1. Introduction

I have gradually acquired the belief that the alternative lies in the unfinished, in the sketch, in what is not yet fully existing. The ‘finished alternative’ is ‘finished’ in a double sense of the word.

If it is correct, this view has considerable consequences for political life. It means that any attempt to change the existing order into something completely finished, a fully formed entity, is destined to fail: in the process of finishing lies a return to the by-gone. Note that I am here thinking of change and reversion in terms of structure. The existing order changes in structure while it enters its new form. This was the meaning of the oracles: they provided sketches, not answers, as entrances to the new. This is the meaning of psychotherapy. In the sketches of the oracles and of the therapist to him who asks and to the patient – in the very fact that only sketches are given – lie their alternatives.

Existing order changes in structure while it enters the new. The first political question, then, becomes that of how this ‘while’ should be started, how the sketch should be begun, how it should be mobilized.

The second question, which is politically almost as central, is that of how the sketch may be maintained as a sketch, or at least prolonged in life as a sketch. An enormous political pressure exists in the direction of completing the sketch into a finished drawing, and thereby ending the growth of the product. How can this be avoided, or at least postponed? The answer to this question requires a new understanding of the social forces that work for the process of finishing.

Through both of these questions, abolition runs like a red thread. Abolition is the point of departure.

In the following I shall first explain in more detail why the alternative lies in the unfinished. Next, I shall approach the two questions mentioned above: the inception and the maintenance of the unfinished. I will hardly give complete answers to these questions, but I hope to be able to give some suggestions.

2. The unfinished as alternative

The alternative is ‘alternative’ in so far as it is not based on the premises of the old system, but on its own premises, which at one or more points contradict those of the old system. In other words, contradiction is a necessary element in the alternative. It is a matter of contradiction in terms of goals, or in terms of means together with goals.

The alternative is ‘alternative’ in so far as it competes with the old system. An arrangement which does not compete with the old system, an arrangement which is not relevant for the members of the old system as a replacement of the old system, is no alternative. I emphasize that the concept of competition takes, as its point of departure, the subjective standpoint of the satisfied system-member being confronted with an opposition. The political task is that of exposing to such a member the insufficiency of being satisfied with the system. When this is exposed, the opposition competes. This is the case whether the system-members in question are on top or at the bottom of the system. Often those we try to talk to will be at the bottom, because these are considered more mobile for actual political action. The main problem, then, is that of obtaining the combination of the contradicting and the competing; the main problem is that of avoiding that your contradiction becomes non-competing and that your competition becomes agreement. The main aim is that of attaining the competing contradiction.

*

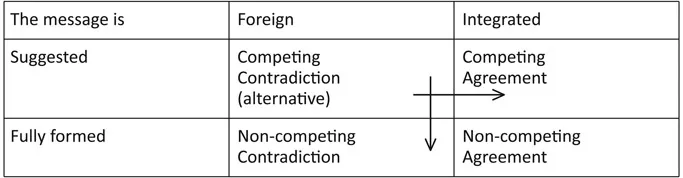

An opposition may seek to bring a message which is (1) foreign and (2) fully formed. In the subsequent discussion, the fact that a message is ‘foreign’ will mean that the message in fact does not belong to, is not integrated or woven into, the old system. The opposite of being foreign will subsequently be that of being ‘integrated’: the message one seeks to bring has in fact already got its defined place, integrated into the old thinking.

The fact that a message is ‘fully formed’ will subsequently mean that the consequences of the actual carrying-out of the message are clarified, or approximately clarified. The opposite of being fully formed will in the following be ‘suggested’: the consequences of the actual carrying out of the message are not yet clarified.

The opposition that speaks (1) in a foreign way and (2) in a way that indicates a fully formed message, thus brings a message (a) which does not belong to, is not integrated in, the old system, and (b) which at the same time is clarified in so far as the consequences of its actual practical carrying-out are concerned. The contradiction of this opposition stands in danger of becoming non-competing. Since it is clear – beyond doubt, definite – that the message, when carried out, does not belong to the old system, the satisfied member of the old system may disregard the message as of no importance to himself and his system, as irrelevant, as of no concern to the system. The contradiction of the opposition may be disregarded as permanently ‘outside’, and thereby be set aside, because it is beyond doubt that the message does not belong to the established system.

The message which is foreign and fully formed thus contains a contradiction, but the contradiction easily becomes non-competing. This analysis, of course, is couched in ideal-typical terms. Some parts of the Marxist- Leninist opposition in today’s Scandinavia possibly constitute an example which approaches the ideal type. Let us for a moment take a look at the opposite extreme: the message with a content (1) which in fact is woven into, or integrated in, the old system, but (2) where the content is only suggested, so that the consequences of the actual carrying-out of the message remain unclarified. This message will not so easily be written off as non-competing. Since the question of what the message will lead to is not clarified, the message cannot simply be set aside. But at the same time the message does not contradict the establishment. In fact, it is integrated into, and therefore in accordance with, the premises of the old system. In sum, the message constitutes what may be called a ‘competing agreement’, a fictitious competition. Do there exist examples which approach such a combination of characteristics?

