![]() Part I

Part I

Technical and policy options![]()

1

Overview

The purpose of this book is to provide government and industry policymakers, scientists, and engineers with an understanding of the technical and policy options available for managing variable energy resources such as wind and solar power to produce electricity. The text is informed by knowledge gained during Carnegie Mellon University’s RenewElec (short for renewable electricity) project that began in 2010, based on years of preceding work.

Renewable energy resources tend to have variable output power on several time scales. Hydroelectric power’s production, for example, varies by season. On longer time scales, it is lower in drought years and greater in wet years. Wind power varies on time scales of seconds to years. Solar power and geothermal power are also variable. The U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) calls such generators “variable energy resources” (VER).

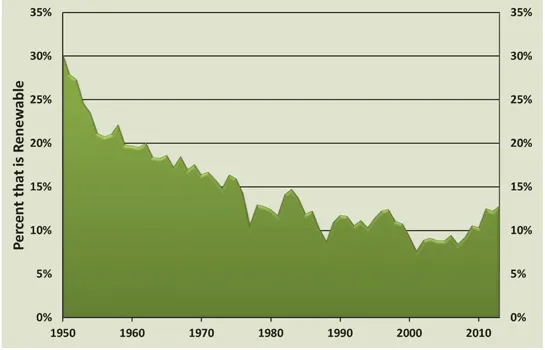

Renewable energy as a source for electricity generation in the United States fell from 30% in 1950 to a low of 8% in 2001, as the market share of hydroelectric power was eroded by fossil fuel generators built to keep up with the rapidly increasing demand for electricity (Figure 1.1). Even though hydroelectric generation tripled between 1950 and 1973, demand for electricity increased nearly six-fold. By 2013, renewables’ market share had increased to 13%, primarily due to policies that encouraged an increase in wind power’s contribution.

A significantly expanded role for variable energy resources can be achieved. It is likely that renewables can regain or exceed the share of electric power they represented in 1950. In order to do this, the United States should adopt a systems approach that considers and anticipates the changes in power system design and operations that will be required while doing so at an affordable price and with acceptable levels of security and reliability.

FIGURE 1.1 Market share of renewable electric power generation, including hydroelectric power, in the United States from 1950–2013 (EIA, 2014).

The RenewElec project1 was created as an interdisciplinary project led by Carnegie Mellon University to facilitate dramatic increases in the use of electric generation from variable sources of renewable power in a way that:

- Is cost-effective

- Provides reliable electricity supply with a socially acceptable level of local or large-scale outages

- Allows a smooth transition using the architecture and operation of the present power system

- Allows and supports competitive markets with equitable rate structures

- Is environmentally benign

- Is socially equitable.

This book, based on empirical evidence and research by our PhD students and faculty, provides a summary of major challenges and opportunities for integrating variable power generation sources and meeting the goals set forward in the state renewable portfolio standards.

In this chapter, we describe renewable electricity and provide information on renewable electricity’s current and potential contribution to electricity generation. We also describe the national and state policies currently in place that influence renewable electricity’s contribution to the electricity grid, as well as the major challenges and opportunities it faces in doing so. Last, we provide an overview of the remainder of this book.

1.1 What is renewable electricity?

Renewable electricity is generally defined as derived from any energy resource that is theoretically inexhaustible in periods of interest to humans and is thus constantly replenished on time scales of days to decades. Renewable electricity can be derived directly from the sun, such as thermal, photoelectric, and photochemical energy; indirectly from the sun, such as hydroelectric, wind, and photosynthetic energy stored in biomass; or from natural processes in the environment, such as geothermal and tidal energy. Renewable power sources generally have lower environmental damages than coal, natural gas, and oil power, particularly lower emissions of conventional air pollutants and greenhouse gases. However, these resources are not entirely free of environmental externalities. Large hydropower reservoirs, for example, are a source of methane emissions that contribute to climate change, and land-use changes caused by many power generators are a source of environmental concern.

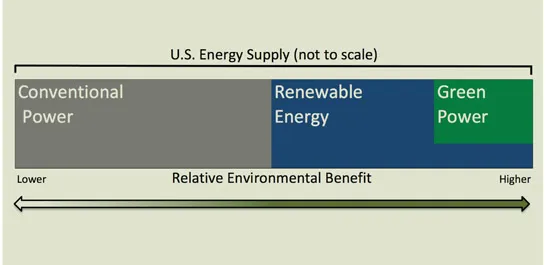

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines a further subset of renewable power as green power, which consists of resources that do not directly emit greenhouse gas. These green power sources include wind, solar, geothermal, and biomass. Figure 1.2 shows a schematic of the different power source classifications described by the EPA.

FIGURE 1.2 Classification of power sources (redrawn from EPA, 2010).

