![]()

1 Neighborhood associations in Japan’s civil society

1 Introduction

Neighborhood associations (NHAs) are found in many countries throughout the world, but Japan distinguishes itself through its nationwide blanketing by the organizations (about 300,000 across Japan) and by the high rates at which citizens participate in the groups. By any measure, NHAs as a group are the biggest civil society organization in Japan: they have the most organizations, the most members, and attract the greatest participation. In addition to their size, Japanese NHAs have drawn attention from scholars because of their “ambiguous” nature that “straddles” the boundary of state and society (Pekkanen and Read, 2003; Read and Pekkanen, 2009; Read, 2012). Besides the interest from students of civil society, we argue here that NHAs should command attention from anyone interested in governance at the local level. Indeed, much of this book makes the argument that NHAs contribute to local governance in five specific ways. Unfortunately, our understanding of NHAs has been limited, because scholars lacked detailed nation-wide information about the groups. In this book, we are able to draw from the first ever detailed nationwide survey of NHAs in order to shed light on many aspects of NHAs.

1.1 Defining NHAs

Before we go any further with our analysis, we need to pause and define neighborhood associations. Japan’s NHAs are in some ways easier to talk about in English than in Japanese. This is simply because, as we detail in Chapter 2, there are many different local terms for “neighborhood association” in Japanese, whereas the English term is somewhat more standard. In any event, in this book, we follow the definition set out by Pekkanen (2006).

Neighborhood associations are voluntary groups whose membership is drawn from a small, geographically delimited, and exclusive residential area (a neighborhood) and whose activities are multiple and are centered on that same area.

(Pekkanen, 2006: 87)

“Multiple” activities may sound vague, but we spend Chapters 4 through 8 going into more detail. For now, let us only say that these activities include maintaining the local environment, social events among the residents, safety and welfare activities, cooperation with local government through disseminating information among residents, and articulation of local demands to government. We discuss the scale of NHAs in more detail in Chapter 2, but the median size of NHAs is about 100 households. Although not part of the above definition, NHAs have a few other related characteristics we want to stress at this early point. First, NHAs in Japan are also always open to membership by all neighbors (Nakamura, 1964; Iwasaki, 1989; Torigoe, 1994; Kurasawa, 2002). In fancier words, they maintain the principle of universal membership. Because of this, NHAs typically present themselves as the representative organization of the neighborhood (Nakata, 1996). Second, Japanese NHAs enjoy a monopoly (Torigoe, 1994; Kurasawa, 2002; Pekkanen, 2006). Part of this is just an explication of “exclusive.” In Japan, the boundaries of NHAs are clear and do not overlap. Moreover, there is no competition at the margin for membership. Of course, neighbors don’t always get along in Japan, like anywhere else. So, it may strike the reader as curious not to find examples of rival NHAs competing for membership in the neighborhood. (Instead of splintering, disgruntled NHA members are likely to simply drop out.) In addition to being clear about their boundaries and not competing with other NHAs for membership, we also find that in any given neighborhood there is only one NHA (so, no one in Japan needs ever to wonder about which NHA to join). NHAs undoubtedly owe their monopolistic status to the legitimation they enjoy from their privileged relationship with the state, called for that reason by Pekkanen (2005, 2006) Japan’s “local corporatism” (see also Read, 2012). For a capsule portrait of NHAs, readers may also refer to Section 2 of Chapter 9 (“A Profile of Japan’s Neighborhood Associations”).

