![]() Part I: Competitive Intelligence

Part I: Competitive Intelligence![]()

Competitive Intelligence programmes for SMEs in France: evidence of changing attitudes

Jamie R. Smith, Sheila Wright and David Pickton

Department of Marketing, De Montfort University, Leicester, UK

This paper reports on an empirical study of the French Chambers of Commerce and Industry Competitive Intelligence (CI) programmes. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with the directors of 15 CI programmes from four regions of France. The research questions focused on definitional issues, CI programme content, Small and Medium-sized Enterprise (SME) CI practices and innovative methods used to change attitudes towards CI. The interview transcriptions were sorted, analysed and classified in NVivo software. The findings show that tangible results have been achieved despite resistance from small businesses in regard to their Competitive Intelligence practices. The paper also identifies the public and private sector entities which were named as sources of advice for small businesses for their Competitive Intelligence needs. The SMEs were also classified by the application of a CI attitude typology. The insights elicited can help future initiatives by public/private partnerships in both CI programme design and implementation.

Introduction

Over the last 10 years France has implemented regional programmes to increase the awareness of, and change attitudes towards, the Competitive Intelligence (CI) practices of enterprises. Dedijer (1994) identified France as the first country in the world to look closely at the relationships between government, intelligence and society. Uniquely in France, and in contrast to other European and North American countries, CI support is considered to be a state role (Carayon, 2003; Dou, 2004; Martre, 1994; Smith & Kossou, 2008) and to be implemented throughout French regions (Goriat, 2006; Moinet, 2008). The emphasis has primarily been on Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) with the Chambers of Commerce and Industry (CCI) playing a central role (Clerc, 2009). The overall objective of this study is to investigate the emerging French paradigm of CI as a public policy. Specifically, this paper addresses the roles and perspectives of the CI programme directors who interact with SMEs in the field. Table 1 summarises the research design.

Methodology

Gilmore, Carson, and Grant (2001) argued for a phenomenological approach to SME research with an emphasis on explanation and not prediction. A qualitative approach provides insight into the issue being explored (Creswell, 2007) illuminating the rich data found in local contexts (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004). CI itself has been defined as both art and science (Calof & Skinner, 1998) and, essentially, being qualitative in nature (McGonagle & Vella, 2002). Interviewing can be focused on meanings and frameworks as well as events and processes (Rubin & Rubin, 2005), all of which were captured in this evaluation research. The transcripts were uploaded into NVivo for coding and analysis. A case node was created for each CI director to form a constellation of sources around a person (Bazely, 2007). Coding the transcripts identified topics and brought together data where they occurred (Bazely, 2007). The construction of ranked tables identified emerging themes, frequencies and patterns (Neuman, 1997).

Table 1. Research design.

Sample frame | Chambers of Commerce and Industry in France |

Sampling method | Purposive/snowballing |

Sample size | 15 interviews |

Research approach | Qualitative, Exploratory, Descriptive |

Data collection methods | Semi-structured interviews and document analysis, face to face and telephone |

Data analysis | NVivo software to code, sort, classify and identify common themes |

Research questions | What is the content of your CI programme? |

| What types of firms are targeted in terms of size and sector? |

| Which organisations from both the private and public sectors do you collaborate with in your CI programmes? |

| Which organisations have the most credibility for advising on CI practices? |

| What terminology is used in the intelligence gathering process? |

| Who is responsible for CI in the SMEs? |

| What are the attitudes of the SME decision makers towards CI practices? |

| What actions do you take to change the SME decision makers’ attitudes? |

| How motivated are the SME managers to follow your advice? |

| How do SMEs evaluate the effectiveness of their CI practices? |

The sample frame

All but one CCI stipulated that their actions could be considered programmes. The sample frame included only CCI CI programmes that had been running for at least one year. The sampling methods used were purposive and snowballing. Purposive sampling enables the researcher to build a sample frame around a specific subject matter (Denscombe, 2007). Riley, Wood, Clark, Wilkie, and Szivas (2003) considered that sample units which provide information about themselves and about other units (snowball sampling) an effective social science method to identify suitable respondents. The programmes have evolved over time often solidifying related services and activities which started before the noted years. Rennes has two ongoing programmes; one interview was undertaken with each programme manager. Estimates were stated by the CI programme directors as to the numbers of SMEs which have participated in the CI programmes. The directors have considerable exposure to SMEs in terms of CI needs, SME attitudes towards CI and the effectiveness of the CCI activities. Most have interacted with over a hundred SMEs in some form of their programme implementation. There is an accumulated experience of 59 years for the interviewees in terms of directing CI programmes. Table 2 lists the participating CCI alphabetically.

Table 2. Participating CCI.

