- 270 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Made in Japan serves as a comprehensive and rigorous introduction to the history, sociology, and musicology of contemporary Japanese popular music. Each essay, written by a leading scholar of Japanese music, covers the major figures, styles, and social contexts of pop music in Japan and provides adequate context so readers understand why the figure or genre under discussion is of lasting significance. The book first presents a general description of the history and background of popular music, followed by essays organized into thematic sections: Putting Japanese Popular Music in Perspective; Rockin' Japan; and Japanese Popular Music and Visual Arts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Made in Japan by Toru Mitsui in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mezzi di comunicazione e arti performative & Etnomusicologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Putting Japanese Popular Music in Perspective

Part I groups together five chapters that are historically oriented with different topics, hence putting Japanese popular music in perspective.

The first chapter, “The Takarazuka Revue: Its Star System and Fans’ Support,” investigates the Takarazuka Revue in relation to its unique star system and the role of fan clubs. Serious and substantial research on this famous revue and its company of all-female performers founded in the 1910s in the hot-spring resort of Takarazuka was carried out mostly by overseas female scholars, and its analysis was from the perspective of gender as well as of Japanese modernism. Naomi Miyamoto, who has familiarized herself with the fans by belonging to various fan clubs, maintains that the revue since the 1980s cannot properly be examined from those points of view.

The next chapter, “‘Infinite Power of Song’: Uniting Japan at the 60th Annual Kōhaku Song Contest,” gives an overall picture of the most important popular-music TV program that represents the mainstream popular music in Japan, and focuses on the show in 2009, for which the theme chosen was “The Infinite Power of Song.” The show, broadcast annually on New Year’s Eve since the early 1950s, is examined as a reminder that the audience is “all part of a wider sphere of belonging: the Japanese nation.” Shelley D. Brunt’s chapter is included here because of its good quality as well as the lack of academic studies on Kōhaku by domestic authors.

It is followed by an interesting portrayal of “The Culture of Popular Music in Occupied Japan.” This third chapter demonstrates that the genesis of postwar Japanese popular music can be found in the performances of jazz and current American hit songs by Japanese musicians on U.S. military bases in the Occupation (1945–52), before giving an overview of how those music practices shaped the culture of Japanese popular music After the Occupation. Mamoru Tōya’s research includes an employment survey in the military clubs in Yokohama bases as well as interviews with those who were employed.

Enka, which appeared as a new genre more than a dozen years After the Occupation and was generally recognized as authentically Japanese, is discussed in the fourth chapter, “The Birth of Enka,” as an example of the “invention of tradition.” “Gloomy and sentimental” enka is considered to have been “constructed as a countercultural discursive practice in the intellectual climate of the 1960s” against the penchant of the political Leftand progressives for “cheerful and wholesome” popular songs. It is generationally interesting that the authuor, Yūsuke Wajima, elucidates what the Editor of the present volume experienced in his twenties.

Then, follows the last chapter in Part I, “Songs in Triple Time are Still Sung in Duple Time,” by the Editor, Tōru Mitsui, with a song that became very popular in the mid-1920s as one of the materials for discussion—a song classified as enka long before the birth of a new enka. It is argued in this chapter that songs in triple time had also been sung in duple time by the Japanese since the beginning of the twentieth century, when they began to be composed domestically and that even now the practice is common among many people. In terms of metrical structure, two bars in triple time are spontaneously converted to three bars in duple time. The author is too old to be ranked with other contributors in the present volume, but was obliged to rush in at the last moment to fill up an aborted contribution.

1

The Takarazuka Revue

Its Star System and Fans’ Support

The Takarazuka Revue since the 1980s

Revue was born in France in the early nineteenth century, and it developed in various countries, most prominently in the United States and England. The genre usually features a theme and contains a series of scenes, including episodes of dance, songs, or sketches (Deane 2001: 242–4; Berlin 1991: 35); fundamentally, it is a type of pasticcio. Although its themes were originally rooted in satire or contemporary affairs, in later development this was abandoned in favor of fragmental scenes of spectacles, magnificent stages and costumes, and the latest stage technology, which are now the main focal points of the genre. Revue was at its zenith in Western countries during the 1920s; After that, its preferred position was taken over by new entertainment media such as film, radio, and records (Klein 1985: 185); today it no longer occupies a core place in show business.1

Although Japanese society in the 1920s was also influenced by this mode of entertainment and several revue companies were established, they experienced the same fate as Western revues. However, one Japanese company continues to perform revues regularly: the Takarazuka Revue Company.

