![]()

The Great Barrier Reef

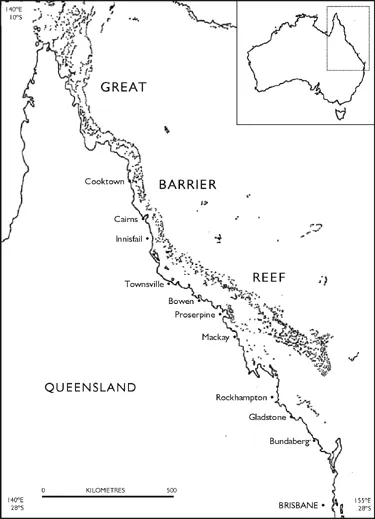

The Great Barrier Reef is the largest complex of coral reefs and associated habitats on Earth (Figure 1.1). The ecosystem extends for over 2,200 kilometres along the north-eastern coast of Australia, containing around 2,900 coral reefs and representing one of the most biologically diverse ecosystems known to exist (Hutchings et al., 2009; GBRMPA, 2013). Although there has been some debate about the age of the ecosystem and of its more ancient foundations, the modern Great Barrier Reef is a young structure in geological terms, having formed during the last 10,000 years of the Holocene epoch (Hopley, 2009; Hopley et al., 2007). Consequently, its modern reefs have always existed in relation to humans, supporting the subsistence economies of coastal Indigenous Australians and containing many places of cultural and spiritual significance. After European settlement commenced in Australia, the ecosystem played an important role in the colonial development of Queensland and its resources were subjected to more intensive exploitation (Bowen, 1994; Bowen and Bowen, 2002).

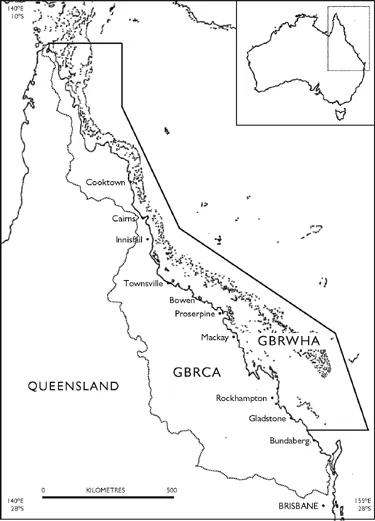

Although it lies in Australian waters, the significance of the Great Barrier Reef extends beyond Australia. The coral reefs and associated habitats of the region were first protected by the creation of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (GBRMP) in 1975. Subsequently, in 1981, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) acknowledged the outstanding universal value and global significance of the ecosystem by creating the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area (GBRWHA) (Lucas et al., 1997). The extent of the GBRWHA is approximately 348,000 km2, forming one of the largest and best known World Heritage Areas in the world (Figure 1.2). The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA), the lead agency responsible for the management and conservation of the GBRWHA, has faced considerable challenges in managing multiple human activities across the vast area of the ecosystem, and the Great Barrier Reef is regarded as one of the best managed coral reef ecosystems in the world (Wachenfeld et al., 1997; Lawrence et al., 2002).

Figure 1.1 The geographical extent of the Great Barrier Reef. Source: Author, adapted from Wachenfeld et al. (1997, p4)

The Great Barrier Reef is a large, complex, dynamic entity that is difficult to define precisely. It has been defined in various ways since Matthew Flinders first used the term ‘Great Barrier Reef’ in 1802 (Bowen and Bowen, 2002); Maxwell (1968) listed several of those definitions in his Atlas of the Great Barrier Reef. The term ‘Great Barrier Reef Province’ refers to the coral reefs of eastern Australia and Torres Strait, one of seven coral reef provinces in the south-western Pacific Ocean. The ‘Great Barrier Reef Region’ describes the large coral reef area that was initially designated for protection under Australian law; in 1975, that term was replaced by the GBRMP, which extends northwards as far as the latitude of Cape York but excludes the coral reefs of Torres Strait. The GBRWHA occupies approximately the same area as the GBRMP, although some variations exist in their coastal boundaries: the GBRWHA also includes the islands of the Great Barrier Reef, while the GBRMP consists of the marine environment alone (Lucas et al., 1997, pp36–7, 99). All of these terms are found in the scientific literature of the Great Barrier Reef, reflecting the problem of adequately describing the boundaries of this ecosystem. Yet most historical sources predate the definitions of the GBRMP and the GBRWHA, and many simply use the general term ‘Great Barrier Reef’. In this book, a broad definition of the Great Barrier Reef is used, one that encompasses the GBRWHA (including its islands) and the adjacent areas of Torres Strait, Hervey Bay and Moreton Bay, since some important historical changes occurred in each of those parts of the ecosystem.

