![]()

Part I

Literature and the representation of reality: a new approach to fantasy and mimesis

Introduction

Like M. Jourdain, who discovered that he had been speaking prose all his life, readers of this book may find they have been reading fantasy, teaching it, and writing about it without ever having brought their critical consciousness to bear on the fantastic elements. To many academics, after all, “fantasy” is a subliterature in lurid covers sold in drugstores; or it is a morbid manifestation of the romantic spirit found in the works of Hoffmann, Poe, and less reputable gothic writers. Or fantasy means Tolkien and his ilk – nineteenth- and twentieth-century authors whose œuvres are not part of traditional literature courses. But fantasy encompasses far more than these phenomena. It informs the spirit of all but a small part of western literature. We are curiously blind to its presence because our traditional approaches to literature are based on mimetic assumptions. Philosophy and Christianity have denigrated the non-real on various grounds, with the result that we have never developed an analytic vocabulary for exploring and understanding fantasy. Even now, we can form ideas about it only with difficulty, and must struggle to wrest our insights from the inchoate imprecision of wordlessness.

Part I of Fantasy and Mimesis will briefly examine what has been done to remedy our lack of critical understanding. Chapter one analyzes definitions of fantasy that have emerged in the last two decades and shows how they relate to one another. Chapter two sketches the history of fantasy as a literary phenomenon. When has it been most common? Why did it fall into disrepute? Why is it reappearing so frequently in contemporary writing? Only when we have become sensitized to the prevalence of fantasy can we go on in Part II to study literary responses to reality, both fantastic and mimetic. These responses are complexly varied. Imitation and imaginative transformation, metaphor and allegory, whimsy and myth interact in such elaborate patterns that creating divisions for critical purposes may seem as impracticable as separating the dancer from the dance.

But one can enjoy watching the dance the better for knowing the steps, can better appreciate the grace with which figures are executed for understanding how difficult they are. Recognizing and responding to the fantasy element in literature requires such knowledge. Part I will attempt to supply the foundation on which such knowledge can be built.

![]()

1

Critical approaches to fantasy

The doctrine of mimesis was the foundation of the Greek aesthetic; it is probably the best foundation for any aesthetic. (John Crowe Ransom, “The Mimetic Principle”, The World’s Body, 1938)

The disenfranchisement of fantasy

Today, Ransom’s naive statement leaves much to be desired as a critical dictum, given our belated recognition that texts cannot transcribe reality, and indeed mostly refer to other linguistic conventions. Barthes’ S/Z exposes some of the insufficiencies of mimetic assumptions even when those assumptions are applied to literature we think of as realistic. Robbe-Grillet insists that although description of things “once claimed to reproduce a pre-existing reality…. Now it seems to destroy them, as if its intention to discuss them aimed only at blurring their contours, at making them incomprehensible.”1 The extreme position posits that there is no discussable relationship between literature and reality but, in practical terms, most words in any normal narrative refer to the commonalities of human experience, and few readers can be persuaded to relinquish all expectation of meaning in a text. They will put the book down rather than try to respond to words which are being offered only as aesthetic squiggles or melodic sounds or even as infinite interplay of signifiers. Literature bears an inescapable resemblance to reality, and the more the work tells a story, the more necessary the presence of the real. Nonetheless, it is an astonishing tribute to the eloquence and rigor of Plato and Aristotle as originators of western critical theory that most subsequent critics have assumed mimetic representation to be the essential relationship between text and the real world.

The tribute, though deserved, is not altogether a happy one. We might rather say that Plato and Aristotle between them tore a large and ragged hole in western consciousness. Ever since their day, our critical perceptions have been marred by this blind spot, and our views of literature curiously distorted. To both philosophers, literature was mimetic, and they analyzed only its mimetic components. Moreover, insofar as their assumptions allowed them to recognize fantasy at all, they distrusted and disparaged it. Aristotle judged literature according to how probable its events and characters were; realistic plays he held to be better than those using fantastic gimmicks like the deus ex machina. Although Plato frequently used fantastic myths to clarify his more mystical arguments, he too tended to insist on the mimetic nature of literature. He banned it from the Republic because this essential feature made it a shadow of a shadow and because the object of the mimesis was too often unworthy emotion. In the Phaedrus, moreover, he seems unenthusiastic about the fantastic elements in traditional myths. He certainly derides attempts to rescue them through rationalization, and does not seem well disposed to the mythic monsters taken at face value.

