![]()

Part One

Chance in Physical Reality

I.

Notions of Random Mixture and Irreversibility

It is quite probable that the concept of chance starts from the idea of an increasing and irreversible combination of phenomena. Cournot’s famous interpretation conceived of physical chance as the interaction of independent causal series. But this complex notion, which needed an understanding of both interaction and independence, could hardly be grasped by the uninformed mind except in those cases where an intentionalist interpretation was eliminated because of the large number of elements involved. When a child is struck by a door which a gust of wind has closed, the child will find it difficult to believe that neither the wind nor the door had the intent of hurting him; he will certainly see the interaction of causes which brought him near the door, and also what caused the door to move, but he will not admit their independence. It is this fact which will not let him see the event as fortuitous. On the other hand, he does not recognize that chance characterizes daily happenings (social, meteorological, etc.) because he fails to notice the interactions of phenomena (e.g., the relationship between night frosts and the flowering of a fruit tree). In brief, the alternatives which have kept the child (as well as the primitive mind) from constructing the idea of chance are his recognition of either an interaction of causes with no recognition of their independence, or their independence without realizing their interaction. On the other hand, a combination of a sufficiently large number of elements seems to give a situation favorable to the intuition of causal series which both interact and are independent since the sequence of events is easily established with no need for imagining that there is anything intentional in the details.

The problem then is to determine if the child, in the presence of an obvious mixture of material objects, will perceive it as an increasing and irreversible mixture of the objects; or if, in spite of the obvious disorder, he will imagine the different objects as still being linked by invisible connections. In other words, is the intuition of the random mixture primary or does the concept of chance have a history? And if so, what is its history? This is what we mean to establish by experiment.

1. Technique of the experiment and general results.

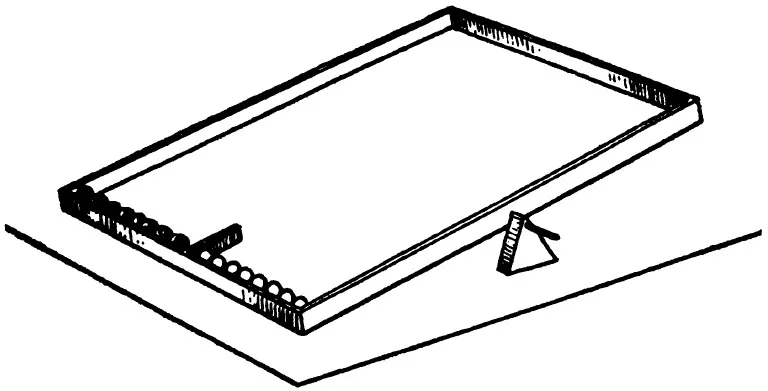

The child is given a rectangular box which rests on a transversal pivot, allowing it to seesaw. In a state of rest, the box is inclined to one or the other of its shorter sides, and along this width are arranged eight red balls and eight white balls, each group separated by a divider (Figure 1). At each seesaw movement, the balls will roll to the opposite side and then will return to the original side when the box is tipped back, but in a series of possible permutations. The successive movements of the box ought not to be done too brusquely; in this way the mixture will proceed in gradual steps. For example, in the beginning, two or three of the red balls will be mixed with the white ones, and vice versa, and then the mixture will, little by little, be greater.

Before the box is first tipped (but telling the child or showing him how it moves while holding the balls in place), the child is asked a question: What will be the arrangement of the balls when they return to their starting places? Will the red ones stay on one side and the white ones on the other? Or will they get mixed up, and in approximately what proportion? We then proceed to tip the box and have the child note that two or three of the balls are in different positions. Then he is asked to predict the result of a second move which we then make, and so on. After some tries, he is asked to predict the result of a large number of moves of the box, and we note especially if he expects a progressive random mixture or a general crisscrossing of the red balls to the side of the white ones, and vice versa, and finally a return to their original order (that is, a final reordering).

Making a drawing of the arrangement of the balls can help in the questioning: He can draw his prediction of the first tipping of the box, and then after the first trial, make predictions by drawing the outcomes of successive trials. We will ask him in particular to draw an arrangement of the balls which he thinks is the best possible mixture. There is not always a connection between the drawing of the balls in their mixed positions and the trajectories of the balls which he is asked to draw. But an examination of this lack of agreement is quite useful for an interpretation of the thought process of the subject.

One notices that the different questions lead quite naturally to examining also the manner in which the subject conceives of the operation of permutations. We will return to this point in Chapter VIII, indicating there the technique to be used for the study of the development of these operations. We will note here only that it is a help to question the same children simultaneously by means of the tipping box of balls and also by means of the experiment with the permutations of counters (Chapter VIII). The correlation between the evolution of ideas concerning mixture and the development of the operations of permutation is an instructive factor in the interpretation of responses.

To remain for the moment with the mixture of the balls, the reactions observed at the time of the preceding questions permit us to distinguish three different stages. During the first stage (up to seven years), the mixture is conceived of as a total displacement of the elements, but without any intuition of a permutation of the individual positions nor any anticipation of an interaction in the trajectories. This total displacement certainly yields a state of disorder, but for the child it is not final and he often predicts that the balls will ultimately return to their original order. There is not, in the strictest sense, either a real mixture or chance. In the course of the second stage (from seven to eleven years as median), there is a progressive individualization of the positions, then of the trajectories, with the gradual construction of an intuitive scheme of permutations, but without a complete generalization. In the course of the third stage (over eleven to twelve years), the mixture is conceived of as a system of permutations due to the fortuitous collisions in the trajectories.