Figure 1.2 The Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area (GBRWHA) and the Great Barrier Reef Catchment Area (GBRCA). Source: Author, adapted from Wachenfeld et al. (1997, p4); Furnas (2003, p2); GBRMPA (2009)

Conceptions of the Great Barrier Reef held by Indigenous Australians can differ significantly from those of non-Indigenous Australians. Many Indigenous Australians regard the Great Barrier Reef as part of traditional ‘sea country’; some also regard it as a sacred place whose importance is reflected in creation stories. Some marine animals found in the Great Barrier Reef, including dugongs and marine turtles, have formed a vital part of the social practices and cultural identities of some coastal Indigenous Australian communities. Given the significance of this ecosystem for biodiversity conservation, human use of the GBRWHA now raises important questions about self-determination, participation and co-management of coastal and marine resources by Indigenous Australians. Recently, scholars using postcolonial approaches (amongst others) have produced new interpretations of colonisation in Australia, developed better narratives of contact and resistance, and highlighted the need for more inclusive accounts of environmental history, particularly for settler societies. Their insights suggest that accounts of the environmental history of the Great Barrier Reef that exclude Indigenous Australian perspectives are, at best, partial and incomplete (Loos, 1982; Smyth, 1994; Jacobs, 1996; Reynolds, 2003).

However the Great Barrier Reef is defined, the ecosystem does not exist in isolation: it is closely interconnected with its adjacent environments. In particular, the GBRWHA is strongly influenced by its sources of freshwater, sediments and nutrients, especially the 35 drainage basins of eastern Queensland that form the Great Barrier Reef Catchment Area (GBRCA) (Figure 1.2). The GBRCA includes around 25 per cent of the land area of Queensland, and runoff from that area represents a major input to the GBRWHA. Therefore, the GBRWHA and the GBRCA form an interconnected unit: environmental changes in the GBRWHA may be closely related to both human activities and environmental changes in the GBRCA (Furnas, 2003). Significant land uses in the GBRCA include rangeland cattle grazing, forestry, sugar cane farming, cultivation of bananas and other tropical fruits, aquaculture and mining. In addition, rapid urban development has occurred in parts of coastal Queensland, and over one million people now live in the GBRCA. Economic development in coastal Queensland has also been significant, including the growth of the commercial fishing, shipping and tourism industries in the GBRWHA, with tourism now attracting around two million visitors per year. The cumulative effects of all of those activities – in both the GBRCA and the GBRWHA – have prompted concerns about the extent to which they have contributed to the large-scale degradation of the Great Barrier Reef, particularly its nearshore habitats.

The decline of the Great Barrier Reef

Concerns about the condition of the Great Barrier Reef (and of other coral reefs worldwide) increasingly focus on the global-scale threats to these ecosystems presented by climate change, especially the effects of coral bleaching, ocean acidification and sea-level rise. Such concerns are acute since it is now recognised that, under conditions expected to occur in the twenty-first century, global warming and ocean acidification will compromise the ability of corals to form robust carbonate skeletons, with the result that coral reef ecosystems are expected to become less diverse and to have reduced capacity to maintain carbonate reef structures (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007, p1737). In addition, those broad-scale changes are likely to interact synergistically with other impacts, exacerbating the effects of water pollution and disease, and thereby forcing coral reefs closer towards thresholds for functional collapse. Consequently, rapid climate change in conjunction with a range of other impacts is expected to lead to the widespread degradation and destruction of corals and coral reefs worldwide, with serious implications for tourism, reef-associated fisheries, coastal protection and human communities dependent upon reef resources (Hoegh-Guldberg, 1999; Lough, 1999; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007; Veron, 2009). Within that broader context, the resilience of coral reef ecosystems to the effects of climate change could be enhanced if other (regional and local) environmental stresses are minimised. From this perspective, it becomes important to characterise and understand the extent to which the Great Barrier Reef is – and has already been – affected by those other environmental stresses, including historical ones.

