- 282 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Progress in Urban Geography (Routledge Revivals)

About this book

A substantial proportion of the world's population now live in towns and cities, so it is not surprising that urban geography has emerged as a major focus for research. This edited collection, first published in 1983, is concerned with the effects on the city of a wide range of economic, social and political processes, including pollution, housing, health and finance. With a detailed introduction to the themes and developments under discussion written by Michael Pacione, this comprehensive work provides an essential overview for scholars and students of urban geography and planning.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Progress in Urban Geography (Routledge Revivals) by Michael Pacione in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Housing

D.A. Kirby

Introduction

According to Robson (1979, p. 67) "'the housing problem has only come within the purview of geography very recently'. While the validity of this view is open to debate, it is certainly true that until the early 1970s, housing was a much neglected aspect of urban geography. Apart from a small number of statistical analyses of particular issues (Hartman and Hook, 1956), early studies tended to be either descriptive examinations of the different types of housing (Fuson, 1964) or studies in which housing featured as an important but secondary issue, the main concern being either the study of urban structure (Jones, 1961; Robson, 1966) or the study of transport patterns (Kain, 1962; Getis, 1969). The former approach was followed mainly by the cultural geographers of the period for whom, as Wagner (1969) has observed, housing held a double fascination by contributing (as the studies by Smailes, 1955 and Conzen, 1960, emphasised, for example), to the distinctive character of landscapes and standing as 'the concrete expressions of a complex interaction among cultural skills and norms, climatic conditions, and the potentialities of natural materials'. Invariably such approaches failed to generate universal laws and theories (Garrison, 1962) and with the advent of the 'new' geography of the 1960s, gradually faded from the forefront of geographical enquiry, although some interesting examples were produced at the end of the decade (Whitehand, 1967; Rapoport, 1969; Grimshaw et al., 1970). In contrast, the latter approach, based on the seminal works of Burgess (1924) and Hoyt (1939), was more characteristic of the nomothetic viewpoint and reflected the geographer's increasing concern with space, spatial relationships and spatial patterns. Despite such studies, housing remained a relatively under-researched area of geographical enquiry with no particular focus to the studies which sporadically emerged, though a series of articles by British urban geographers at the turn of the decade was to herald a shift in geographical interest in, and awareness of, the housing question (Blowers, 1970; Spencer, 1970; Drakakis-Smith, 1971; Kirby, 1971).

Even so, by the mid 1970s, geography could be fairly criticised for 'never having concerned itself deeply with the question of housing' (Kirby, 1976, p. 2). From the late 1960s in America and early 1970s in Britain and Western Europe, however, there had been increasing concern over the preoccupation of society with economic issues and efficiency and the lack of concern for social welfare and equity. Within geography, it resulted in the now well-documented, radical or relevance revolution (Castells, 1977; Harvey, 1973; Peet, 1977 and Smith, 1977) and a shift in the objects, objectives and methods of geographical enquiry. As Kasperson observed in 1971 (p. 13),

The shift in the objects of study in geography from supermarkets and highways to poverty and racism has already begun, and we can expect it to continue, for the goals of geography are changing. The new men see the objective of geography as the same as that for medicine — to postpone death and reduce suffering.

As a result of such developments in the subject, geographical interest in housing has increased considerably and by the beginning of the 1980s the vast volume of literature being generated from housing research in geography departments throughout the western world made it possible for a geography of housing to be identified (Bourne, 1981).

While very different from earlier studies of housing and residential geography, there is no uniform approach, as Bassett and Short (1980) have recognised. In part this results from the diversity of social theories upon which the studies have been based and most notably from the distinction between Marxist and non-Marxist doctrines. However, it also results from the very complexity of the subject matter. As Bassett and Short (1980, pp. 1-2) point out

Housing is a heterogeneous, durable and essential consumer good; an indirect indicator of status and income differences between consumers; a map of social relations within the city; an important facet of residential structure; a source of bargaining and conflict between various power groupings and a source of profit to different institutions and agents involved in the production, consumption and exchange of housing.

If anything, housing is even more than this and because of the complicated interrelationships which exist between housing and its environment (however defined) it is understandable, perhaps, that its study is both complex and varied.