Chamber of Commerce | Year CI programme started | Estimated number of SMEs involved in programmes |

Bourgogne | 2000 | Over 100 in 2008 |

Chalons en Champagne | ‘activities’ since 1989 | Currently around 200 |

Chambery | 2007 | Around 12 companies |

Colmar | 2000 | Around 250 in 2008 |

Dordogne | 2008 | 50 |

Franche-Comté (regional) | 2006 | Around 150 |

Le Mans | 1998 | 80 a year face to face |

Lille | 2006 | Around 140 |

Paris | 2004 | Around 120 |

Rennes (regional) Dufour | 2005 | Around 100 |

Rennes (regional) Rodrigez | 2007 | Around 400 |

Rhone-Alpes (regional) | 2006 | Many hundreds |

Rouen 2007 | 2007 | 115 |

Tours | 2007 | Around 100 |

Versailles Val-d’Oise | 2006 | Between 300 and 400 |

Competitive Intelligence for small businesses

The case for SME research has been well established by management scholars (McGregor, 2005; Nkongolo-Bakenda, Anderson, Ito, & Garven, 2006; Ruzzier, Hisrich, & Antoncic, 2006). The investigation of CI in SMEs has not been as well documented as in larger companies (Burke & Jarratt, 2004; Tarraf & Molz, 2006). Early work by Groom & David (2001) suggested that SMEs were not very concerned with CI. A recent study in France by Oubrich (2007) suggested that SMEs were limited to conducting surveillance of markets and competition whereas large companies were integrating CI programmes into strategy development. Nevertheless, a few quite major studies have focused on SMEs. In Canada, Brouard (2006) looked at environmental scanning practices in SMEs. Salles (2006) examined the information needs of SMEs in France in order to conduct Competitive Intelligence. In Switzerland, a research-action approach showed the necessity of a strategic assessment to determine CI needs in SMEs (Bégin, Deschamps, & Madinier, 2008). A comparative study of Belgium and South Africa by Saayman et al. (2008) found that there were few differences between small and large companies in terms of intelligence practices. However, French CI research has highlighted the different practices between large and small companies (Bégin et al., 2008; Bulinge, 2001; Salles, 2006). In France, the situation is quite different in that Competitive Intelligence as a business discipline, especially for SMEs, is supported by government-sponsored programmes that are being implemented country wide (Moinet, 2008; Smith & Kossou, 2008).

The variables which influence CI activity are not well defined (Tarraf & Molz, 2006). There is a calling for more insightful ways to assess SMEs (Spickett-Jones & Eng, 2006). Qiu (2008) investigated how entrepreneurial attitude and normative beliefs influence managerial scanning for CI in large companies. The antecedent investigation of CI awareness and attitudes in SMEs however, remains a gap in the literature. This exploratory study can be considered an incremental step towards addressing the roles of attitudes and awareness in a CI programme context.

CCI Competitive Intelligence programmes

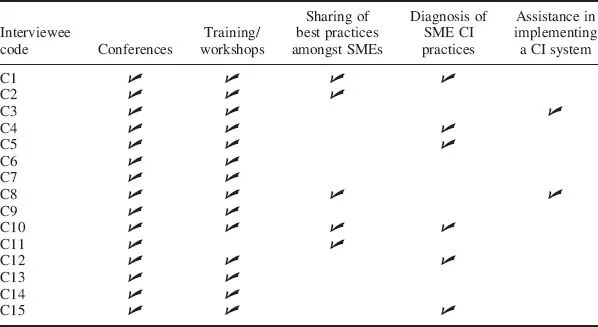

The CCI in France represent networking organisations that bridge the public and private sectors with an intimate knowledge of the entrepreneurial community (Clerc, 2009). The CI programmes are decentralised and do not take on a common format. However, as can be seen from Table 3, all the CCI disseminate CI concepts through conferences and virtually all engage in training and workshops. Many provide a diagnosis of the SME CI practices to determine which training and assistance is appropriate. Many also speak of accompanying the SME with their CI needs and this may go as far as setting up a CI system for them. Table 3 illustrates the CCI programme content.

Innovative approaches towards changing attitudes and practices

Approaches towards changing attitudes and behaviours surfaced during the interviews. As can be seen, the CCI were using both conventional and non-conventional means.

Theatre

One CCI used professional actors and a play to convey the importance of strategic information and other CI concepts to SMEs. The head of the programme was convinced it worked but more senior officials were reluctant to continue such an alternative method.

SME managers sharing experiences

Many CCI invite SME managers who have implemented CI programmes to forums to share their experiences with other SME managers. SME counterparts are considered by the CCI as the most credible source.

Table 3. Summary of CCI Competitive Intelligence programmes.

A CI animator split between four SMEs each in a different industry

An interesting approach was used by another CCI which created an original employment contract for a qualified CI specialist to work in four different SMEs. The consultant, who has a degree in Intelligence Economique, spent one day a week with each enterprise to set up tools and systems and train employees on CI techniques. As the four SMEs were from different...