Although the current, global-scale threats to coral reef ecosystems – especially those due to climate change – are formidable ones, the deterioration of coral reefs may have commenced much earlier than those threats were first recognised. Many reports suggest that the condition of the Great Barrier Reef has declined since European settlement commenced in Queensland, as a result of direct exploitation and the development of adjacent coastal land. In particular, the terrestrial runoff of sediments, nutrients and other pollutants has probably caused a substantial deterioration of water quality in parts of the Great Barrier Reef, and those effects – together with the over-exploitation of reef resources – have significantly degraded some nearshore coral reefs and seagrass communities. The Queensland Environmental Protection Agency (QEPA, 1999, p5.4) reported that nutrient inputs to the Great Barrier Reef lagoon have increased substantially over the decadal timescale due to extensive land clearing, catchment development and coastal runoff, and that the relatively enclosed and shallow nature of the lagoon makes it relatively susceptible to the effects of eutrophication and deteriorating water quality. Williams (2001, pp3–4) argued that sediment discharges have increased by three or four times, nitrogen discharges have doubled and phosphorus quantities have increased by six to ten times since 1800; as a result, the impacts of terrestrial runoff of nutrients and sediments on coastal parts of the GBRWHA – due to both past and current land use practices – have become a significant cause for concern. The impacts of coastal runoff are most significant for nearshore reefs and seagrass beds within 20 kilometres of the coast, with the most severely impacted areas lying between Port Douglas and Hinchinbrook Island, and between Bowen and Mackay (Williams et al., 2002, p1).

The Commonwealth of Australia Productivity Commission (2003, pp xxviii, 37, 42) has acknowledged evidence of an increase in sediment and nutrients entering the Great Barrier Reef lagoon since European settlement, due to the runoff of sediments, nutrients and chemicals from agricultural and pastoral land, especially as a result of cattle grazing and crop production. This has led to the decline of corals, seagrass communities and fish populations. The Great Barrier Reef Protection Interdepartmental Committee Science Panel (2003, pp2, 9, 12–13) also found evidence of accelerated erosion and a large increase in the delivery of nutrients to the Great Barrier Reef over pre-1850 levels, with consequent disturbance of the ecological function of inshore coral reefs. The report stated that some areas of the Great Barrier Reef – those most affected by terrestrial runoff – now appear to be degraded and/or slow to recover from natural disturbances such as tropical cyclones. In addition to the effects of deteriorating water quality, the degradation of the Great Barrier Reef has also occurred due to the over-exploitation of reef organisms, leading to the depletion of resources at Langford, Heron, North West, Tryon and Lady Musgrave reefs, and near Dingo, Four Mile and Kurrimine Beaches (QEPA, 1999, p5.13). Particular damage has been caused by commercial and recreational shell collecting, commercial coral collecting, aquarium fish collecting and bêche-de-mer (trepang or sea cucumber) collecting (QEPA, 1999, p5.27).

Besides these scientific and official reports, many anecdotal reports of a decline in the Great Barrier Reef have been made, attributing the degradation of coral reefs and other parts of the ecosystem to a multitude of human impacts: shipping, dredging, coastal and marine pollution, sediment and nutrient runoff, habitat destruction, coastal development, fishing, tourism and the collection of marine specimens (Lucas et al., 1997, pp65–6). The degradation of the Great Barrier Reef is considered by some observers to have occurred – or to have accelerated – in living memory. The most severe degradation is thought to have affected the nearshore habitats in the most accessible parts of the ecosystem: in the Cairns, Townsville and Whitsunday regions, which have experienced intensive human use and substantial terrestrial runoff. Given the immense ecological, economic and social importance of the Great Barrier Reef, there has been considerable scientific and public interest in either confirming or refuting those anecdotal reports of decline in the ecosystem. Furthermore, establishing the extent to which the Great Barrier Reef has changed since European settlement is important to inform the effective management of the ecosystem. However, extensive, systematic, scientific monitoring of the Great Barrier Reef commenced only around 1970, and scarce scientific data exist for the earlier period. Consequently, anecdotal claims that the ecosystem has deteriorated – especially prior to 1970 – are difficult to assess using existing scientific baselines.

