![]()

This book assesses the opportunities and barriers for transitions to renewable and low carbon energy as climate change mitigation options in rapidly developing countries, with a focus on China and India. The book first discusses the link between energy, development and climate change (Chapter 1). The book then elaborates the characteristics of energy systems in developing countries and how they are likely to change in the future due to increased economic growth and industrialisation (Chapters 2 and 3). The book also discusses the role that energy modelling can play in assessing low carbon energy transitions for developing countries (Chapter 3).

The book then uses an energy modelling approach to assess how low carbon energy transitions can be achieved in China and India, focusing specifically on China’s power sector (Chapter 4), the economy of Beijing (Chapter 5) and rural Indian households that do not have access to electricity (Chapter 6). The research assesses the environmental, technical, socio-economic and policy implications of these low carbon transitions. The book concludes that low carbon energy transitions can be possible in China and India and that they can considerably contribute to climate change mitigation (Chapter 7).

This book is of interest to scholars, students, practitioners and policy-makers working in the fields of energy and development, energy policy, energy studies and modelling, climate policy, climate change mitigation, climate change and development, low carbon development, sustainable development, environment and development, and environmental management.

Energy is a vital commodity and is closely intertwined with climate change and development. Energy is needed for basic human needs: for cooking, heating, lighting, boiling water and for other household-based activities. Energy is also required to sustain and expand economic processes like agriculture, electricity production, industries, services and transport.

It is commonly suggested that access to energy is closely linked with development and economic growth (e.g. DfID, 2002; IEA, 2002a; WEC, 2000; WEC, 2001; WHO, 2006; WHO/UNDP, 2009; IEA, 2010; SE4All, 2013) and that alleviating energy poverty is a prerequisite to fulfil the Millennium Development Goals (DfID, 2002; WHO, 2006; IEA, 2010; SE4All, 2013). This has been acknowledged in the UN Sustainable Energy for All Initiative (SE4All, 2013), which has the target to provide access to modern energy services to everyone world-wide by 2030 (SE4All, 2013).

There is a link between income levels and energy access. A correlation has been found between rising income levels, both at household level and at national level, and rising energy access.1 This is valid for electricity access and access to modern fuels (World Bank, 2012). Consequently, countries that have higher incomes tend to have higher electricity access rates (Urban and Nordensvärd, 2013).

About 80% of the global primary energy supply comes from fossil fuels, primarily oil and coal (IEA, 2013). Fossil energy resources are limited and fossil energy use is associated with a number of negative environmental effects, most importantly global climate change, and therefore energy has become a major geo-political and socio-economic issue. This development puts pressure on all countries around the world. The pressure on developing countries2 may be even greater, because they are currently in the process of development which requires more energy resources for achieving higher living standards. High population levels and high fossil fuel reliance increase this pressure even more. To meet energy security, reduce pressure on fossil energy resources and to ensure a higher environmental quality, the share of renewable and low carbon energy should be enhanced. The next section discusses how energy use and climate change are linked.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change IPCC (2007a:253) states that “Currently, energy-related GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions, mainly from fossil fuel combustion for heat supply, electricity generation and transport, account for around 70% of total emissions including carbon dioxide, methane and some traces of nitrous oxide”. It is well documented that these emissions contribute to global climate change. Energy use has potentially significant climate impacts, which are assumed to exceed the impacts from other sources like land use and other industrial activities. It is therefore considered crucial to promote greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction technologies for fossil fuel combustion processes. The IPCC states a wide range of global and regional effects of global climate change relevant for this research:

The IPCC states that

The atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, and nitrous oxide have increased to levels unprecedented in at least the last 800,000 years. CO2 concentrations have increased by 40% since pre-industrial times, primarily from fossil fuel emissions and secondarily from net land use change emissions.

