![]()

1 Slavery Heritage and the Call to Home

Diasporan Travel to Ghana

A SENSE OF PLACE: CAPE COAST, GHANA

As soon as I stepped down out of the plane, I was reminded how hot Ghana can be. What was a comfortable pair of jeans on the flight across the Atlantic suddenly became oppressive in the heat and humidity. My Ghanaian research assistant and host, Paa Kwesi,1 greeted me at Accra’s Kotoka International Airport, and we wasted no time in driving the three hour journey to the sleepy town of Cape Coast (Oguaa in the local Fante dialect).

Cape Coast is the capital of the Central Region and has a population of 170,000, a figure that seems too high but includes dispersed areas further afield from the city center. Its economy is based on petty trade, fishing, secondary school and tertiary education, municipal government, and tourism. Cape Coast is a fascinating mix of the old and the new, the natural and the human-made: the contrast between the red earth and the green grass is visually stunning; fishermen ferry their wooden canoes out to sea against the rough waves near the castle; sometimes Fulani herdsmen direct their cattle around town in the midst of heavy traffic; the sounds of the crashing waves and chirping insects overpower those of speeding cars at night.

The town’s rich African and colonial pasts intermingle in its architecture and place names. The open-air market selling foodstuffs and household goods is called Kotokuraba, meaning “crab stream” and signifying the large supply of crabs that were historically trapped and sold in Cape Coast. In the early 1990s, a crab monument (Oguaa Akoto) was erected in the heart of town by Cape Coasters living in Accra (see Figure 7.2). Near this statue is the modest London Bridge. Closer to the coast but still within walking distance is Victoria Park, a public fairgrounds used for durbars (festivals) complete with a bust of the British monarch. Not far from this park is Emintsimadze Palace, where Cape Coast’s traditional chiefs meet to conduct official business. A bit further inland but still close by, Chapel Square is a central gathering space and reference point in front of Wesley Methodist Church. Nearer to the coast is Cape Coast Castle, the enormous heritage tourism destination that was once a trading fortress. It was here in 2001–2 that I spent much of my time engaged in deep hanging out (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Cape Coast, Ghana. Cape Coast Castle in the background and Chapel Square in the foreground. Photo by author, 2002.

In spite of the mid-afternoon heat and humidity, the mood at Nakus store outside Cape Coast Castle was jovial. The handicrafts traders and snack sellers were chatting with the castle workers who signed in car owners when they parked right outside the grounds. New highlife music was playing on the radio next to Blankson and me as we quenched our thirst with Sprites, wiped our foreheads with our handkerchiefs, and talked about how my fieldwork was progressing. I mentioned that I was expecting two American visitors and asked if he would be our tour guide. He enthusiastically agreed. The castle just across from us was a gigantic, bright white structure dominating the landscape flanked by local Ghanaian fishermen paddling out to sea on one side and the Castle Restaurant serving tourists and well-to-do Ghanaians on the other.

Adolescent males whom Ghanaians refer to as small boys hung out on the path between the castle and the restaurant, greeting visitors, asking for addresses and money, and occasionally selling necklaces and bangles. When there were too many boys or if they were deemed too aggressive, the castle’s security guards chased them away. Cars careened past us and people walked by, going about their day-to-day activities like selling rock buns or fetching water. Black crows flew overhead as the breeze ruffled through our clothes and blew around the fronds of the nearby palm trees. One of the traders took a break from playing the dice game ludo as he shooed a small herd of sheep away from the kiosks featuring wood carvings, beads, and leather goods from the North.

After having lived in Cape Coast continuously for ten months and having spent the previous two summers there, I was acquainted with mobile CD traders, taxi drivers, and the women who grilled delicious tilapia outside the chop bar a short walk from my Ghanaian family’s house. Several knew me by name, and I suspect I was somewhat of a novelty to them as a young, white woman who spoke the local Fante dialect, drove around in a beaten up Opel, and stayed much longer than most abrafoɔ (foreigners). A few days after visiting with Blankson outside the castle, a Nigerian trader who sold CDs out of his duffel bag greeted me with, “Oh, you have strangers here.” Self-conscious about how this might come across to my African American guests, I responded by suggesting, “Yes, I have some visitors.” I had met Amani, a chiropractor working in Kumasi, through mutual American friends living in Ghana. Her mother, Edie, was visiting from the US, and they asked me to take them around to see the sights in Ghana’s Central Region. We had already spent the previous day at Kakum National Park and the crocodile pond at Han’s Cottage. Next on the agenda was a tour of Cape Coast Castle.