The Takarazuka Revue, which consists of only female performers, is generally known for its musicals rather than its revues. Except for a few productions around 1930, its revue productions have not experienced any great success. The company has since established a regular performance style made up of both musical play and revue; the former is the main performance, and the latter, supplementary. Revue should not be neglected, however, though it plays a subordinate role, for the Takarazuka Revue continually creates and offers new revue productions. Not only is it unique in Japan; its like is rarely found anywhere else in the world. Today, revues are usually enjoyed at nightclubs or in casinos as incidental entertainment, while in the Takarazuka Revue, which has two of its own theaters, revues still survive as a form of show business.

How is it that the Takarazuka Revue Company can continue to produce revues in an environment that is, globally speaking, indifferent to the form? The present chapter aims to explore the Takarazuka Revue in relation to its star system and fans’ support.

As seen in Robertson’s study (1998), previous research on the Takarazuka Revue mostly consists of analysis from a gender perspective, because its performances are carried out only by women and most of its fans are also female (Berlin 1991: 39). These gender-based analyses of Japanese modernization2 were a suitable angle of study until the 1970s. However, the situation in and After the 1980s should be distinguished from that which had gone before. This chapter discusses the Takarazuka Revue and its reception After the 1980s. There are two reasons for focusing on this period: first, the company introduced a star system; second, fan activities were organized in accordance with this system. In the 1990s, when both the star system and fan organizations had already been established, the Takarazuka Revue experienced its golden age. Since the 1980s, the Takarazuka Revue can no longer be fully investigated from the perspectives of gender and Japanese modernization.3 Japanese society entered a new phase After experiencing a period of economic growth, the “bubble” economy, and the following period of recession. The Takarazuka Revue business was influenced by these economic situations, although it has managed to survive. Today, the Takarazuka theater is not a place where individual female fans directly show their adoration for male-role performers; rather, fan clubs act as intermediary organizations between the stars on stage and the audience. Consequently, the gender issue also needs examining from a different perspective, one that takes into account this fan system.

The definition of the “Takarazuka fans” in this discussion means those who belong to fan clubs that have been formed expressly to follow each performer, since many fans were organized into a coherent club system After the 1980s. There has not been any previous research on Takarazuka that focuses on fan clubs.4 As Stickland insists, there are a large number of fans not affiliated to any fan clubs (Stickland 2008: 138–9). However, it should be noted that general observations relating to the characteristics of “Takarazuka fans” are mostly those of fan clubs’ activities—for example, waiting in line in front of the stage door or wearing uniforms. Furthermore, such organizational activities can also influence individual fans who do not belong to the clubs. Fan clubs that acquire many tickets, occupy many seats, and are closest to the performers, cooperate with Takarazuka’s company administration, and are therefore more powerful in various ways than the individual fans who are scattered around the theater. This chapter examines the Takarazuka Revue based on this assumption, and draws from my own experience of belonging to various fan clubs over a period of around twenty years (Miyamoto 2011).

The Introduction of Revue and the Birth of the Male-role Player (otokoyaku)

It is not the intention of this chapter to describe the Takarazuka Revue Company’s history; detailed explanations already exist, such as those in the works of Robertson (1998) and Stickland (2008). Here, only the essential events of its history are outlined.