In truth, the passage from the Phaedrus quoted in the preface has cast a long shadow on literary theory. Plato may have approved fantasy in some guises, since he entrusted important ideas to its images, but his negative views are the ones to have influenced later generations. Its mythic avatars, the winged horse and the chimera, leave their trail throughout later expressions of disdain for fantasy. Tasso, for instance, mentions flying horses, along with enchanted rings and ships turned into nymphs, as permissible for the ancients, but a breach of decorum for his contemporaries. Hobbes concedes that impenetrable armor, enchanted castles, and flying horses were apparently not as displeasing to the ancients as they should be to men of good sense in his own day. George Granville’s “Essay on Unnatural Flights in Poetry” (1701) admits Parnassus, Pegasus, the muses, and the chimera to be acceptable poetic fictions, but condemns dwarves and giants as extravagant. David Hume disparages literary fantasy as a threat to sanity: romances, he claims, deal with nothing but “winged horses, fiery dragons, and monstrous giants”, and he fears that “every chimera of the brain is as vivid and intense as any of those inferences, which we formerly dignify’d with the name of conclusions concerning matters of fact, and sometimes as the present impressions of the senses”.2

Christianity unconcernedly perpetuated mimetic assumptions, and at the same time it further muddled critical perceptions of fantasy. The seductive attractions of classical literature included fantastic creatures and deities of an alien faith, so early Fathers of the Church developed a rhetoric of rejection that debarred these fantasies and, by implication, did the same to other fantasies as well. To many earnest Christians, literary fantasy has seemed a species of lie. The enemies of poetry addressed by Boccaccio and Sir Philip Sidney evidently numbered such literalists in their ranks; the Plymouth Brethren parents of Edmund Gosse considered all fiction whatever to be reprehensible lies. We see the secularization of this literalmindedness, and its extension as a mingling of Protestant and scientific seriousness, in Hard Times. Dickens is sensitive to the irreducible issue of fact versus non-fact, and he choreographs an elaborate battle between the two. An instructor expounds the literalist position to the hapless pupils:

You are to be in all things regulated and governed … by fact. We hope to have before long, a board of fact, composed of commissioners of fact, who will force the people to be a people of fact, and of nothing but fact. You must discard the word Fancy altogether. You have nothing to do with it. You are not to have, in any object of use or ornament, what would be a contradiction in fact. You don’t walk upon flowers in fact; you cannot be allowed to walk upon flowers in carpets. You don’t find that foreign birds and butterflies come and perch upon your crockery; you cannot be permitted to paint foreign birds and butterflies upon your crockery.3

However, more sophisticated Christians throughout the ages have contented themselves with dismissing popular fantasy as a frivolity and therefore not deserving of serious notice. Moreover, despite hostility to the fantastic, Christianity did not quickly give rise to a realistic literary tradition, partly because it was also hostile to our fallen world and therefore could not consider realistic representations desirable or enlightening; partly, too, because it fostered allegory and other forms of fantasy deemed compatible with Christian morality. Marie de France can claim in the prologue to her lais that the fantastic adventures she describes conceal significant moral messages. Acceptable fantasy appears in the miracles stuffed into saints’ lives. Bede, who wrote the sober and realistic Lives of the Abbots, adds miracles to his source for his Life of Cuthbert, composing this fanciful story juxta morem, or according to the custom, of that particular literary form.4

Christian fantasy encouraged the non-real, but did not sharpen critical awareness of the phenomenon because fantasy, if it served the cause of morality, became “true” and therefore ethically distinct from the lies of fable. Even today, the vitae of the fictitious Saints George and Christopher are held to contain moral truth, despite their unhistoricality. Christianity did nothing to redress the balance between fantasy and mimesis, although Christian poets made much use of fantasy in allegory and romance and pious tale. At most, acknowledged fantasy was tolerated as nugatory entertainment, but it received no separate, positive status, with the result that fantasy continued to seem a fringe phenomenon.

Socrates’ repudiation of chimeras and pegasuses directed the attention of his successors away from fantasy’s richness as a literary impulse. He also deflected inquiry away from the relationship between fantasy and the unconscious, thus discouraging systematic analysis in that direction until psychoanalysis. Now, as we focus on the psychological validity and artistic effectiveness of fantasy, we must struggle to correct our distorted perceptions and invent the requisite critical vocabulary. Since our terms evolved to meet the needs of mimetic assumptions, only the mimetic elements in literature have hitherto worn faces. However, as we finally begin to recognize the presence of this faceless, silent partner, its form gradually grows more perceptible.

In the rest of this chapter, I will discuss the theories of fantasy which have recently been put forward, their strengths, their weaknesses, and the ways in which the theories complement or challenge each other. Then, when readers have had a chance to weigh the advantages of an inclusive definition against those of exclusive definitions, I will look more closely at the idea of fantasy as literary impulse, and will spell out the assumptions I make about the nature of literature. Throughout the present chapter, from different angles, I am trying to offer answers to the question “What is fantasy?” When we have some answers, we will be in a better position to consider the questions that inspire Parts II and III, namely, “How is fantasy used?” and “Why use it?”

