![]()

Chapter 1

Fantasies of the cut

We must see right away how crude it is to accept the idea that, in the ethical order itself, everything can be reduced to social constraint… as if the fashion in which that constraint develops doesn't in itself raise a question…1

Scenes of torture and of female genital mutilation2 are imagined as scenes of pain and of incisions into the flesh. Both are scenes where someone is described as being held down. Both are scenes where flesh is manipulated, stressed or cut and both are scenes that have attracted the specific attention of human rights advocates, of domestic laws and of human rights doctrine. The flesh of the so-called ‘mutilated woman’3 is imagined to require protection from the cut. And the flesh of the tortured is often sacrificed to the flesh of democratic polis: The People. The value of the flesh — how much can be cut and what remains — is a measurement which employs doctrines of biomedicine, law, human rights and political theology. Flesh is worth something in the domestic and universal polis, but not all flesh is equivalent, not all bodies are uncut, not all humans are sacred.

The imaginations of female genital mutilation and of torture offer a way of trying to understand the disparities in law's attention and the modes through which law regulates life. The scenes are not the same — although female genital mutilation is often described as ‘torture’ — and they attract very different investments. Both practices evoke comment, but the violent outrage against female genital mutilation is certainly disproportionate to the quiet, and usually scholarly, objections to torture. About torture, the western subject is arguably ambivalent; about female genital mutilation… we are (almost) passionately united in a fight for the good, a fight, as Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has described, to ‘save brown women from brown men’.4 Subjects of western democracy, who identify with the values of liberal law, are rarely ambivalent about little (Muslim) girls being held down, while about the holding down of brown (Muslim) men… we're not so sure.

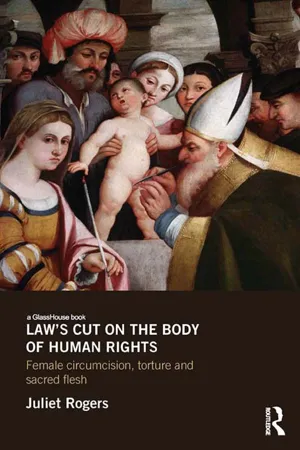

This book is a meditation on the scenes that have come to inspire law on the practices imagined to be female genital mutilation, and on torture, imagined to be interrogation. It is an examination of the fantasies that underpin these scenes as the political, legal and popular commentary on the practices and their products. In this book I contest that every law comes with an image. How else would we know what to constrain? Or why it need be constrained? But these images are not self-evident representations of cultural or legal practices: they are scenes which provoke rage, pain and excitement, and they are scenes which demand intervention, as the cut of law and the care of human rights. These scenes are particular, invested and haunted by the ordinary anxieties of subjects before law; anxieties that I will discuss as political and psychological. These anxieties can be understood, in a psychoanalytic idiom, as anxieties about castration, which are then heightened by the cuts of law: the cutting off of the king's head, the increased aggressions in democratic sovereigns (since 9/11), and even by the assertion of a universalism of human rights. The particular representations of scenes of female genital mutilation and torture alleviate some of these anxieties by turning the cuts toward another, but these scenes also announce the possibility of the cut arriving on the subject of liberal law. The scenes thus serve, like all scenes in a psychoanalytic idiom, to thwart castration, but these scenes are also legal scenes that announce the cut as prohibitions and, sometimes, arbitrary incursions of law. They are scenes which promote a demand for sovereign attention — as the attention of liberal law — and they are scenes which serve to thwart and announce law's cut: announcing a very violent cut, indeed.

There is a familiar scene of what is termed female genital mutilation. It is of a child held down, her legs parted, she is screaming while she is being cut with an unidentifiable piece of metal. This image is familiar because it is repeated. It is not easily forgotten for this repetition and for its disturbing motifs: the pain of a child, the loss of innocence and the loss of desire. It is the image presented as the justification and imperative for action on female genital mutilation and, like most images presented as violence, it is effective. More than that, it is seductive. It seduces us into believing the constraint is required, the prohibition is necessary. Something is being done, someone must be stopped — a child is being mutilated.

The call of mutilation is the call to law. The call to apply the law is not all that it seems, however. This is not simply a statement about the political investments and excitements that infiltrate and inform the processes of law's production. These exist, and they influence process and product, often in equal measure. The constraint of law, when accompanied by the images of violence, such as those that accompany initiatives to legislate against female genital mutilation, betray investments in the violence itself, or more precisely, in the scene of violence: the scene of the little girl being held down. This scene, I suggest in this book, is only part of the story. Just as the military and legal rationales for contemporary scenes of torture — in Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo Bay, and in black sites we can only imagine — are only parts of the story of why torture is accepted in liberal societies.