IPCC, 2013:7

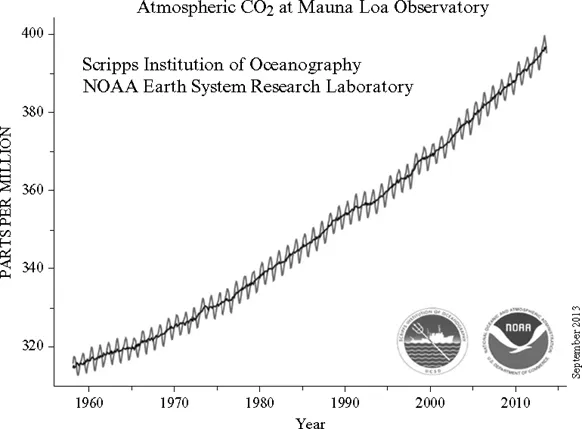

The IPCC has an extremely high confidence level of 95% probability that global climate change is anthropogenic caused due to excessive greenhouse gas emissions (IPCC, 2013). At the global scale, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 has increased from a pre-industrial value of approximately 280 parts per million (ppm) to around 380 ppm in 2005 (IPCC, 2007a; IPCC, 2007b) and a reported peak level of 396 ppm in 2007 (Richardson et al., 2009). In summer 2013 it was reported that the atmospheric concentration of CO2 had surpassed even the 400 ppm level at one stage (Tans and Keeling, 2013). See Figure 1.1 for details.

According to the IPCC (2013), the global mean surface temperature has risen by 0.85°C ±0.2°C between 1880 and 2012 (IPCC, 2013). This increase has been particularly significant over the last 50 years. From a global perspective, the IPCC (2013) reports that they found high increases in heavy precipitation events, while droughts have become more frequent since the 1970s, especially in the (sub)tropics. There are also documentations about changes in the large-scale atmospheric circulation and increases in tropical cyclone activity since the 1970s (IPCC, 2013). The IPCC’s latest Fifth Assessment Report highlights the observed and partly irreversible changes to the earth’s ecosystems, particularly the changes to the oceans, that absorb a large part of the CO2 and thereby become acidified, and the cryosphere (IPCC, 2013).

Today, the majority of climate scientists agree that

Figure 1.1: Atmospheric CO2 concentrations in part per million (ppm) at Mauna Loa Observatory between 1960 and 2013, reported in September 2013

the possibility of staying below the 2 degree Celsius threshold by 2100 between ‘acceptable’ and ‘dangerous’ climate change becomes less likely as no serious global action on climate change is taken (Richardson et al., 2009; Urban, 2009; Urban et al., 2011). A rise above 2 degrees by 2100 is likely to lead to abrupt and irreversible changes (IPCC, 2007c; IPCC, 2013). These changes could cause severe societal, economic and environmental disruptions which could severely threaten international development throughout the 21st century and beyond. (Richardson et al., 2009; Urban, 2010; Urban et al., 2011)

Urban and Nordensvärd, 2013:4.

Climate scientists estimate that for a 50% chance of achieving the 2 degree target, a global atmospheric CO2 equivalent concentration of 400 to 450 ppm should not be exceeded (Richardson et al., 2009; Pye et al., 2010).

To limit global warming to 2 degrees by 2100 will require an immediate reduction in global greenhouse gas emissions and a total reduction of about 60–80% of emissions by 2100 (Richardson et al., 2009). This would require a peaking of global emissions by 2020 or earlier.

Urban and Nordensvärd, 2013:4–5

Nevertheless, the 400 ppm target is reported to have been reached recently (Richardson et al., 2009; Tans and Keeling, 2013) and still emissions are rising. There is therefore a need to reduce emissions rapidly and significantly to avoid dangerous climate change.

