- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Foundations of Geometry and Induction

About this book

This is Volume of IV eight on a series on the Philosophy of Logic and Mathematics. Originally published in 1930, this study contains sections on geometry in the sensible world and the logical problem of induction.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Foundations of Geometry and Induction by Jean Nicod in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

GEOMETRIC ORDER

CHAPTER I

PURE GEOMETRY IS AN EXERCISE IN LOGIC

WHAT then is geometry considered as purely formal? It is whatever we can know about its structure without knowing its object; whatever we can understand in a treatise on geometry without being acquainted with the nature of the entities which it discusses.

In Kant’s time, this point of view had not yet been reached. For geometry, which since Euclid was tending to liberate its proofs from the matter furnished by figures, for the purpose of basing them only on pure reason, had not yet succeeded in doing so. Deprived of concrete diagrams, its proofs seemed without force; the very concatenation of the propositions seemed to belong to these figures and not to the purely logical relations involved. All geometrical knowledge was in this way conceived as inseparable from the apprehension of space—a primitive matter, which, by imparting next its order to the sensible world, played with regard to the latter, the contrary rôle of a form. Thus the imperfect character and peculiar nature of the demonstrations of geometers supplied philosophers with the impression of a special mystery, and committed them to involved theories designed to account for the alleged existence of proofs which did not draw their force from common logic.

But the actual progress of geometrical science allows us to conceive the problem more simply. Indeed, while the philosophers were speculating over the extra-rational character of geometrical proof, the geometers succeeded in doing away with it altogether. They made it a principle that proof by figures is only the outline of a proof. They regarded the appeal to intuition as the index of a lacuna, the sign of the use of an assumed principle which they tried to make explicit; they would not accept any proof as regular unless it formed an entirely formal chain.

To obtain a proof, in this state of formal perfection, it is no longer necessary to illustrate it by a figure, to relate it to a matter, to attribute a determinate meaning to the geometrical expressions which it involves, for these concrete values add nothing to its force. It is possible to be convinced that the theorems flow from the axioms and postulates without knowing the meaning of a point, a straight line or distance; there is not a geometer today who would deny this. By becoming rigorous, that is to say explicit, geometrical proof has detached itself from all objects.

We do not have here any paradoxical development. Quite on the contrary, it puts an end to the paradox which opposes geometrical reasoning to all other reasoning. For a good demonstration, stated without anything implicit, is valuable for its form alone, independently of the truth and even of the meaning of its system of propositions. We may be astonished at this important fact, but we cannot doubt it. By freeing itself from all figures, by detaching itself from the meaning of the material terms which figure in it, geometrical demonstration has simply returned to common reason.

It is then possible today, as it was not a century ago, to take a completely abstract and fundamental view of geometrical science as independent of any object. It then appears as a chain of formal reasoning, which is in a certain sense blind, and which draws consequences from a group of premises formulated in terms of entities whose meanings, indifferent to the argument, remain quite indeterminate. Such is the universality of geometry. It is under this form, devoid still of any reality, that it may be fixed in our minds now. For, by conceiving it, at first, disengaged from any object, we are prepared to discern without any preconceived idea the objects of the universe to which the science is in fact applied.

Suppose then that we have not been taught geometry in school, and that we are acquainted with none of the particular terms of that science. Undoubtedly, the very things with which it is commonly supposed to deal, cannot fail to be familiar to us. But let us suppose that nobody has ever taught us their scientific names, and that, like the child Pascal, we call a straight line a bar and a circle a ring. Let us imagine that someone puts in our hands one of those treatises on geometry which aim only at rigour and which disdain all figures. What shall we get from it? Let us try, however, to read it.

It is composed of a small number of initial statements entitled “axioms” or “postulates” and other propositions entitled “theorems,” which appear to spring from the first by virtue of texts entitled “demonstrations.” But if we understand the terms of current language only, and in particular the terms of ordinary logic, all the properly geometrical terms such as “point,” “straight line,” “distance,” are entirely unknown to us; and these new terms seem to us at first very numerous. However we soon notice that they are for the most part introduced as simple abbreviations of complex expressions, in which we find only a small number of unknown terms. The latter are always identical, and must be only those contained in the initial propositions. There will be, for example, the class of “points,” the relation of three points “in a straight line,” and the relation of two couples of points “separated by the same distance”; thus, the term “sphere” will be defined as the abbreviation of the complex expression “class of points separated from a certain point by a constant distance.”

We have taken inventory of the unknown expressions and we have reduced them to three. However, we have not eliminated them; since we are not aware of any subsistent expressions, we must admit that we do not understand what the “axioms,” “postulates,” “theorems” mean. But, to our surprise, we understand perfectly the intermediary steps called “demonstrations.” The terms which embarrass us are still to be found there, but it is enough for us to understand the ordinary words which accompany them, and which belong to the logical sheathing of language, in order to follow the argument step by step, to grasp its march, to enjoy its ingenuity, and to discern its precision.

There is something surprising in this fact that the rigour or force of a demonstration can be apprehended without any knowledge of its matter. We are astonished to be able to proceed thus with our eyes closed. But this very force of form is found again in the most simple reasoning, and is valid in any given case because it holds for all possible and impossible cases. That is the constitutive fact of logic, remarkable, certainly, but common.

