![]()

1

Objects and materials

An introduction

Penny Harvey and Hannah Knox

Objects and materials — collaborative relations

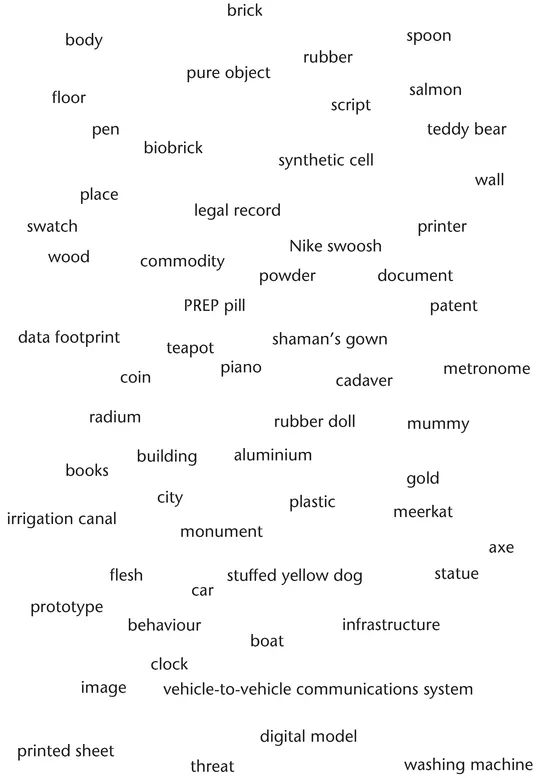

The array of objects and materials with which we open this Companion volume (see Figure 1.1) deliberately echoes the imaginary encyclopedic listing that Foucault draws from the work of Borges to show how things become intelligible through the relations that surround them. An encyclopedia, traditionally, does the job of revealing what a thing is by mustering and representing the relations deemed most relevant, and thus most useful to readers. Borges was working in the opposite direction. His fantastical encyclopedia revealed the unsettling effects of things grouped as if there were connections, when those connections are unfathomable to the reader. The effect was to undo the certainties, the habitual modes of classification, and to open things up to strange alternative possibilities. Foucault's (1970;.xxiii) interest in The Order of Things was to track back through Western intellectual history to reveal that the apparent certainties and stabilities of the modern social sciences were a mere 'wrinkle in our knowledge', a recent invention of the modern episteme.

Our introduction does not claim, nor does it aim, to provide an integrative overview or an account of a twenty-first-century episteme. Rather, it builds on the incidental nature of the objects and materials presented in this volume to uncover some of the preoccupations and philosophical questions regarding the heuristic promise of objects and materials in the contemporary social sciences and humanities. The chapters gathered here suggest that there is a general agreement across the humanities and social sciences that things are relational, that subject/object distinctions are produced through the work of differentiation, and that any specific material form or entity with edges, surfaces, or bounded integrity is not only provisional but also potentially transformative of other entities. At the same time, our array of objects holds no categorical promise. It is rather a set of empirical starting points for exploring just what the nature of such material or object relations might be, how differentiation occurs, and what the implications might be for seeing objects in terms of their transformative potential. All the objects and materials listed in Figure 1.1 are drawn from the work of our contributors. They are things that provoked reflections on the insistent presence of object forms in everyday life. And they open us to what objects and materials, separately and/or together, can draw attention to, or teach us about the worlds in which they appear.

Figure 1.1 Some of the objects and materials addressed in the Companion

This Companion thus sets out to accompany those who are interested in exploring how objects and materials actively participate in the worlds that we: research or otherwise engage as artists, practitioners and/or activists. Our primary objective is to interrogate the terms of our collaborations with objects and materials and to consider how these become integral to how we engage one another.

From the beginning, our approach to bringing this book into being has been as an exercise in interdisciplinary engagement. Our editorial collective grew out of a particular experiment in cross-disciplinary social science, which has, since 2006, gone under the name of CRESC: the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)-funded Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change. Within CRESC, different research groupings have emerged and each has worked in its own particular way. We have not systematically compared or drawn together our diverse disciplinary approaches to a common topic. Objects and materials were not our starting point. Rather, we came together as a group of people with a general interest in issues of politics: and cultural value. Our presence in CRESC suggested an openness to other ways of working, but at the same time, we each continued to work on these themes in our own way. The objects of our research focus were diverse. Periodically, we came together and listened to what others were absorbed by, we read each other's work, and took up suggestions of what to read. We began a reading group on Deleuze, we organized seminars on topics of common interest, and slowly the mutual influences grew until (at one of our annual residential meetings) we realized that a powerful common preoccupation was how to approach the presence of objects and materials at a time when, theoretically at least, the self-evidence of such things was overtly in question. We recognized that there were important differences in the way we were approaching the challenges posed by objects and materials. But we were reluctant to explain such differences in purely disciplinary terms. The differences seemed to have as much to do with the specificity of our empirical concerns as they did with the overlapping theoretical and analytical approaches that we brought to our work. We thus set about choosing, each from our own perspective, who we would like to introduce each other to: to read, to talk and listen to.The invited contributors to two key events in 2009, became the core of this collection.1

Our model of interdisciplinary engagement thus did not focus primarily on specific disciplinary histories and preoccupations. We were already in an intellectual space in which the objects and materials that engaged us were challenging any easy disciplinary containment. Working within the explicitly interdisciplinary space of CRESC, we were all reading across established canons and all looking for ideas and approaches from a variety of sources.