Exclusive definitions

Ultimately, I shall argue that recent theories of fantasy work from faulty assumptions about the nature of literature, so let me outline what these premises seem to be. The recent theorists assume, along with Plato and Aristotle, that the essential impulse behind literature is mimetic, and that fantasy is therefore a separable, peripheral phenomenon. Viewing fantasy as separable and secondary has led these critics to try to create exclusive definitions. They assume that fantasy is a pure phenomenon, that a few clear rules will delimit it, and that the result will be a genre or form which can be called fantasy. They frame their definitions in such a way as to exclude as many works as possible. What remains, for most of these critics, is a small corpus of texts, all fairly uniform in their uses of departure from consensus reality, and this small corpus is duly declared to be “fantasy” – with little thought given to all the works that have departures from reality which somehow fail to fit the rules. The resulting definitions do delineate various minor strains in literature, but are incapable of telling us much about the larger problem of departures from consensus reality: their nature, their aims, their effects. We can be grateful for these many insights, but I feel we need to take a broader view. If we are to unify various disparate subfields of fantasy, we shall need an inclusive definition. But first let us see what contributions the exclusive definitions can make.

Comparing the explicit and implicit definitions of fantasy put forward by three such diverse critics as Harold Bloom, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Eric Rabkin is like trying to compare interferon, saffron, and platinum. All the substances are valuable, but we need a common standard against which to measure them, some kind of framework that will highlight their similarities and differences.

The framework I would like to offer is a diagrammatic model of literature in its context. Something like this scheme is propounded by M.H. Abrams in The Mirror and the Lamp:

Figure 1

Work, artist, and audience are self-explanatory. Universe is Abrams’ term for “nature”, or “people and actions, ideas and feelings, material things and events, or super-sensible essences”. This universe lies within the fictive work. Abrams uses his scheme to compare critical theories of literature. As he points out, “Although any reasonably adequate theory takes some account of all four elements, almost all theories … exhibit a discernible orientation toward one only.”5

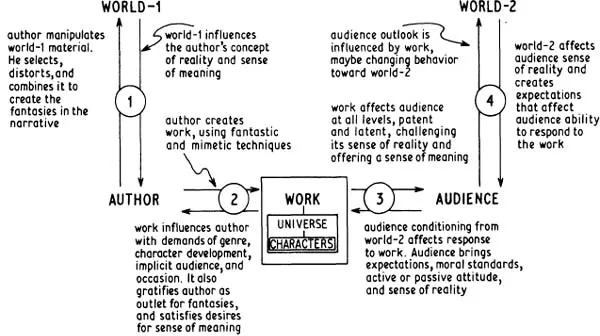

Author, work, and audience, as I shall call those same elements in my diagram, seem unexceptionable – they are necessary units in any communication situation – but “universe” is an oversimplification. First causes and final effects of a piece of literature are not confined to its author and audience. In addition to the universe within the work, we have to keep track of two other cosmoi in which those first and final effects are worked out – namely, the world surrounding the author (world-1) and that enfolding the reader (world-2). World-1 is everything outside the author that impinges upon him, consciously or unconsciously. It both reflects and shapes his scale of values. The elements an author creates with come from world-1. If the literature is especially successful, it makes its mark not just on members of the audience but, through them, on world-2, everything that impinges on the lives of members of the audience. These worlds of experience, world-1 and world-2, differ even if the artist and reader are contemporaries; world-2 indeed differs for each member of the audience. If artist and audience are separated by time, language, religion, culture, or class, the amount of shared reality may be small. The nature of what each considers significant reality will overlap even less. The universe or world within the work differs yet again. In order to compare theories of fantasy and see how they operate, we need first to be clear on the network of reciprocal relationships surrounding any work of literature. Hence, I propose the following diagram of a text surrounded by its successive contexts:

Figure 2

The descriptions labeling each arrow reflect my concern with fantasy, but the diagram is usable for discussing any critical orientation. Solid arrows indicate material covered by the critical theory; dotted arrows, as seen in figure 3 below, are areas that are lightly covered or only implicit; no arrow or parentheses around a blank indicate that the theory pays little or no attention to that part of the total system. The orientation of the arrows simply alludes to the direction of the relationship being discussed: “author←work” refers to the demands made on the author by the work through its generic conventions, and through the needs of the developing personalities of the characters. Within the work, I have labeled the third world “universe”, Abrams’ term for it, in order to reduce the confusion with worlds -1 and -2. Characters I treat as a sub-category within the fictive universe. They are part of that fictive universe, but some theories of fantasy make a distinction between the characters and their universe, so I mark them as separable.

One can use this scheme, for instance, to characterize the concerns of schools of criticism and thereby establish grounds for...