable to broad generalizations, the consequences of the international economic crisis of 2008–10 for the post-communist states have been strikingly diverse, and the policy responses of these countries to those crises have been correspondingly varied. The 11 Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) countries, and the 10 post-communist states admitted into the EU in 2004 or 2007, were affected in different ways by the economic crisis and offered different responses to it. These widely differing impacts and responses can be satisfactorily explained and conceptualized in terms of relatively concrete and tangible differences in the structures of power, resources, opportunities, incentives and constraints that have emerged in these two broad groupings of countries. The economic systems that have emerged in most of the CIS countries have diverged substantially from those of the post-communist states that joined the EU, with significant cautionary implications for future attempts to integrate or associate CIS countries with the EU.

This contribution began life as a paper written in response to an invitation to speak at the US Department of State in Washington, DC, in June 2009 about the likely responses of Eastern and Central European and Balkan post-communist states to the international economic crisis that had escalated rapidly between September 2008 and April 2009. The State Department and the new Obama Administration were concerned that these crises could precipitate major social and political unrest and destabilize these still relatively new and fragile democracies and market economies.

Without wishing to detract in any way from the mostly remarkable and impressive successes of democratization and marketization in the post-communist Balkans and Eastern and Central Europe, I emphasized that the colossal setbacks suffered by European democratization and international trade and investment during the 1930s and 1940s had demonstrated the inherent fragility of such processes, and that this in turn highlighted the vital importance of the European Union (EU) as a supportive framework for political and economic liberalism and the rule of law. During the economic crisis of 2008–9, the existence of the EU (in particular its legal, institutional and policy frameworks) played crucial roles in containing or pre-empting potential surges of support for the kinds of beggar-my-neighbour protectionism, economic nationalism and virulent ultranationalist xenophobia which together had transformed the European economic, social and political crises of 1929–31 into the 1930s Depression, the spread of fascist or authoritarian ultranationalist rule to nearly two-thirds of Europe’s states by 1937 (even before the start of major military occupations), and strong growth of mostly Stalinist communist parties, culminating in the outbreak of total war. I also stressed that the present-day adult populations of Europe’s post-communist states were for the most part poor, disillusioned, demoralized, atomized, weakly unionized, worn down by ‘transition fatigue’, somewhat inured to seemingly endless hardship and upheaval and disinclined to join political parties, social movements and public protests. Consequently, the predominant response of these populations to the economic crisis of 2008–9 (as it then was) would not be to engage in protests and unrest leading to destabilization, but, on the contrary, to grit their teeth, keep their heads down and work even harder than before, in the hope or expectation that this crisis would (like previous ones) eventually blow itself out and allow people to get on with their lives. (This prognosis has been reasonably accurate, other than in Kyrgyzstan and potentially Tajikistan, but they are exceptions for reasons that are only partly related to the impact of the international economic crisis.)

The CIS countries were included in the long paper that I presented to the State Department in June 2009 mainly because there were already illuminating contrasts to be drawn between the CIS responses to the economic crisis of 2008–9 and those of the post-communist states that had joined the EU. These themes are central to the discussion that follows, which argues that these divergences can be satisfactorily explained and conceptualized without recourse to cultural stereotyping and ethnocentric caricatures. The main emphasis here is on the centrality of the structures of power, resources, opportunity, incentives and constraints within which both rulers and ruled have had to operate, in explaining and conceptualizing impacts and responses. Length constraints have made it necessary to refrain from drawing comparisons with the impacts and responses in the Western Balkan countries, to curtail commentary on individual countries and to concentrate on the economic dimensions.