The stories of legitimation that surround the prohibition of female genital mutilation and the lack of objection to contemporary practices of torture offer insight into the ambivalences of a legal subject before liberal law. These are ambivalences about where and when the cut can and will arrive, about who deserves the cut and about what will protect the subject from the sovereign's displeasure. The stories of torture and female circumcision embody these ambivalences and are therefore not as simple as the books on airport shelves,5 as the legal and political rhetoric would suggest. These are stories of confusion and doubt about, what I discuss in this book as, the freedom from the cut, as a freedom from the mutilations and prohibitions of law. Specifically these are stories that are less about the necessity of anti-fgm law or indeed the necessity of torturing the terrorist, and are more about the fear of law's mutilation of the imagined sovereignty of the democratic subject before liberal law.

The confusions about the mutilations of the liberal subject, in the case of stories of female genital mutilation, are soothed with an image of the violence done to little girls. Similarly, the confusions about the reality of torture's potential cutting of the liberal subject are foreclosed by the imagination of the violence of the terrorist — his inherent badness — and the urgency of the ‘ticking time bomb’. Both these scenes present the viewer with a scene of cutting that exemplifies the reality of law's capacity to cut, if not now, then later; if not later, then elsewhere. But in the rubric of cosmopolitanism and progress, in the context of a universalism of law and human rights, in the condition of a demand for the universalism of the human, these cuts represent the possibility and potentiality of mutilations before law for everyone. And these cuts must be reckoned with. This book is a discussion of the means and methods applied to this reckoning as the aggressions and fantasies that accompany the fear of law's cut. This book is therefore a story of violence and a story of loss.

The fantasy of female genital mutilation

The story of female genital mutilation is represented in liberal discussions of law and violence as a story of loss. This is less the story of the practices of female circumcision, clitoridectomy, circumcision, sunna — or the many other practices that have no English names — as it is the story of the subject, or subjects, imagining the loss. From this perspective it is not self-evident as to what loss means. The stories of legislating against these practices in countries such as England, Australia, Scotland, Ireland, Italy, the United States and Egypt are infused with notions of what loss is: as the loss of desire, the loss of innocence and the loss of the freedoms of a little girl. This story of loss is a political story, a legal story and a psychoanalytic story, that is, it is a story where a number of images convene to produce law as an effort to produce a self-evidence to loss, and an effort to stem the loss announced by an invocation of law's prohibition. The story of female genital mutilation is therefore no innocuous story: someone is being held down, someone is being prohibited and someone is being cut. But the answers to who this someone is, and who is performing the cut, are not so clear, however. The story of legislating against female genital mutilation is a story of questions, precisely the kind of questions which are difficult to ask when presented with images of screaming children, walls covered with blood, and uncaring perpetrators. In this book I suggest that the answers to questions are not as obvious as anti-fgm advocates would have us believe, and they are the very ordinary questions which not only need to accompany initiatives to legislate against female genital mutilation, but need to accompany all law.

The fantasy of female genital mutilation which promotes law's intervention is well illustrated in dubious and not so dubious research, documentaries, best-selling autobiographies, consultation papers, public documents, and in the commentary in most seminars and classrooms dealing with law, human rights and gender in the West. This fantasy is perhaps never quite so well illustrated than in the photographic essay The Day Kadi Lost a Part of Her Life.6 This is a text published internationally and cited as a very important anti-female genital mutilation text.7 It is a beautifully photographed coffee table book,8 readily consumed through its black and white glossy pages.

In this book the authors work hard to cultivate the identification of the readers looking onto the scenes of Kadi. The first half offers scenes of Kadi's life on one particular day: the day. In the many glossy photos in the opening few pages the reader sees Kadi waking, Kadi playing, Kadi working. The book initially elides any foreignness of Kadi's experience by offering her in poses with which a western reader can identify. The opening photographs — as what might be called the ‘before shots’ ’ depict Kadi, as Australian journalist Pamela Bone describes — with ‘flashing white teeth, laughing, unaware’.9 On these pages Kadi wakes, dresses, ‘flirts’, plays and does her daily tasks. Kadi could be any of us as a child, or she could be our child.

In the middle pages of the book the mood changes. The glossy black and white pages turn briefly to enamel red, and the authors introduce the upcoming pages as ‘Ritual of a Sacrifice’. From this moment the images are, at least for this viewer, difficult to look at. But the authors do not spare their viewers. The ceremony is shown from the most intimate angles. The viewer is offered images of the ‘mutilation’ of Kadi through close ups of her genitals, her legs, her tears. Kadi is screaming, bleeding and straining while the reader looks on. K...