The Takarazuka Revue Company started as “Takarazuka Girls’ Opera” with the aim of providing entertainment in a hot spring resort, and was established by the Hankyū Dentetsu, a railway company. The opera achieved popularity because its productions were made up only of girls. It did not include any element of sexual expression or eroticism; rather, it offered “healthy” entertainment for families, which was the aim of the founder, Ichizō Kobayashi. However, as the Takarazuka performance became more popular, it encountered a limitation because it always offered female performers. When the Takarazuka Company began to encounter difficulties, the revue genre was introduced from France and it revitalized the company. Tatsuya Kishida and Tetsuzō Shirai, who had traveled in Western countries to solve the company’s crisis, brought this genre into the Takarazuka repertoire. The first revue for the Takarazuka Revue, and for Japan, was Mon Paris in 1927.

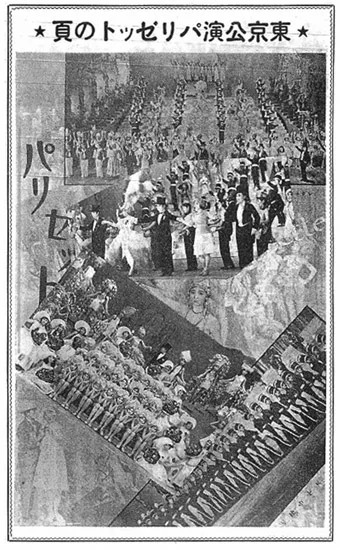

The brand-new colorful stage, illumination technology, stage sets, and the Western songs and dances in revues attracted the Japanese in those early days and revues caused a sensation in Japanese society. In addition, another revue, Parisette, which Shirai produced in 1930, achieved great success (see Figure 1.1). The theme song of this revue, “Sumire-no Hana Saku-koro’ (When

Figure 1.1 A collage of photos taken at the performance of Parisette in Tokyo. From Kageki, a monthly published by Takrazuka ShMjo Kageki-dan, December 1930, p. 41.

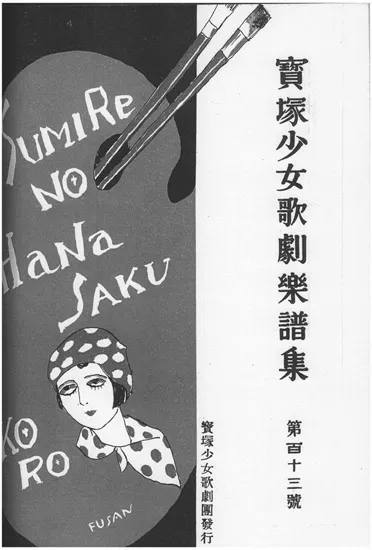

Violets Come into Blossom), turned out to be enormously popular not only among the Takarazuka audience but also throughout Japan (see Figure 1.2). It was originally a German popular song, “Wenn der weisse Flieder wieder blüht,” composed by Franz Dölle in 1928, which was translated the following year into French with the title “Quand refleuriront les lilas blancs.” Impressed by the song performed in a Parisian revue, Shirai translated it into Japanese. “Sumire-no Hana Sakukoro” is still sung in the Takarazuka performances even today.

Figure 1.2 The cover of Takarazuka ShMjo Kageki Gakufu-shū (Takarazuka Girls’ Opera Songbooks), No. 103, featuring the title of “Sumire-no Hana Saku-koro” in Roman letters (published in 1930 by Takrazuka ShMjo Kageki-dan). The use of Roman letters remains stylish among the general public.

In the 1920s, the all-female revue companies Osaka Shōchiku Opera Company and Shōchiku Opera Company were also founded. The founding of these and the Takarazuka Revue reflected the global popularity of revue, and this was especially important to Japan, which was keen to modernize. More importantly for the Takarazuka Revue, theatrical gender roles became more clearly defined as a result of the revue performances.

Before the introduction of revue, female performers had played male characters in accordance with the stories of plays or musicals. However, for the first time, productions required general male-role players who were independent of the characters in stories. In revues, performers had to play male roles or female roles which were not characters in a particular dramatic narrative. Conse...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Series Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction Embracing the West and Creating a Blend

- Putting Japanese Popular Music in Perspective

- Rockin' Japan

- Japanese Popular Music and Visual Arts

- Coda: Japanese Music Reception

- Afterword

- A Selected Bibliography on Japanese Popular Music

- Index