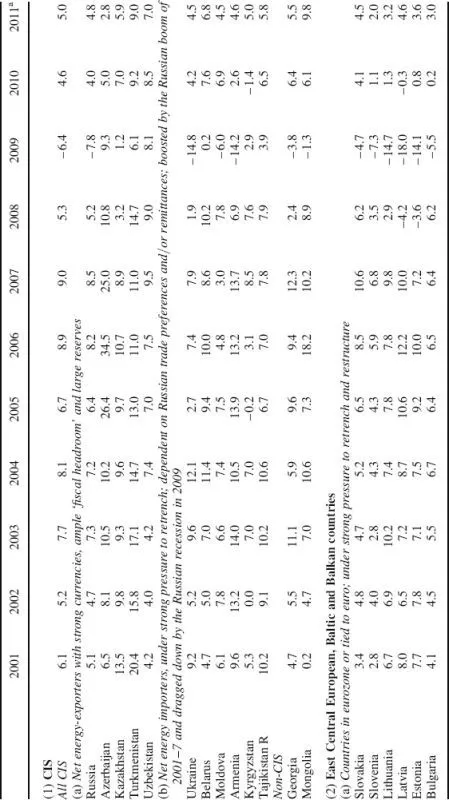

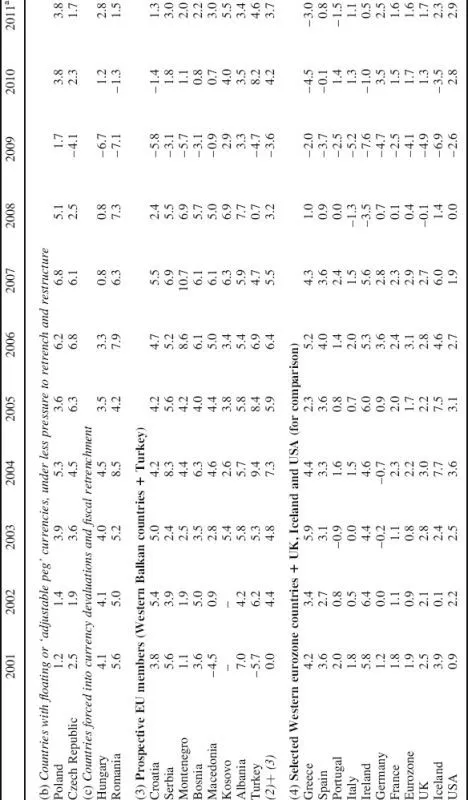

The Booms in Europe’s Post-Communist ‘Emerging Economies’, 2001–7

As in much of the rest of the world, the economic crisis that convulsed the post-communist states in 2008–10 was preceded by spectacular economic booms (Table 1). Europe’s ‘emerging economies’ (the post-communist states plus Turkey, in IMF parlance) grew at an average rate of 5.9 per cent per annum from 2001 to 2007, surpassed only by Asia’s ‘emerging economies’.1 Indeed, the Eastern and Central European economies were then growing fast enough to catch up with Western Europe within 20 years, in per capita gross domestic product (GDP).2

Following painful economic ‘liberalization’ and structural reforms in the early to mid-1990s, these booms consummated the economic recoveries that began in the mid-1990s in Eastern and Central Europe, the Baltic states and some Balkan states; after the 1999 Kosovo conflict in other Balkan states; after the economic crisis of 1998–99 in the CIS and after the economic crisis of 2000–1 in Turkey.3 The booms were driven partly by rapid growth of consumption and of service activities and partly by high levels of investment, including foreign direct investment (FDI); and they more than reversed the 5 per cent per annum contractions in GDP that had taken place in these regions between 1990 and 1995.4 They were mostly accompanied by transformations of economic structures, including substantial upgrading of the composition, quality and technological sophistication of manufactured exports, at least until 2004, allowing these economies to maintain export-led growth even after exchange rates and personal incomes began to rise significantly in real terms.5

During the 2001–7 booms, however, most of Europe’s post-communist states ran current account deficits which by 2008 averaged some 11.5 per cent of GDP, financed partly by major inflows of FDI from Western Europe, but

largely by the borrowing of subsidiaries of foreign banks from their [mostly Western] parents. The banks used this relatively cheap foreign funding to extend credit to households and nonfinancial firms. This resulted in rapid growth of domestic credit, denominated mostly in foreign currency in almost all the countries. Credit went largely into financing nontradables [especially real estate] and imports of consumer durables.6

Many of these countries thus became over-dependent on external funding. Cross-border banking flows reached 13 per cent of GDP in some cases, and by 2008 ‘emerging Europe’s stock of bank liabilities to advanced countries exceeded 50 per of its GDP, about three times the ratio for other emerging markets’.7 Reliance on foreign banks and their loans (mainly denominated in foreign currencies) generated large debt rollover requirements in the private sector, excessive growth of demand for non-tradables, economic overheating, inflationary pressures and large current account deficits, rendering them increasingly vulnerable to changes in external conditions. ‘Many banks in emerging Europe, although still appearing to be well capitalized and profitable, did not build sufficient reserves for future loan losses’.8 Thus, any hiatus in new loans from Western parent banks to their subsidiaries in these countries was likely to precipitate major economic contractions.9

TABLE 1

ANNUAL RATES OF GDP CHANGE IN THE POST-COMMUNIST STATES, 2001–2011 (PERCENTAGE CHANGES IN REAL TERMS; IMF ESTIMATES AND PROJECTIONS)

Sources: IMF, World Economic Outlook, April 2009 (Washington, DC: IMF, 2009), pp. 190, 194; and World Economic Outlook, April 2011 (Washington, DC: IMF, 2011), pp. 182, 185.