2 NHAs and civil society

Debates about the definition of civil society have raged on for many years in the academic community. The study of NHAs has something to contribute to these discussions. We believe that the nature of NHAs calls attention to how civil society can be structured by the state, flourish through state promotion, and contribute to social capital (Pekkanen, 2003, 2006). However, the focus of this book is empirical. We adopt a definition of civil society that focuses on organizations: civil society is the organized, non-state, non-market sector.1

NHAs clearly fit into these boundaries, and we consider them to be part of civil society. Arguments against their inclusion could focus on the voluntariness of membership or their relationship with the state. Let us address these in turn. Certainly many NHAs rely on social pressure to get neighbors to join. This emphasis on enmeshing the individual in a web of obligations, and the emphasis on the group, contributes to the view that NHAs’ prevalence and longevity have something to do with their cultural fit in Japanese society. It is worth underlining that there is no coercion or force, either by neighbors or by the state, for individuals to join NHAs. No citizen of Japan is required to join any NHA. If we exclude organizations which people join in order to keep neighbors or friends happy, then it is not just NHAs that are in danger of being struck from the list, but churches, environmental groups, and many others. The relationship between NHAs and the state involves state financial support and legitimation. In receiving financial support, however, NHAs are not different from many civil society groups around the world, including those thought of as quintessential civil society groups. Legitimation is a more important resource, probably, for NHAs. In our judgment, however, the provision of this resource alone does not disqualify NHAs from being considered part of civil society. The weight of the evidence shows NHAs to be independent from state control. As we show in Chapter 8, NHAs engage in an exchange relationship with the state, trading support for policy implementation in exchange for demands being met. NHAs are not mere cheap subcontractors for the state, but engage in a complex mutualistic relationship central to local governance. Moreover, NHAs get most of their budget from membership fees, not from state support, as we show in Chapter 2. They are also independent in their selection of leaders, as we show in Chapter 3. And, activities focused on the community and community events, not cooperation with the local government, are the self-identified core mission of most NHAs (see Chapter 4).2

2.1 Context of Japan’s civil society

In recent years, a number of authors have provided overviews of Japan’s civil society (Yamamoto, 1995; Tsujinaka, 2002b; Schwartz and Pharr, 2003; Pekkanen, 2006; Kawato et al., 2011; Kawato, Pekkanen and Yamamoto, forthcoming) or nonprofit sector (Yamamoto, 1998; Yamauchi, 1999, 2000). Different authors use varying understandings of civil society, of course. However, a common theme that stands out is the relative weakness of Japan’s civil society, when understood as advocacy groups, NGOs (non-governmental organizations), or NPOs (non-profit organizations).3 The exceptions are the economic organizations, which can be quite sizeable and influential (Tsujinaka, 2003).

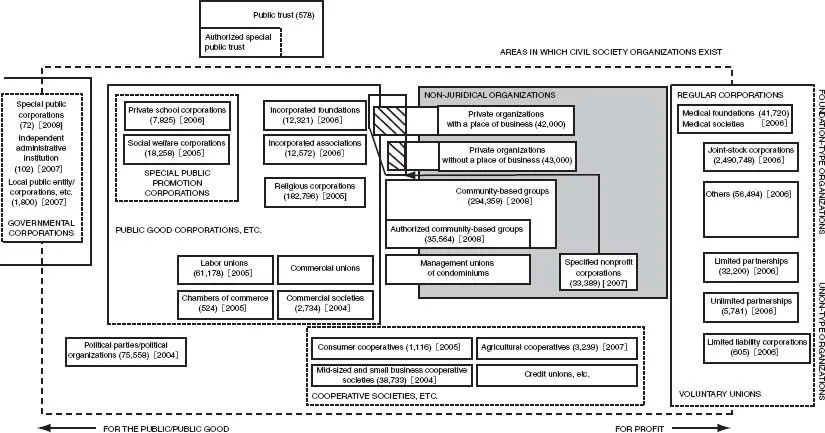

Figure 1.1 provides an overview of Japan’s civil society landscape, depicting the organizations that inhabit the terrain. We provide this heuristically, in order to situate NHAs in Japan’s civil society. We have distributed organizations conceptually to some degree. Bold dash lines show the sphere in which civil society organizations exist.4 The horizontal axis distributes groups on the basis of “publicness.” Towards the left of the diagram are groups that serve the public interest, whereas the ones on the right serve private interests. The vertical axis is for legal status. Moreover, the bold lines represent the concept of legal status and the narrow dotted lines represent the concept of tax status.

