![]()

1 Introduction to adaptation to climate change through water resources management

A systems approach

Elena Lopez-Gunn and Dominic Stucker

Introduction, research question and goals

This book presents evidence of the emerging wealth of knowledge and experience on adaptation to climate change from across the world. Adaptation is inherently local in both processes and outcomes, as compared to mitigation which is a global commons problem. The raison d’être for this edited volume is for diverse young and established researchers to add to this growing body of evidence, drawing from all continents and climates, from the most arid and water scarce countries to arctic environments; from countries with well-established and sophisticated policies on adaptation, to fragile states and border regions; from large, complex basins, to rural communities. What emerges is a picture of adaptation as the iterative application of learning in the face of change. The systems-based theoretical framework we present helps us draw out key barriers and bridges to adaptation through water resources management from this volume’s diverse and global case study chapters.

Analysis of our 20 case studies complements the outcomes from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which gives weight to the increasing relevance of adaptation (IPCC, 2014). Research and experience demonstrate that climate change and variability is mediated primarily through water: changes in rainfall patterns, increasing glacial melt, more frequent and intense droughts and floods, evaporation from soils, sea level rise, etc. Impacts can degrade the environment, deepen existing inequalities and compromise natural capital-dependent livelihoods. By presenting and examining a global set of case studies, our research seeks to identify some of the highest leverage strategies for adaptation. Climate change brings heightened risks for communities and institutions, but also an opportunity to build capacity to adapt through water resources management, while addressing environmental degradation, inequalities and insecure livelihoods.

Our research approach was both inductive and deductive: inductive in that the chapter proposals and inputs came from contributors, deductive in that a common theoretical frame was provided to support analysis and to structure knowledge emerging from the case studies. The choice of topic is centred on adaptation through water resources management because water is seen as central to adaptation in two respects: first because many impacts are related to water (floods, sea level rise, droughts, etc.) and second because water and adaptation are both largely local or regional affairs, where bottom-up knowledge has particular value. As editors, we wanted to explore this important niche, sharing experiences under a common analytical frame of adaptation to climate variability and change, viewed through the water lens. Across all case studies, we asked contributors to consider our central research question:

What are the key barriers and bridges for adapting to climate change impacts through water resources management?

Thus, our book’s goals are to:

• discuss and analyse capacity for adaptation to climate change in the water sector across a diversity of case studies through the themes of environment, equity and livelihoods; and

• analyse case studies to identify high leverage adaptation strategies, in particular paradigms and mindsets that underpin them and recommendations going forward.

Water rights, water pricing, water planning, building on local knowledge and encouraging collective action are all discussed by contributors, representing rich entry points for adaptation. The challenges we face, however, are commensurate. If adaptation policies are well designed, they can produce multiple benefits. Just as climate change can amplify vulnerability, the policies, resources and projects that result offer new avenues for action toward equity and sustainability.

Defining key themes and processes

Our overarching research question on climate adaptation is explored in a diversity of settings across the themes of environment, equity and livelihoods. These indicators, defined here, help describe the local state in each case study:

Environment is the state of the natural and physical capital and ecosystem services that underpin livelihoods and wellbeing.

Equity is the state of the social, political and financial capital that does or does not allow for access to and distribution of resources.

A livelihood is secure when it can ‘cope with and recover from stress and shocks, maintain or enhance its capabilities and assets, and provide sustainable livelihood opportunities for the next generation’.

(Chambers and Conway, 1992)

We borrow our definitions of key processes from the IPCC:

Adaptive capacity is the potential or ability of a system, region, or community to adapt to the effects or impacts of climate change. Enhancement of adaptive capacity represents a practical means of coping with changes and uncertainties in climate, including variability and extremes. In this way, enhancement of adaptive capacity reduces vulnerabilities and promotes sustainable development.

(Smit and Pilifosova, 2001)

Adaptation is adjustment in ecological, social, or economic systems in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli and their effects or impacts. This term refers to changes in processes, practices, or structures to moderate or offset potential damages or to take advantage of opportunities associated with changes in climate. It involves adjustments to reduce the vulnerability of communities, regions, or activities to climatic change and variability.

(Ibid.)

Mitigation is an anthropogenic intervention to reduce the sources or enhance the sinks of greenhouse gases.

(IPCC, 2001)

Exploring adaptive capacity

Adaptation would make development strategies robust to climate change, particularly when favouring proactive over reactive strategies (Shalizi and Lecocq, 2009). These strategies, in turn, are very dependent on the degree of local vulnerability to climate change impacts, defined as a function of exposure, sensitivity and adaptive capacity.