Most of these countries, especially those with balanced or almost balanced budgets and low or manageable public and private debt, were relatively unaffected by the initial stages of the Western financial crisis in summer and autumn 2008. They still managed to grow in 2008, albeit more slowly than in 2001–7 (Table 1). As late as October 2008, by which time major Western ‘advanced capitalist economies’ were seriously contracting, the IMF still expected the CIS economies to grow by 5–6 per cent, and the new EU members to grow by 3.5 per cent, during 2009.10 This rendered most post-communist states all the more unprepared for the economic tsunami that hit them in late 2008 and early 2009. Almost overnight, most of Europe’s ‘emerging economies’ became ‘submerging economies’.

CIS Responses to the International Economic Crisis of 2008–10

Andrei Shleifer and Daniel Treisman have famously claimed that by 2000 Russia had become ‘a normal, middle-income capitalist economy’, indeed ‘a typical middle-income capitalist democracy’; and, while ‘Russia’s big business is certainly dominated by a few tycoons … in this respect, Russia is typical of almost all developing capitalist economies … Oligarch-controlled companies have, in fact, performed extremely well – better than many comparable companies that remained under the control of the state or Soviet-era managers’.11

If this had been a sound assessment, such a ‘normal middle-income capitalist democracy’ (contributing approximately 71 per cent of the CIS countries’ aggregate GDP) would surely have tried to lead, shepherd and cajole other CIS countries towards similarly ‘normal’ economies and polities, so that they could all live happily together as ‘normal democratic capitalist states’. Instead, the Putin regime contributed to the containment or reversal of the ‘coloured revolutions’ of 2003 (Georgia), 2004 (Ukraine) and 2005 (Kyrgyzstan), which had initially aroused great hopes that democracy’s hour had finally struck within the CIS. In 1998 Grigory Yavlinsky offered a more convincing characterization of Russia’s economy and polity:

Far from creating an open market, Russia has consolidated a semicriminal oligarchy that was already largely in place under the old Soviet system. After communism’s collapse, it merely changed its appearance, just as a snake sheds its skin. The new ruling elite is neither democratic nor communist, neither conservative nor liberal – merely rapaciously greedy.12

Sadly, most CIS countries have remained deeply ensnared in relatively harsh and hierarchical ‘Hobbesian’ environments characterized by (i) strong ‘verticality’ of power structures, perpetuating very autocratic, hierarchical, top-down power relations; (ii) relative weakness of more ‘horizontal’ networks and relations (the rule of law, ‘level playing fields’, horizontal accountability and civil society associations) and (iii) relatively weak integration into big, open and more pluralistic and fiercely competitive external markets. These factors both reinforce and are reinforced by in-built structural biases towards ‘dealing’ and ‘rent-seeking’ (rather than more productive activities). These biases are most strongly embedded in, and maintained by, the ‘rentier state’ structures and characteristics of the region’s major energy-exporting countries (Russia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan), and also, to lesser degrees, in those states that receive smaller but none the less substantial indirect ‘rents’ (transit fees) from oil and gas pipelines traversing their territories (Belarus, Ukraine and Georgia) and from the re-export of petroleum and gas products produced from oil and gas imported from Russia (in the cases of Belarus and Ukraine).13 Indeed, Ukraine has in recent years received between $2bn and $3bn per annum in oil and gas ‘pipeline rents’ (transit fees), besides more covert indirect ‘rents’ from (re-)exports of Russian and Central Asian oil and gas to EU countries.14 Energy re-exports made up an astonishing 22 per cent of Belarus’s GDP in 2008.15

These features have perpetuated (i) highly clientelistic, sometimes criminal or semi-criminalized, relatively closed, and very incompletely marketized economic relationships and networks;16 (ii) the so-called ‘soft budget constraints’ and the hidden subsidization of economic inefficiency which bedevilled the former ‘command economies’, that is, the near-absence of the constant, effective and all-pervasive financial–budgetary and commercial–competitive pressures to cut costs and increase efficiency (factor productivity) which characterize more open and more fully marketized economies, including those that joined the EU in 2004 and 2007.17 These deeply entrenched structural features generate and sustain powerful vested interests that engage in extensive ‘state-capture’ and market-sharing collusion and are experts at resisting or emasculating endeavours to restructure and reform these systems.

The energy sector (electricity, as well as oil and gas) plays crucial but largely hidden or non-transparent roles in perpetuating these networks, power relations and distortions, far exceeding the roles suggested by the offic...