1.2 What is renewable electricity’s current contribution to electricity generation?

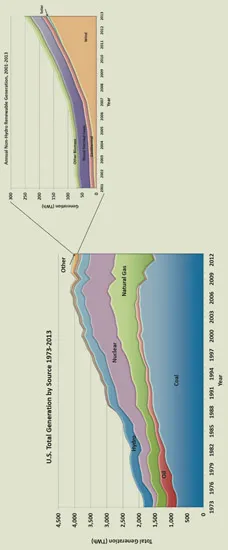

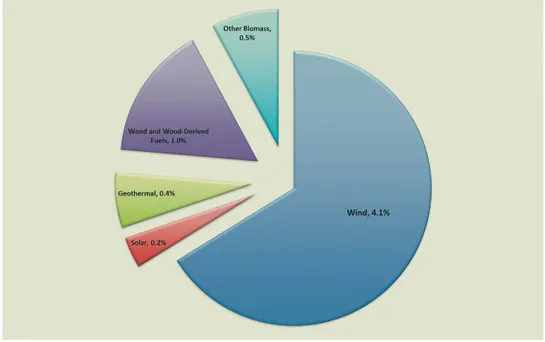

Renewable energy as a source for electricity generation is increasing at a rapid rate in the Unites States and elsewhere. In 2008, renewables, including hydroelectric power, constituted only about 9% of all U.S. electricity generation (see Figure 1.3). By 2013, the share had increased to 12.9%, primarily due to an increase in wind power’s contribution (see Figure 1.4).

1.3 Why has renewable electricity grown in the United States?

Two policy changes at the state and national levels have led to the rapid increase of renewable energy: renewable portfolio standards (RPSs) at the state level and federal tax credits. The latter include the production tax credit (PTC) used primarily by wind developers and investment tax credit (ITC) used primarily by solar developers.

Although there is no U.S. national renewable energy standard, 29 states and the District of Columbia have RPSs requiring that some percentage of their electric power come from sources defined as renewable (DSIRE, 2011). The language in state RPSs can vary significantly, and while some states have a single (primary) standard, some states have several types. Colorado, for example, has a primary standard that applies to investor-owned utilities and a secondary standard that applies to electric cooperatives (DSIRE, 2011). Similarly, some states have “setasides” that require that certain technologies be used to meet a given RPS level. Figure 1.5 shows the primary RPS requirements and solar set-asides that apply to large investor-owned utilities, as well as the target year for the final target.

In the United States, three major constituencies have advocated for growth in sources of renewable energy and energy efficiency measures, including an:

- Environmentalist constituency worried about fossil fuels’ contribution to climate change and pollution

- Energy security constituency worried about the national security and the need to reduce dependence on foreign fossil fuels, limit demand, and lower cost (Pew Charitable Trusts, 2012; U.S. DOD, 2012)

- Economic vitality constituency that is worried that high energy prices, market volatility, and disruptions to the energy supply will threaten the national economy and result in lost jobs (Long, 2008).

A detailed discussion of the economic rationale for the policies adopted by various governments is not the focus of this book; however, we now provide a brief discussion of the different mechanisms that are available to policy makers. Generation of electric power produces not only electricity but also pollutants that enter the environment, both during the manufacturing of the generator and during its operation. Economists call these costs “externalities.” For conventional pollutants, these costs

FIGURE 1.3 (a) Total U.S. electricity generation by source, 1973–2013, and (b) nonhydroelectric renewable electricity generation by source, 2001–2013 (EIA, 2014).

can be estimated by observing the human health effects. Such estimates for greenhouse gas pollution are quite uncertain in magnitude and timing (see Chapter 7).

FIGURE 1.4 2013 U.S. nonhydro renewable generation by source. Values represent the percentage contribution of each resource to total generation (EIA, 2014).

If the costs of this pollution are not included in the price of electricity, an economist would say that the artificially low prices cause customers to consume more power than the economically efficient amount. A number of jurisdictions forbid some of the pollution (command-and-control regulation). Economists realized that this sort of regulation can lead to retiring a generator before its useful life is reached, and so cap-and-trade regulations have been instituted (notably for nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide [NOx] emissions) to allow the pollution from older plants to be offset by newer and cleaner plants.

A few jurisdictions (for example, the United Kingdom for a time) levied a pollution fee on all electric power sold, encouraging less use and thus less pollution. Other jurisdictions have subsidized the introduction of low-polluting power (for example, with a PTC, ITC, or feed-in tariff) by an amount that is roughly equal to the externality costs. While this policy reduces pollution, its costs are borne by the taxpayers rather than by the users of electricity, and economists object that thus the price of power is being artificially reduced, leading to overconsumption.

An RPS, like command-and-control regulation, both lowers pollution and has costs that are borne by the electricity consumer, encouraging use of an economically efficient amount of electric power.

However, an RPS may not be efficient if the power sources inc...