Overview

The intention of this monograph is to describe some experiments and theoretical developments in Pavlovian second-order conditioning that have come from my laboratory over the last few years. It is my belief that this work provides some interesting insights not only into Pavlovian conditioning but also into associative learning generally. Indeed, a major purpose of this volume is to argue that through the use of second-order conditioning one can address questions about Pavlovian associations that otherwise seem intractable.

However, it seems prudent to begin with a brief description of what constitutes second-order conditioning and a preview of why anyone should consider it worth investigating. In my view Pavlovian conditioning is best seen as an example of associative learning in which an organism learns the relation between two events in its environment. One of those events is normally of significance (the unconditioned stimulus [US]), whereas the other is normally of less importance prior to the learning experience (the conditioned stimulus [CS]). But as a result of exposure to a relation between those events, the organism is changed and exhibits that change by a modification of its behavior. The classic example, of course, is salivary conditioning in which the occurrence of the food US is signaled by some innocuous event such as the presentation of a tone CS; the result is that the learning of this relation modifies various aspects of the organism’s behavior, most notably endowing the tone with the ability to evoke salivation in anticipation of the food. But since Pavlov’s (1927) original observations, it has become clear that many events could substitute for the food and the tone, and many different relations could be arranged between the two events. Consequently, it has seemed plausible to many that Pavlovian conditioning could be taken as a model for associative learning generally, in which various relations are learned among various events.

Second-order conditioning represents one case of such learning in which a particular stimulus serves as the significant event in place of the US. In most Pavlovian experiments the significant event, the reinforcer, has its power innately, without the organism having any special individual experiences. The distinguishing feature of second-order conditioning is that its reinforcer is not of that sort; instead its reinforcer has that status only because of past learning experiences by the organism. Thus, in a typical second-order conditioning experiment the presentation of S2 signals that of S1, but S1 is of importance only because in the past it has signaled the occurrence of some US. So, for instance, in Pavlov’s original experiments, a metronome S1 was first paired with food, enabling it to evoke salivation. Then a black square S2 was followed by the metronome but not by food. In the present context, the learning of interest is that of the relation between the square and the metronome, indexed by the square’s acquiring the ability to evoke salivation. Because the square was never paired with the original food reinforcer but only with something that itself had been paired with that reinforcer, Pavlov thought of this as second-order conditioning.

But why should the occurrence of this second-order conditioning occasion any special interest? Historically, psychologists found this phenomenon of interest because it appeared to expand the applicability of Pavlovian conditioning as an account of behavior. Relatively few stimuli have innate significance for most organisms, and consequently only a small portion of behavior seemed attributable to the direct relations of other events with those stimuli. Thus, although many psychologists agreed that Pavlovian conditioning might serve as a model for associative learning, it was less obvious that it is directly responsible for much of the normal behavior of the organism. However, the phenomenon of second-order conditioning appeared to increase the range of behavior for which Pavlovian conditioning might be responsible. It does so by increasing the number of significant events through past experience. This argument seemed especially persuasive to those who would attempt the direct application of Pavlovian conditioning to the range of human behavior.

Without commenting on the validity of this argument, I doubt that it points to the real value of second-order conditioning. Instead, it seems to me that the primary virtue of second-order conditioning lies in its being a powerful tool for the study of associative learning. For this reason, most of this volume centers on the ways that one may use second-order conditioning to expose the nature of Pavlovian associations.

Any adequate understanding of associative learning must deal with three separable but intertwined problems. The first is to describe the circumstances under which associative learning occurs. What does it take to produce such learning? What relations among events promote the formation of associations? The second issue centers on the content of that learning. When associations are formed, what is associated with what? This is the classical “what is learned” issue. The third question has to do with performance. How does that learning generate changes in the organism’s behavior? Or, put from the experimenter’s point of view, what behavior can one use to index the occurrence of associative learning? These problems of circumstance, content, and performance are three basic ones that any theory of associative learning must address. In the subsequent pages, I argue that second-order conditioning importantly helps us approach each of these problems. In my view, it is for this reason that anyone interested in associative learning must attend to the phenomenon of second-order conditioning.

But before beginning to discuss in detail these virtues of second-order conditioning, I need first to comment on a historically nagging issue. That issue concerns whether, in fact, second-order conditioning is a real and powerful phenomenon. Although Pavlov reported its occurrence, he described it as transient. Subsequent authors have often been less than enthusiastic about its reality. There are two questions to be addressed here. First, is there any evidence that second-order conditioning occurs in sufficient magnitude to be useful? Second, what is the generality of its occurrence? I here describe two sample experiments that are intended to address directly the first question. Also to provide some evidence on the generality of second-order conditioning, they are selected from different conditioning preparations; but the question of generality is dealt with implicitly as different examples of second-order conditioning are described in subsequent chapters.

A Demonstration of Second-Order Conditioning

An experiment described by Rizley and Rescorla (1972), the first second-order conditioning experiment reported from our laboratory, serves as an initial illustration of the phenomenon’s existence. That experiment used a popular modern Pavlovian conditioning preparation, conditioned suppression with rat subjects. In that procedure a neutral stimulus (S1) is paired with an aversive US, in this case, electric shock to the feet. It is common to describe the outcome of the animal’s learning this relation as fear conditioning. Like many animals, rats exhibit their fear of painful events by becoming less active. Employing standard procedures, we pretrained the rats to engage in a regular activity, pressing a lever for food in a standard operant chamber. We could then use the suppression of that regular lever pressing as an index of its fear of various stimuli.