In this edited volume, contributors discuss concrete examples of adaptive capacity, which varies significantly across systems, sectors and regions. Through locally grounded experiences, contributors build our knowledge base of adaptive capacity – where there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach (Vincent, 2007) – to help inform the design of locally appropriate adaptation strategies. Though adaptation strategies vary from one place to another, this evidence grounded in first-hand knowledge and research can help us better understand adaptive capacity and identify barriers and bridges to adaptation.

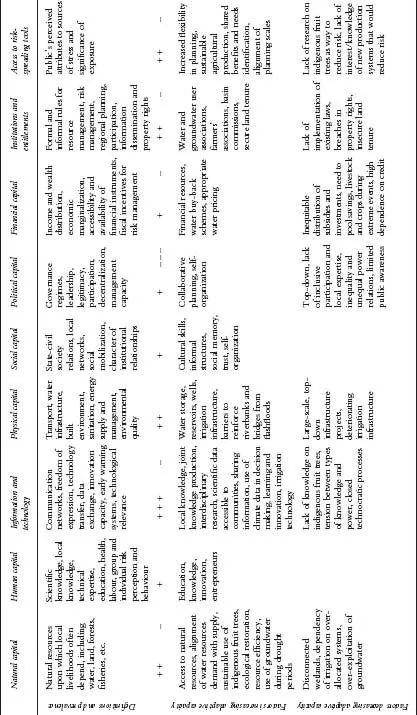

Table 1.1 is an elaboration on a compilation of key forms of capital that underpin adaptive capacity, including their prevalence across case studies and examples that increase and decrease specific forms of capital.

Building on past research, evidence from our twenty case studies offers two additional findings on the determinants of adaptive capacity. First, several case studies identify the importance of natural capital itself as a factor of adaptive capacity. Second, we recognize the fundamental importance of information flows and knowledge for adaptive capacity, and thus an indication that investment in this area could have great multiplier effects for adaptation.

Table 1.1 Determinants of adaptive capacity across case studies

Source: authors’ elaboration on Smit and Pilifosova (2001), Yohe and Tol (2002), Brooks et al. (2005), Eakin and Lemos (2006) and Bolson and Treuer (this volume).

Meanwhile, in relation to factors that decrease adaptive capacity, there are again two relevant findings: contributors did not recommend large-scale water infrastructure (often the source of much discussion and funding, e.g. through National Action Plans for Adaptation), while several did discuss alternative green infrastructure or ecosystem-based approaches. Furthermore, contributors clearly identified the lack of political will and the uneven distribution of financial capital and social equity as some of the factors that can most undermine adaptive capacity. Such distribution (or lack thereof) has a central positive or negative impact on vulnerability.

Theoretical framework: a systems approach

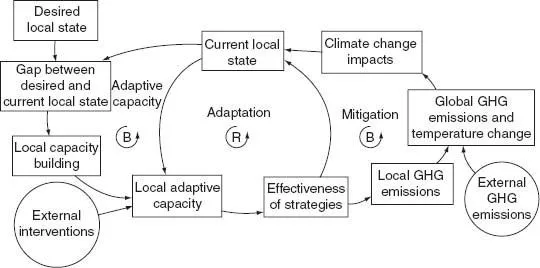

We have taken a systems thinking approach to our book, offering contributors a causal loop diagram, below, as a tool for analysis (Figure 1.1). We have intentionally kept the theoretical framework simple to be applicable in a variety of local settings. We offer an expanded version of the framework in our conclusion chapter, incorporating feedback and results from contributors.

To facilitate interpretation of the theoretical framework, we introduce several systems thinking terms below (in italics and in Box 1.1). Boxes represent key stocks that can be increased or decreased through a range of flows, the connecting arrows. In our diagram, the environment, for example, is an important component of the current local state stock. While the environment can be degraded by climate change-exacerbated floods or droughts, it can also be regenerated through effective adaptation strategies.

Figure 1.1 A theoretical framework for local adaptation to climate change (source: authors).

Box 1.1 Systems terms in theoretical framework

Stocks | □ |

Flows | → |

Reinforcing loops | R |

Balancing loops | B |

Stocks and flows are connected in loops, often meaning that X influences Y, but that Y also influences X. There are two kinds of feedback loops: reinforcing and balancing. The reinforcing loops drive change in a system, for better or worse. For example, the adaptation loop in the diagram above is reinforcing: when environment, equity and livelihoods are compromised, adaptive capacity decreases, as does the effectiveness of adaptation strategies, perpetuating decline in the current local state. The adaptation loop can, of course, bring about change for the better when adaptive capacity is increased.

The other kind of loop is balancing, a process that seeks stasis in the system. The adaptive capacity loop is an example of this balancing loop, as it tries to make the current local state become synonymous with the desired local state. As the current local state improves, the gap between the desired and current realities narrows, decreasing the need for local capacity building. As the need for adaptation decreases, adaptive capacity and the effectiveness of adaptation strategies plateau. In this scenario, we have either mitigated climate c...