Perhaps ‘the meditating conservative’ may give an example approximating to how a message which is integrated and suggested becomes a ‘competing agreement’ (the concept of competition all the time being defined from the point of view of the satisfied system member). The pipe-smoking, casually philosophizing district attorney in an exclusive interview with the Sunday newspaper may be a case in point. Nothing new is being said, but the old is stated in such a way that the reader is given the impression of interesting depth. Competition takes place – about nothing.

*

Above I have first discussed how a contradiction may become non-competing (because it is fully formed), and afterwards how an agreement may become (fictitiously) competing (because it is only suggested). What we are searching is the alternative, the competing contradiction. The important thing at this point is that neither of the two cases discussed above provides an understanding of the alternative.

Logically there are two other main possibilities.

The first is that of (1) the integrated and (2) fully formed message. The main thing to say about the integrated and fully formed message is that this is a message which brings nothing new. The integrated and fully formed message constitutes what we may call a non-competing agreement. The ‘able’ student reproducing textbook material from rote learning is probably the core example. This student does not give any hint of an alternative. His examination paper contains no contradiction, and no message experienced as competing. It contains only memorization. The sociologically significant point is that considerable parts of life in our society consist of such reproduction or non-competing agreement, interspersed by a few meditating district attorneys.

The remaining possibility is that of (1) the foreign and (2) suggested message. Here we are faced with a contradiction, and finally at the same time competition. The unclarified nature of the further consequences of the contradiction makes it impossible for the (satisfied) system member to maintain that the contradiction is certainly outside his realm of interest. Contradiction and competition are united – in the alternative.

This is at the same time the definition of ‘the unfinished’. To be sure, the foreign and fully formed message is unfinished in the sense that it is outside the established – empirically tested and tried – system, but it is at the same time finished in the sense that its final consequences are clarified. The integrated and suggested message is in fact fully tried out, and thereby finished, even if its consequences are unfinished in the sense of not being set down on paper. The integrated and fully formed message is finished in a double sense of the word: it is in fact fully tried out, and its consequences are even clarified, on paper. The foreign and suggested message, however, is unfinished in the sense that it is not yet tried out as well as in the sense that its consequences are not yet clarified. Thus, the alternative constitutes the double negation of the fully formed or finally framed world.

The alternative contradicts the vulgar interpretation of Wittgenstein’s closing words in Tractatus: ‘Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muss man sehweigen.’ The vulgar interpretation of this statement, which I interpret as positivism – the tested and fully formed – in a nutshell, claims (as far as I can understand) that we simply must remain silent unless our message is: (1) foreign and fully formed, (2) integrated and suggested, or (3) integrated and fully formed. But thereby the alternative is also omitted: (1) Either the deviant is rejected as non-competing, (2) or we introduce something which is only fictitiously deviant, or (3) we only repeat what is already established. Wittgenstein’s positivistic followers do not allow the fourth possibility: we are not allowed to talk in a foreign and suggestive way; rather than doing so, we must remain silent. However, it is vitally important to insist on the fourth possibility, and in this sense be negative rather than positive; it is vital not to remain silent concerning that which we cannot talk about; it is vital to express the unfinished.

But it is very difficult. I shall return later to the forces we must fight against. First, I shall give some concrete examples of the unfinished, and thereby of the alternative.

Love is an unfinished relationship. In its state of being unfinished, love is boundless. We do not know where it will lead us, we do not know where it will stop; in these ways it is without boundaries. It ceases, is finished, when it is tried out and when its boundaries are clarified and determined – finally drawn. It represents an alternative to ‘the existing state of things’: to existence in resigned loneliness or in routinized marriage. Resigned loneliness and routinized marriage are not alternatives in relation to each other: contradiction as well as the degree of competition are low, if at all present. (But unfinished loneliness, in which we are en route to something through the loneliness, and in which boundaries are not drawn, may certainly be an alternative to – contradicting and competing with – routinized marriage.)

The treatment experiment is an unfinished state while it is being developed. While being developed, it is non-integrated as well as without boundaries; the question of how narrowly the boundaries may be drawn is not determined. The very unfolding of the experiment, the development of the project, is an alternative to the established state of things – for example to hospitals and prisons. In its approximate boundlessness, the experiment contradicts and competes with the established structures. The content of the experiment, in the form of concrete ‘treatment method’, is close to immaterial; the most important thing is the process of development of the project. In line with this, experience shows that as the pioneering period of the treatment experiment ceases, as wondering withers and boundaries are drawn, and as continuation for its own sake becomes the issue, the new experiment is simultaneously incorporated in the establishment. What is strange is that we rarely act in line with this. We rarely view the ‘pioneering stage’ as life itself; rather we tend to view it as ‘only a beginning’.