Then what do we learn from our reading? We may answer by saying: “I do not know what the author of this treatise calls a point, nor a fortiori what he calls three points in a straight line and two couples of points separated by a constant distance. But I know that if these three things really have, as he asserts, the properties that the axioms and postulates state, they cannot tail to have at the same time all the properties that the theorems state.”

Reflecting on the fact that we have been able to establish the connection which links the various propositions in which these three terms with unassigned meanings figure, we can rise even to a more general view-point. Instead of assigning to these terms determinate but unknown meanings, we can take them as variables—a symbolic means of expressing this universal truth: “if a class π, a relation R having as terms three members of π, and a relation S having as terms two couples of members of π satisfy the axioms and postulates—in other words—if the assignment of three meanings π, R, S to the three expressions point, in a straight line, separated by a constant distance, transforms the axioms and postulates into true assertions—the meanings π, R, S also satisfy the theorems.”

A geometrical proposition ceases then to be determinate and susceptible of being true or false by itself. It is no more than a formula with blanks to be filled by all kinds of different propositions, some false, others true, according to the meanings attributed to its variables: it is only a propositional function; and the systematic implication, for all meanings, of the propositional functions that are theorems as derived from the propositional functions that are axioms and postulates* forms all the instruction that we can obtain, in our ignorance, from the geometrical treatise which fell into our hands.

Let us close the treatise now and ask ourselves what motives could have impelled its author to write it. Perhaps it was the unique charm of the logical adventure, the singular pleasure of deducing the implications of a group of propositions chosen—like the rules of games of mental entertainment—for the sake of the diversity and harmony of their consequences. Perhaps, on the contrary, the author has tried to imitate nature by making axioms in accordance with natural objects. Has he not modelled his axioms on the demonstrated or conjectural properties of certain entities which are found in his universe, and perhaps also in ours? Let us try then to discover, or at least to conceive one or more systems of meanings satisfying the axioms of our author: we shall say that such a system of meanings is a solution of this group of axioms.

The domain of numbers furnishes an answer first. Let us in fact attribute these meanings:

(1) to the variable class of points, the class of ordered triads of real numbers taken with their signs;

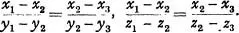

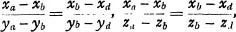

(2) to the variable relation in a straight line, the relation of three triads of real numbers (x1, y1, z1), (x2, y2, z2), (x3, y3, z3), expressed by the equations

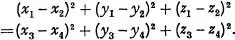

(3) To the variable relation separated by a constant distance, the relation of two couples of trios of real numbers (x1, y1, z1), (x2, y2, z2); (x3, y3, z3), (x4, y4, z4) expressed by the equation

It is known that the system of meanings (1), (2), (3), satisfies the axioms of Euclidean geometry.

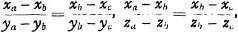

This geometry admits then of one interpretation or purely arithmetic “solution.” However, abstract geometry being more often confounded with its application to a particular interpretation called “space,” the arithmetic interpretation is commonly introduced under the indirect form of a measure of space. But this detour is superfluous. As soon as geometry is conceived by itself as a form devoid of all application, it is seen that this scheme is applicable directly to numbers without any necessity of regarding them as measures or representations of a determinate subject matter. It is by thus substituting the purely arithmetic meanings (1), (2), and (3) for points, rectilinearity, and congruence, that the axioms, and consequently the theorems are resolved into arithmetical propositions. For example, the axiom which says that if the points a, b, c are in a straight line, and if the points b, c, d are also in a straight line, then the points a, b, d are in a straight line becomes in this interpretation: If the numbers xa, ya, za; xb, yb, zb; xc, yc, zc have the relation

and if the numbers xb, yb, zb; xc, yc, zc; xd, yd, zd have the relation

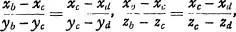

then the numbers xa, ya, za; xb, yb, zb; xd, yd, zd will have the relation

which is in fact an arithmetical theorem.

It is true that these arithmetical meanings of the primitive expressions in our treatise on geometry are not simple, and that being complex, they seem all the more artificial. Is it not strange that a point can be a class of three numbers? Not at all, since “point” is, prior to such a class definition, an empty word.

The discovery of one system of meanings satisfying a group of axioms is always logically very important: it constitutes the proof that these axioms do not contradict one another; and this is the only known proof of consistency. So arithmetic is one guarantee of the compatibility of the axioms of geometry. But there are perhaps, outside the domain of numbers, other “solutions” for this same group of axioms: it is the search for these that constitutes the object of this work.

* The difference between a postulate and an axiom is only a matter of degree in regard to evidence, and does not exist for us because both, deprived of any fixed meaning, lack altogether any self-evidence. We shall then call axioms all the premises of a treatise on geometry in order to simplify language. Such is, besides, the usage of several modern geometers.

CHAPTER II

FORMAL RELATIONSHIP OF VARIOUS SYSTEMS OF GEOMETRY

WE might conclude our intr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE BY BERTRAND RUSSELL

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I GEOMETRIC ORDER

- PART II TERMS AND RELATIONS

- PART III SOME OBJECTIVE GEOMETRIES

- SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

- INDEX