Approaches

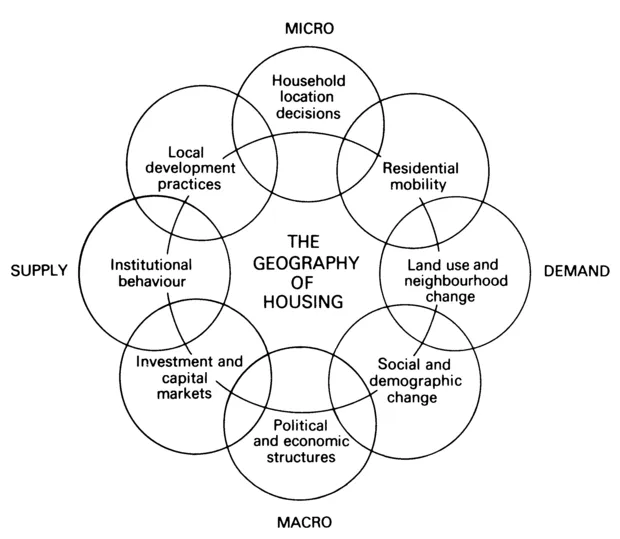

As there is no uniform approach to the study of housing, so there is no uniform agreement over the broad approaches which have been followed. For instance Bourne identifies eight distinct but overlapping areas of research (Figure 1.1) which 'vary in scale (macro, micro) and in subject matter (demand, supply, policy) as well as in their philosophy and methodology' (Bourne. 1981, p. 10). In contrast Robson (1969, p. 71) suggests that, in addition to the micro economic approaches of economists such as Evans (1973), Ball and Kirwan (1975) or Whitehead (1975), three major research foci can be recognised. These, he suggests, are social ecology, conflict theory and managerialism, and Marxist concepts. Like Bourne, however, he argues that these separate strands have overlapped and the work

while having proceeded from different origins, has tended to point in similar directions: by emphasising the importance of constraints rather than choice in access to housing: by illustrating the role of conflict rather than consensus in the goals and interests of the groups involved: and ... by arguing that class interests lie at the base of much of the system through which housing is produced and distributed.

(ibid., p. 71)

Table 1.1: Four Approaches to Housing and Residential Structure

| Approach | Wider social theory | Areas of enquiry | Exemplar writers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ecological | human ecology | spatial patterns of residential structure | Burgess (1925) |

| 2. | Neo-classical | neo-classical economics | utility maximisation, consumer choice | Alonso (1964) |

| 3. | institutional managerialism locational conflict | Weberian sociology | gatekeepers, housing constraints power groupings, conflict | Pahl (1975) Form (1954) |

| 4. | Marxist | historical materialism | housing as a commodity; reproduction of labour force | Harvey (1973, part II) Castells (1977a) |

Source: Bassett and Short (1980).

Robson's fourfold classification finds support in the writings of Bassett and Short (Table 1.1) who distinguish between the ecological, the neo-classical, the institutional and the Marxist approaches. While

Figure 1.1: Established Areas of Housing Research Source: Bourne (1981).

Bourne's eight major research foci could be accommodated within these four major subdivisions, it would seem that the classification suffers from at least one important omission — the behavioural approach to consumer decision-making and residential mobility. This is recognised, in fact, by the authors but they see the behavioural approach as being extra to the scheme, developing out of the ecological and neo-classical approaches. Given the importance of the behavioural approach to the geography of housing (particularly in terms of the volume of research), it is felt that perhaps it warrants individual attention. With the addition of this behavioural category, therefore, it is Bassett and Short's scheme and terminology which will be followed here. As they have observed a 'distinction can be drawn between the earlier developed ecological and neo-classical approaches which focus on equilibrium conditions, housing choices and social harmony and the more recent resurgence of interest in institutional and Marxist approaches which focus on disequilibrium conditions, housing constraints and social conflict' (Robson, 1969, p. 3). Very crudely, this distinction can be equated with, as Bourne suggests, the distinction between those studies of residential differentials focusing upon demand-based explanations and those concerned predominantly with the methods of supply.

Demand-based Explanations

Essentially these studies have focused on the competition between households for land, a location within the city, and a dwelling. They incorporate three distinct lines of investigation — the neo-classical economic approach, the ecological approach and the behavioural approach.

The Neo-classical Economic Approach

Central to this approach is the development of a trade-off model similar to von Thunen's agricultural land-use model. Essentially the basic model has been modified to describe the pattern of land-use within the city. The basis of the approach is the theory that households and firms compete, within the constraints of their budgets, for space within the city, so as to maximise the satisfaction of the various competitors and the efficiency of the urban system. As with the von Thunen model, there are a number of qualifying assumptions which have to be made. First, it is assumed that man acts as a rational economic being and that perfect competition occurs between households and firms. Second, that the urban area is located on an isotropic surface in which transport is equally easy in all directions and transport costs are a direct function of distance. Third, that the Central Business District (CBD) is the most accessible location in the urban system and the only employment centre. Fourth, that the CBD is the most sought-after location, thus producing land prices in the centre which are higher than those in the periphery. In these circumstances, the firms and households compete for space and the residential decision is a 'trade off' between the cost of land and the cost of commuting. As Alonso (1960, p. 154) has observed households, in reaching their decision about where to live, are believed to balance 'the costs and bother of commuting against the advantages of cheaper land with increasing distance from the center of the city and the satisfaction of more space for living'. Under these conditions, the urban rich might be expected to live in large space-consuming properties at low densities in the urban periphery, while the urban poor, unable to pay the high costs of regular commuting, would live in cramped conditions in the inner city.

Although the model seems to fit the general pattern of housing within cities, over the years it has been refined and modified. For instance, the possibility of a multi-centre city has been considered by De Leeuw (1972), while Kain and Quigley (1972 and 1970) have attempted to take account of racial discrimination and variations in the quality of the r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Dedication

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. Housing

- 2. Employment and Unemployment

- 3. Crime and Delinquency

- 4. Ethnicity

- 5. Urban Government and Finance

- 6. Retailing

- 7. Transport

- 8. Health

- 9. Territorial Justice and Service Allocation

- 10. Pollution