The third and most encompassing example concerns the notion of the ‘alternative society’. Contradiction to and competition with the old society lies in the very unfolding of ‘the alternative society’. Contradiction to and competition with the old society lies in the very inception and growth of the new. The unfolding of the new may take place after a revolution, after a war, after a physical catastrophe. The alternative society, then, lies in the very development of the new, not in its completion. Completion, or the process of finishing, implies full take-over, and thereby there is no longer any contradiction. Neither is there competition.

3. The forces pulling away from the unfinished

As I have indicated earlier, the forces which pull away from the unfinished – away from the competing contradiction – are many and strong. We must say something about these forces as a background for our considerations about the inception and maintenance of the unfinished.

Figure 1 schematically presents the material we have covered so far. The Figure is introduced in order to simplify the presentation that follows. The forces that pull away from the unfinished – away from the competing contradiction – move in two directions, as the arrows show.

Figure 1 The forces pulling away from the unfinished

In the first place, there are forces which finish in such a way that the contradiction becomes non-competing; in such a way that competition is abolished. The vertical arrow shows this movement. Language provides a road to it. The pressure in the direction of finalizing language, the pressure in the direction of clarifying what we mean, may lead to a contradiction in this direction. When language is finalized, the answer is given, and the contradiction – though stubbornly maintained as a contradiction – is finished in the sense of becoming fully formed. When fully formed, the foreign language may be rejected, and is rejected, as clearly and definitely of no concern.

But the forces making a contradiction non-competing are, relatively speaking, not so strong. Far stronger are the forces that abolish the contradiction, the forces that change the contradiction to an agreement rather than making it non-competing. The horizontal arrow shows this finishing movement. Why are these forces stronger? The main reason is probably that to those working for the new, non-competition seems more dangerous than agreement. First of all: non-competition – when others act as if one’s message does not exist – gives little hope of effect. Agreement, on the other hand, gives greater subjective hope. Even if the issue here actually is that of surrender from the side of those who are working for the new, we can fool ourselves into believing that surrender takes place from the receivers’ side, and that the receivers agree to the new message.

In the second place, as the concept is used here, non-competition is no relationship. Non-competition therefore seems irrevocable and irreversible. Agreement, on the other hand, is a social relationship, an interhuman interaction. As interaction it is a process, and we therefore easily imagine that our own surrender and agreement may once again be altered into contradiction when this appears necessary. The following sections will hopefully suggest that in reality, this is close to impossible.

Language is important also with regard to the doing away with the contradiction and its change into agreement (rather than the maintenance of the contradiction and its becoming non-competing). To amplify, in a specific and important way, language is related to power. Those in power decide (by and large) what language is to be spoken. The opposition is not in power, and in order for the opposition to ensure that it is defined as a competing party, it must begin to speak the language of those in power. But language not only provides a possibility for transmitting information. It is also active in structuring and defining the problem at hand. The more we use the language of the powerful, the more attuned we become to defining the problems at hand as the powerful usually do; in other words, the more integrated we become into the old system. We define the problems at hand in this way in order to persuade the powerful that our contradiction is sensible. But competition is then maintained at the cost of the contradiction itself; the contradiction is abolished and turned into fundamental agreement; the forms which compete are both integrated into the old system, tested out, and finished.

I will give an example. In penal policy there is, from the side of one opposing group, a stress on the use of ‘treatment’. To the opposition, the concept of ‘treatment’ has a professional and specific meaning, and treatment is in itself a goal, though a part of a means-end chain. To make the concept understood and competing, the opposition characteristically translates it into the language of the ruler. For example, the opposition tries to talk of ‘influencing’, or ‘persuading’, the ‘deviant’. In doing so, however, the opposition has straight away defined the issue as the other party – those in power – usually does. To the other party, the goal is that of creating better ‘morals’, and the concept of treatment has now been defined in these terms. When the lawyers in the Prison Department have finally understood, those who are out of power – those in opposition – have finally managed to express themselves perfectly in the language of those in power. And at the same time, the contradiction is gone; the problem at hand is defined according to the usual standards of the powerful.

Here competition as well as contradiction will often disappear, because the language of the powerful is also fully formed or finished rather than just suggestive, and in the end we are thus confronted with a non-competing agreement, a nodding, rote-learning candidate. In the following discussion, however, I shall take one thing at a time, by assuming an element of (fictitious) competition between forms which are integrated and not in contradiction.

The general type of competition which I have discussed above is that of ‘persuasion’. Representatives of the new message seek, as their point of departure, to ‘persuade’ the representatives of the old system to replace the old way of stating the problem by a new one. For reasons given above, persuasion must take place in the language of the representatives of the established system, so that agreement about, rather than contradiction to, the tested – finished – way of stating the problem is established.

‘Persuasion’ is one of three important (perhaps not exhaustive) types of competition. The second type is ‘the example’. While ‘persuasion’ is linguistic, the ‘example’ is a matter of practice. The representative of the contradiction is challe...