There are more than 800,000 of these organizations throughout Japan (803,519, to be exact). Of these, there are 294,359 NHAs as discussed within this book. This total includes some 35,564 organizations that have obtained legal status as authorized local area groups (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, 2008). This makes NHAs the largest single type of group populating Japan’s civil society.

Figure 1.1 Japanese civil society organizations (2004–2008).

Note: Groups and organizations are positioned on the basis of the National Institute for Research Advancement’s Report No. 980034, Research Report on the Support System for Citizens’ Public-Interest Activities (in Japanese), 1994, 27. The number of organizations has been supplemented by the author using government statistics. Numbers from 2007 and recent years are included. The shaded area on the central right side of the figure represents the area where institutionalization is incomplete, with organizations lacking any legal status.

Source: Based on and updated from Tsujinaka and Mori, 1998.

In this context, NHAs stand out as exceptional. As we noted above, NHAs are very widespread and enjoy high levels of participation and membership. Pekkanen (2006) argues that both the weakness of Japan’s advocacy sector and the strength of its NHAs can be traced to institutional arrangements, while Haddad’s (2007) international comparison finds the source in society, and Avenell’s (2010) research directs us to examine ideational factors. Pekkanen argues that while overall there are many small-scale organizations active on the local level, there remain few organizations that employ full-time staffers and influence policy decision-making (Pekkanen, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006). Thus, he uses the phrase “membership without advocacy” to describe this characteristic (Pekkanen, 2006: 20).5 That is to say, while Japan’s civil society structures foster social capital and support democracy through the maintenance of the community, their influence does not extend to the functioning of the public sector and policy determination. As such, Pekkanen asserts that one feature of civil society in Japan is the strength of state influence on civil society structures. In Japan, acquiring legal status is difficult and those that have acquired such status are strictly regulated. In addition, even when compared to other advanced democratic countries, civil society structures do not enjoy preferential tax treatment. Such regulatory conventions have prevented the growth of groups that have the ability to provide policy recommendations.

The “strength” of the government with regard to civil society in Japan in this manner also has been described as a feature of Japan’s bureaucracy, characterized as a “maximum mobilization system” (Muramatsu, 1994). However, such maximum mobilization may also be ascribed to “weakness” in government. Maximum mobilization is a system that utilizes social resources available to the bureaucracy as efficiently as possible, and thus, form networks that include civil society structures and implement the undertakings proposed by the bureaucracy. In terms of the size of the state – the number of public employees, budget size relative to the economy – the Japanese state may appear quite small in international perspective. However, Muramatsu (1994) argues that this mobilization allows it to achieve policy goals despite the small size. As a result, however, the boundaries between government and civil society structures are blurred (Itō, 1980; Takechi, 1996), and the government retains a powerful position vis-à-vis civil society (Takechi, 1996; Yamamoto, 1998; Pharr, 2003; Ogawa, 2009).

2.2 “Straddlers” and civil society

Arguments about state domination of NHAs have also circulated (Matsushita, 1961; Akimoto, 1971, 1990; Matsuno, 2004, among others). As we discuss in Chapter 2, there was a period of state control over NHAs and some progressive Japanese mistrust this historical legacy. However, in international perspective, Japan’s NHAs exhibit fairly weak state influence (Pekkanen and Read, 2003). Pekkanen and Read (2003) provide a useful intellectual framework when they argue that certain types of civil society structures are “straddling civil society” and acting as a type of administrative intermediary form of civil society organization. These groups are based in society, but they also are characterized by collaboration with government in the smooth implementation of policy and articulation of local demands. Japan’s NHAs are by no means the only “straddlers” in the world. We see other examples in Indonesia, Singapore, South Korea, and elsewhere (Pekkanen and Read, 2003; Read and Pekkanen, 2009; Read, 2012). However, Japanese NHAs are quintessential examples of these administrative intermediary civil society groups. In fact, what we demonstrate in this book is that NHAs are intermediaries. They are not subservient to the state, but engage in an exchange relationship with it (Chapters 7 and 8). Although NHAs do engage in active cooperation with lo...