Aims and approaches

In an attempt to evaluate anecdotal reports of a decline in the condition of the Great Barrier Reef for the period before extensive scientific monitoring began – especially prior to 1970 – my research used an array of qualitative methods and sources to reconstruct the environmental history of the Great Barrier Reef. Specifically, my research documents the main changes that have occurred in the coral reefs, islands and marine wildlife of the ecosystem. Many qualitative sources, including documentary and oral history materials, provide indications of the condition of the Great Barrier Reef at specific locations and at various times in the past. Archival and oral history sources, in particular, have been little used to investigate changes in the coral reefs, islands and marine wildlife of the ecosystem. A wide range of documentary materials was collected from Australian and UK archives, libraries, museums and historical societies. Those sources were used to complement and cross-reference a variety of oral history materials (both pre-existing and original): in particular, semi-structured, qualitative interviewing was used to collect new oral history evidence from informants who had observed human activities and environmental changes in the Great Barrier Reef. In addition to presenting an environmental history narrative of some of the main changes in the Great Barrier Reef since European settlement, I also evaluated the potential for qualitative methods to inform research into coastal and marine environmental history.

Coastal and marine environmental histories are not abundant in the scholarly literature, and environmental histories of coral reef ecosystems are very rare. Within the academic sub-discipline of environmental history, Australian studies comprise only a small subset, and most of those focus on the terrestrial themes of forests, soils and agriculture. There is a strong geographical bias in the literature of Australian environmental history in favour of environments in south-eastern Australia, whilst other areas have been comparatively neglected. Environmental histories of the Great Barrier Reef are very scarce: two notable works have been produced, by Bowen (1994) and by Bowen and Bowen (2002), but those focus principally on the history of exploration, environmental policy and management in relation to the Great Barrier Reef rather than on specific changes in the coral reefs and associated habitats of the ecosystem per se. Moreover, whilst Bowen and Bowen (2002) made extensive use of documentary materials, there is scope for a new account based on the analysis of archival sources – including some recently-available records of the former Queensland Department of Native Affairs (QDNA) – and on original oral history evidence.

Conceptual, theoretical and philosophical questions about environmental history have generated considerable debate among practitioners, and the field is characterised by a broad diversity of methods and approaches. One particularly inclusive approach is Cronon’s (1992) narrative approach, which considers the task of environmental history to be, above all, the production of narratives, and which acknowledges the central role of a narrator in telling a convincing story about environmental change. Such an approach acknowledges that perceptions of environmental change reflect the diverse views of individuals in specific communities; it is therefore well suited to the collection and interpretation of qualitative materials, including the archival records of government departments and the (equally) value-laden, interpretive nature of oral history sources. In its methodology, my research was informed by the approach of Denzin and Lincoln (2000, p3), who defined qualitative research simply as ‘a situated activity that locates the observer in the world’. Those authors argued that qualitative research is a distinct field of academic inquiry that is concerned with the interpretation of empirical materials in order to produce representations, such as recordings and texts; consequently, the outcome of qualitative research is itself an interpretation of reality. Like Cronon’s (1992) narrative approach to environmental history, Denzin and Lincoln’s (2000) approach to qualitative research emphasises the pivotal position of the researcher, whose values and attitudes fundamentally influence the research process. Therefore, those two approaches are complementary: each uses postmodern critical theory, examines the role of the narrator/researcher and emphasises the social and political contexts of representation.

Some environmental historians have emphasised the importance of reconstructing past environments in order to derive baselines that can be used to assess environmental change (Dovers, 1994; Gammage, 1994). Such reconstructions of the baseline condition of the Great Barrier Reef at the time of European settlement – if those were possible to produce – could reveal subsequent changes in the coral reefs and associated habitats of the ecosystem. Some researchers have attempted to establish this type of baseline using historical sources: Wache...