This is not to Say that our awareness of disciplinary tendencies was not important. Rather, we approached disciplines not as contained collectivities, but as particular, institutionalized gatherings of conceptual resources, as intellectual spaces where particular theories, philosophies and empirical findings shape research questions and the ways in which scholars go about answering them. We were interested in how disciplines change over time, diversifying, fragmenting but also consolidating around particular concerns and interests. It is for this reason that we have chosen not to rehearse here any specific history of disciplinary configuration. Instead, in this introduction We draw attention to the ways in which a collection such as this shows that although different disciplinary histories shape the ways in which scholars apprehend the empirical, they can never fully account for the routes that specific research trajectories will take. Patterns can be found, and they can be disrupted. Rather than taking our lead from a teleology of disciplinary thought, we start instead with the engagements with objects and materials as they appear in this volume.

Objects and materials — similarities and differences

There is no a priori resolution in this volume as to the nature of the distinction between objects and materials or the relationship between them. For some authors, the distinction between objects and materials is fundamental to their argument. Others treat the terms as more or less synonymous. Some authors work with a strong distinction between things and objects, others are more concerned to distinguish objects from artefacts. Some focus on processes of materialization and the material condition or materiality. Some allow materials to take pride of place. Still others are drawn to conceptual objects.

It is perhaps useful at this stage to note that it is the category of the 'object' that emerges as particularly contentious for our authors. The reader will find materials, things, artefacts and concepts deployed across the range of contributions (and they can be tracked through the index). But these terms are all far less controversial than the category of the 'object'. Materials and artefacts are generally understood in terms of a distinction between matter and a fabricated form. Materials are consistently used to refer to the constituent fabric of things, whereas artefacts denote specific constructions. Similarly, those who choose to talk about things rather than objects are connecting to a well-rehearsed and influential philosophical debate stemming initially from the rejection of the Kantian distinction between the thing as perceived by human beings, the passive object of human appropriation, and the thing as subject of its own movements and capacities, existing independently of human beings, unknowable and autonomous. There is a general agreement amongst our contributors that the value of the 'thing' concept in contemporary scholarship derives from an interest in attending to how things act back on the world, manifesting resistances, capacities, limits and potential, and thereby challenging the normative subject/object dichotomy. Concepts can also, in this sense, manifest thing-like qualities, which several authors explore. But although some authors are at times concerned about the objective qualities of concepts, the conceptual nature of abstract ideas is not particularly brought into question, although they materialize in unexpected ways in different contributions.

Where the trouble starts is with objects. And it is perhaps objects above all that reveal the need for a Companion guide to their diverse permutations. Objects are sites of intellectual dispute: there is no agreement on what objects are. Are they active or passive? Are they living or inanimate? Are they complete or in process? Are they material or immaterial? Do they shut you out or invite you in? In this volume, it seems that objects can be all these things. This confusion or profusion is exciting to think with and about. Indeed, the force of this debate appears to offer the potential to shed light not just on objects themselves but on broader questions about why objects have become so contentious in the current moment.

Objects and materials: why now?

Objects and materials do seem to have gained a particularly powerful purchase in the contemporary social sciences and humanities. A number of encyclopedias, readers and edited collections have been published in recent years that provide an introduction to the place of objects and materials in different disciplines, including anthropology, archaeology, sociology, and across the social sciences and humanities more generally (Graves-Brown 2000; Buchli 2002; Latour and Weibel 2005; Meskell 2005; Miller 2005; Tilley 2006; Henare et al. 2007; Candlin and Guins 2009; Cooper et al. 2009; Hicks and Beaudry 2010).

In the recent Object Reader (Candlin and Guins 2009),, Grosz explains the current interest in objects by suggesting that they seem to straddle a 'great divide' in philosophical approaches, allowing people to think in concrete terms about what is implied by the move from the Enlightenment traditions of Kant and Descartes to the thinking of those 'pragmatist philosophers who put the questions of action, practice, and movement at the center of ontology. What these disparate thinkers share in common is little else but an understanding of the thing as question, as provocation, incitement, or enigma' (Grosz 2009: 125). Grosz associates philosophers as diverse as Nietzsche, Peirce, James, Bergson, Rorty and Deleuze in this philosophical move, which suggests that they in turn were motivated by provocations from beyond philosophy, from a world where developments in science and technology were blatantly disturbing established paradigms. Sloterdijk has written of how the use of poison gas in World War I reconfigured military awareness of where danger might lurk, the previously abstract atmospheric conditions becoming a source of threat and potential harm, in turn preconfiguring new types of warfare in which the enemy is unseen, and potentially unidentifiable by traditional means (Sloterdijk 2009). Biotechnologies, to cite another example, opened new questions about life itself (Franklin 2007), and research in cellular technologies developed techniques that depended on 'making cells live differently in time, in order to harness their productive or reproductive capacities' (Landecker 2007: 212). Technological changes also provoked the law to assert new forms of ownership. Strathern (1995a), for example, discusses a ease brought to the Supreme Court of Justice in California in which a surrogate mother seeks to claim 'ownership' of the child to which she has given birth. Social studies of science and technology have repeatedly shown how material processes actively participate in the formation of philosophical and political constructs.

We cite several examples here to emphasize that we are not trying to produce a singular narrative that signals linear epochal change. We are simply wanting to point out how many contemporary objects destabilize object categories. We could add many more examples of...