Table 1 shows the design of the experiment that employed this conditioning technique. The group of principal interest (PP) received first 8 pairings of a 10-sec light with a 1-mA .5-sec footshock, with the intention of producing first-order fear conditioning of the light. Once the light had become capable of producing suppression of the ongoing lever pressing, these animals received 6 pairings of a 30-sec 1800-Hz tone with the light, in the absence of further footshocks. Here the intention was to use the light to establish second-order fear conditioning to the tone. The data of interest are the suppressions during that tone, because those indicate the success of that conditioning.

TABLE 1 Design Used by Rizley and Rescorla (1972)

| Group | Phase I | Phase II |

|

| PP | Light → Shock | Tone → Light |

| PU | Light → Shock | Tone / Light |

| UP | Light / Shock | Tone / Light |

Groups PU and UP were included for the purposes of interpreting the suppression expected in Group PP. Group PU received paired presentations of light with shock but then unpaired presentations of the tone and light. The intention of this group was to discover whether the suppression anticipated in Group PP depended on the pairing of tone and light. It is only when behavior changes depend on such a relation that we would normally speak of the occurrence of conditioning. If the tone produced suppression whatever its relation to the light, we would not normally attribute that suppression to the animal’s learning any particular relation. Rather, we would interpret it in terms of some “nonassociative” process dependent only on the separate event presentations. Consequently, comparison of Groups PP and PU is important for the conclusion that conditioning has been observed in Group PP.

Group UP was included to be sure that this conditioning is second-order in character. That group received tone-light pairings but their light had never been paired with shock; instead it had been presented in an unpaired relation to shock. That group is important to the conclusion that the light’s reinforcing power depends on its own conditioning history. It is quite possible that the light could condition fear to the tone without itself ever having been paired with the shock. But in that case, we would think of the suppression to the tone in Group PP as a case of simple first-order conditioning, with the light serving as the US. Consequently, comparison with Group PU allows an assessment of the importance of the previous light-shock pairings. Hence, it helps us identify the outcome in Group PP as an example of second-order conditioning.

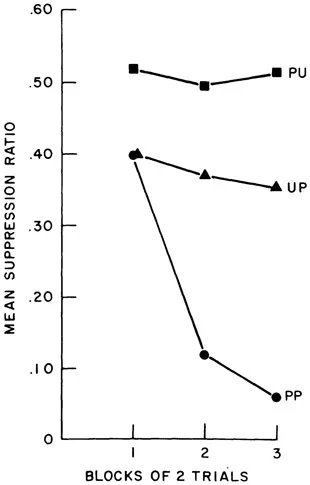

FIG. 1. Second-order conditioning of suppression during a tone S2. In Group PP, a light S1 had previously been paired with shock and then presented following S2. Groups UP and PU omitted either the S1-shock or the S2-S1 pairings. (From Rizley & Rescorla, 1972. Copyright 1972 by the American Psychological Association. Reprinted by permission.)

Figure 1 shows the outcomes of these operations. The results are plotted in terms of a suppression ratio index for the various second-order conditioning trials. That ratio compares the response rate during the tone with that in a comparable period prior to the tone onset. Since it has the form A/(A + B), where A and B are the response rates during and prior to the tone, respectively, that ratio yields a value of zero when the tone is highly suppressive and one of .5 when it fails to disrupt the ongoing lever pressing. The finding of principal interest is that the animals in Group PP rapidly came to suppress their behavior during the tone. By the end of six conditioning trials, that tone almost totally disrupted ongoing lever pressing, a result comparable to that expected had the tone been paired directly with a mild shock. The greater suppression in Group PP compared with either of the other groups suggests that both the light-shock and the tone-light pairings were of importance. That is, this suppression may be taken as evidence of substantial second-order conditioning of fear.

But it is also of interest to note that Group UP showed some evidence of suppression, perhaps suggesting that indeed the light had some significance of its own, even without being paired with shock. That observation points to the importance of including controls like those employed here; one cannot count on the causal identification of an event as neutral in carrying out second-order conditioning experiments. Regardless of the unconditioned properties of this light, it is clear that substantial second-order conditioning of the tone was observed.

A Second Demonstration

Lest it be thought that such substantial second-order conditioning is confined to the disruption of behavior generated by potent aversive outcomes, I also display the results of an experiment using appetitive events. This experiment used an activity conditioning preparation originally developed by Sheffield and his collaborators (e.g., Sheffield & Campbell, 1954). In that preparation, hungry rats are given Pavlovian pairings of neutral stimuli with the delivery of food pellets. As they learn that relation, the rats become quite active during the CS; consequently, one may use changes in their activity as a measure of their learning the CS-food relation. This general phenomenon is one that has been casually observed by many experimenters who have maintained a colony of hungry rats. The colony may be a quiet place until the caretaker enters; at that time it will suddenly erupt into a good deal of activity. The reason, at least in part, is that the caretaker’s responsibility for feeding the animals has resulted in his being a Pavlovian signal of food. The rats display this knowledge by becoming active in his presence.

Holland and Rescorla (1975b) adapted an apparatus for measuring this activity. The device consisted of a standard operant chamber with its lever withdrawn, in which we could present lights and tones, as well as deliver food. The chamber was mounted on the upper of two horizontal plates that were separated by ball bearings. Suspended from the top plate was a metal plumbob that hung in the center of a metal ring. Whenever the animal moved about, the top plate moved with respect to the bottom plate, causing the plumbob to strike the sides of the ring. We simply electrically recorded those contacts and used their frequency as a measure of activity. This proved to be a crude but highly effective device.

With this procedure, we employed a three-group experimental design like that sh...