2. The first stage (four to seven years): Failure to understand the random nature of the mixture.

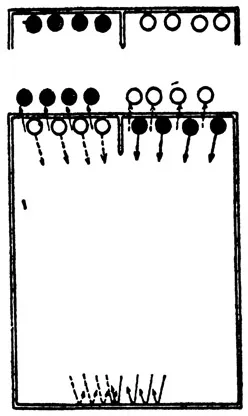

The reactions of the first stage are characterized by a very significant conflict between the facts noticed by the child which force him to see a progressive disorder and the interpretations which he searches for and which remain foreign to the idea of random mixture. In other words, the subject is obliged to accept the evidence of the changes of position due to the mixing, but he refuses to see in this a fortuitous mixing and decides to look for uniformities contrary to chance. Thus, in spite of the first permutations which the subject foresees, he predicts the return of the balls to their original places or perhaps a regular change of position, but not haphazard arrangements. For example, each ball is supposed to follow only a single trajectory—in particular, the red balls are to replace the white ones, and vice versa (Figure 2). A large number of movements of the box will not increase the mixture, and frequently the subject even expects a return of the balls to their original places. As for the drawing of the trajectories, rather than giving the child the idea of permutations, on the contrary, it leads him to the idea that the ball will come back to its starting place even when the fact of mixing has been previously established.

Here are a few examples:

ELI (4; 4) begins by predicting that the balls will return to their places. “They will go there (a few centimeters from the point of rest).” And then: ‘They will all come back in place (perfectly arranged).” “Watch (the box is tipped and one white ball passes into the area of the red ones).” “See, it’s just as I said.” “Look again.” “One white ball went over there (to the red side), but all the red ones are there.” “And when I tip it again?” “The white ones will be here and the red ones there (complete crossing of all the balls).” “Take a look (another tipping and the mixture is greater).” “Ah, it’s all mixed now.” “And if I keep it up, will it be more or less mixed?” “No. Don’t do that (he puts the balls back in place as if the mixture had bothered him).” “Now draw them for me as mixed up as they can be (he makes a drawing showing six white balls on one side, and on the other side three white ones together and three red ones).”

FER (5; 3): “What if I tip the box?” “The balls will get all mixed up” “How?” “The white will go there and the red there (crossing of reds to one side and white to the other).” (He makes a drawing of six reds on the right and six white ones on the left.) “Where will that ball go if I tip the box?” “There (return to the same place).” “You had said that the white balls would go there and the red ones here?” “No, they will return to their places.” “Watch (the experiment).” “They got mixed up. They crossed over and the red ones came over here and the white ones went there (in fact, this only happened to two).” “And if we tip again?” “They’re going to get mixed up again. They’ll go there and then there.” “Draw me a picture of how it will happen (he draws again six white balls on the left and six red ones on the right).” “Where will that white ball go?” (He draws a line which takes it to the other side on the right.) “And this red one?” “It will go over and stop there (inverse movement).” Fer continues the same drawing for the balls as follows: All the red ones move now to the left and all the white ones to the right making a complete crossover. At first there is a symmetry in the courses drawn, but after drawing some awkward lines, Fer puts the balls wherever he finds a free space which gives the appearance of there having been collisions in the trajectories, but the drawing is not done with the intention of showing any collisions.

VEI (5; 6): “If I tip the box, how will the balls then be lined up?” “Just as they are now.” “Take a look (we tip the box: one red passes into the white section and one white into the red.” “They can’t come back the same.” “And if we continue?” “Then they will get even more mixed up.” “Why?” “Because two of them will roll to the other side” “And if I tip the box again?” “Another one will move (three red balls in with the whites and vice versa).” “And the next move?” “Again one will move. They will get mixed even more (crossing over) and afterward they will start to come back to where they started (by crossing in the opposite direction: the red ones will come back to their original position and the white ones too.)” “Watch (and we tip it again but this time there is only one red mixed with the whites and one white with the red ones).” “And if we continue?” “It will stay as it is (Vei holds with what he sees).” “And if we continue doing this all afternoon, what will it be like?” “It will all come back in place as it should” Again we ask him for a drawing showing the maximum mixture: All the red balls are shown on the side which originally held the white ones and vice versa.

MON (5; 8) foresees correctly, from the start, that the balls will not “remain in their places” nor will they be completely mixed. “They will roll.” “Watch (the experiment: one red ball rolls in with the white ones and vice versa).” “They didn’t stay in their places; a red one is here and a white there “And if we continue, can we know what will happen?” “No, no one can be sure because we aren’t balls “Correct. But if we do it again, which will most certainly go to the other side, this red one which is in with the whites, or one of these whites?” (Hesitation.) “The red one, because it has to be in its place” “Do you want to try it?” (He does the experiment and one more red goes over with the whites.) “Now what do you say?” “They know where to roll because they roll all by themselves”

SCHU (5; 6): The same initial carefulness and the same tendency to believe that the balls will come back into place. He draws a series of trajectories going and returning: “Why? Will each one return to its place?” “They know where to go because they’re the ones who have to do it”

CAR (5; 8): “They’re going to roll to the other side and then come back” “How?” “The reds on one side and all the whites on the other side” “There is no chance that they will get mixed up?” “Maybe not completely; two reds will go here and two whites there” (We do the experiment: the mixture starts.) “And if we continue?” “They’ll come back as they were before” “Watch (another move of the box: the mixture increases).” “And if we continue?” “Still more mixed” “And finally?” “All the red ones will be here and the white ones there (complete reversal).” “And then?” “Like that (a return to the original position).” “It will come back to the way it was”

TAI (5; 8) after having seen the mix start: “It will get mixed up less as we continue”

YVE (6; 2): “The red ones will come back there and the white ones there (as they had been).” “Will they come back as they were, or will they get mixed?” “Come back” “Watch (the experiment: one of each goes to the other side).” “Ah! no, one here and one there” “And if we continue, will they mix...