Climate change is a serious threat for developing countries, including for the world’s most populous developing countries China and India in Asia. The IPCC (2007c) projects that most Asian regions are likely to warm above the global mean. Only Southeast Asia is expected to warm similarly to the global mean. It is very likely that in East Asia heat waves will be of longer duration, higher intensity and frequency, while there might be fewer very cold days in East and South Asia. Precipitation is likely to increase in most regions in Asia, but is projected to decrease in Central Asia. It is very likely that there will be increases in the frequency of intense precipitation events in parts of South Asia and in East Asia (IPCC, 2007c). The IPCC (2007c) further assumes that there will be increases in extreme rainfall and extreme wind due to tropical cyclones in East, Southeast and South Asia. It is possible that monsoon flows and large-scale tropical circulations might be weakened (IPCC, 2007c).

Global climate change is already an observed phenomenon today. Strategies for climate change mitigation, as under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Kyoto Protocol, are necessary on a global scale, particularly for high GHG emitters like the industrialised countries, countries in transition and emerging economies. Strategies for climate change adaptation – strategies of how to live with and adapt to climate change – are of an equal global importance. These adaptation strategies are especially needed for the poorest and most vulnerable developing countries, which suffer from the impacts of climate change without even significantly contributing to it. Unlike industrialised countries, many developing countries often do not have the financial, infrastructural or administrative resources to adapt to and mitigate climate change (IPCC, 2007c). It should therefore be a global priority to promote and support climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in developing countries. Especially the industrialised Northern countries, which are historically considered responsible for about three quarters of accumulated emissions and therefore the bulk of global climate change (WRI, 2005), should have the responsibility to assist their poorer neighbours in the global South.

Energy use is not only likely to contribute to global climate change, but also gives rise to other negative impacts. One of the possible impacts of energy use is local air pollution, which has been a serious problem in the world’s mega-cities for decades and is linked to fossil fuel combustion. Health problems linked to local air pollution, such as lung cancer and chronic respiratory diseases, are a serious problem. These diseases also result in high cost burdens to the world’s health systems (WHO, 2000 and WHO, 2005). Other possible impacts of energy use are the exploitation of finite resources, the destruction of nature, landscapes and biodiversity for energy resources, the need for energy imports, and struggles for energy security, which sometimes even result in geo-political conflicts and wars. Energy use further involves high externalities: the costs for environmental and health damages which individuals, institutions and governments have to pay as a consequence of energy consumption.

All these impacts demonstrate how meaningful low carbon energy transitions could be especially for developing countries. The next section discusses the development process and how this relates to the current climate change debate and issues of equity and fairness.

The development of mankind dates back thousands of years. Even though humans have always exploited nature in some way or other, this development only became excessively unsustainable during the last two centuries. Many of today’s global climate change problems and other environmental problems are assumed to be due to the increased consumption and production of industrialised countries starting with the Industrial Revolution in the late eighteen th century. This process is still continuing today as developed countries are characterised by industrialisation, high levels of consumption and production, and unsustainable development patterns.

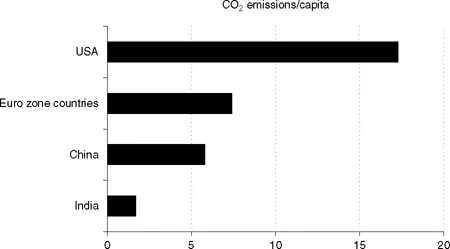

Figure 1.2: Per capita CO2 emissions for the US, the European Monetary Union, China and India in 2010

Developing countries have only recently begun to industrialise. Emerging economies like China and India developed within a few decades from relatively modest users of energy to some of the world’s major consumers of energy and natural resources. Recently, they also became significant emitters of GHG measured in absolute terms. Since 2007, China has overtaken the United States (US) as the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gas emissions in absolute terms. India is currently ranked in the global top five in terms of the world’s largest emitters of greenhouse gas emissions in absolute terms (IEA, 2013). The current per capita contribution of emerging economies to climate change is however much lower than the per capita contribution of industrialised countries. In 2009, the average Indian emitted only 1.7 t CO2 per capita, compared to the average Chinese who emitted 5.8 t CO2 per capita, while the average US American emitted 17.3 t CO2 per capita. This means that the average Indian emitted almost 10 times less CO2 per capita than the ave...