A large, white sign alerted passersby that Cape Coast Castle is a UNESCO World Heritage site, which features two museums, dungeons, and a museum shop. Cannons and mortars lined the entrance—three on either side and two in front. We walked down the path to the admission desk, greeting the security guards on our way. After waiting a few moments, Blankson appeared and ushered us over to the marble plaque at the entrance of the Male Slave Dungeon. He started the tour as he always does—by reading its inscription aloud:

IN EVERLASTING MEMORY

OF THE ANGUISH OF OUR ANCESTORS

MAY THOSE WHO DIED REST IN PEACE.

MAY THOSE WHO RETURN FIND THEIR ROOTS.

MAY HUMANITY NEVER AGAIN PERPETRATE

SUCH INJUSTICE AGAINST HUMANITY

WE, THE LIVING, VOW TO UPHOLD THIS.

This act calls attention to the sentiments found in the plaque and sets the mood for the tour. From the onset, visitors are invited by tour guides both directly and indirectly to imagine the historical events that took place at the castle. The act of reading the inscription indicates the proper level of reverence those on tour should exhibit, while drawing the visitors in to empathize with those individuals taken unjustly to be sold as slaves across the Atlantic. The overall message contained in the plaque is one of redemption: for descendants from the diaspora to find their homeland as a necessary act of self-realization and for all people to learn from and act upon lessons from history, vowing not to repeat the same mistakes made during the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

As we descended the ramp to the underground chambers used to store African men, Blankson turned out the lights to simulate conditions endured by slaves. There was only one window for light and ventilation. As we entered the first chamber on the right, he described how human feces, blood, and decomposed bodies formed the floor of the Male Dungeon. A long, narrow gutter etched into the floor was the only means used to divert waste from the cell. Blankson said, “If walls could speak, they would tell you what happened here. They were the witnesses to this inhuman treatment here for years.” We could smell the dank, humid stench, feel the lack of ventilation and light, and see the dismal state of the dungeons. Shocked by the deplorable living conditions she imagined for captives held there, Edie asked how many slaves were kept in the Male Dungeon. Blankson replied that 1,000 to 1,500 people crowded into the dungeon for up to three months at a time. He ushered us down the hallway towards another room that had been used for sorting captives. The wall before us used to be the entrance to an underground tunnel but was sealed in 1834 after the British had abolished the slave trade. Now the wall was covered with a white cloth. In front of it stood three white concrete steps adorned with goat skins, schnapps bottles, and bowls. This was the Nana Tabir shrine. Said to have been used for traditional religious rituals before the castle was built, it had been removed from the castle under the British, and was brought back. These days, a Ghanaian caretaker conducts healing rituals primarily for diaspora African visitors who reciprocate with dashes of 2,000 cedis here and there.

Blankson escorted us out of the dark dungeon, and once outside, he pointed out the irony that a church once existed on top of the dungeon. Edie, in disbelief, said, “How could they pray to God and treat human beings that way?” We walked a few steps further, but still within view of the dungeon and former church, to four marked graves. One of them belonged to Philip Quaque, the son of a wealthy local slave trader who had been sent to England to be ordained as an Anglican priest. He returned to Cape Coast to convert fellow Africans to Christianity and was responsible for establishing a school in the castle in 1766.

We walked up some steps and along the promontory lined by dozens of cannons pointing towards the Atlantic. Blankson mentioned that different European trading companies and pirates tried to capture the castle. He cited a case from 1722 when an English pirate and some of his men were killed. The rest were sent to the Caribbean to work as overseers on plantations.

In the courtyard overlooking the storehouses, Blankson explained that both incoming goods—guns, gun powder, alcohol, cloth—and outgoing commodities—slaves, gold, ivory—were kept there. Above the storehouses were the rooms reserved for merchants and officials to socialize, and above that was Palaver Hall, where business meetings were held and slaves were auctioned. Blankson explained that merchants would apply palm oil to the skin before a slave was branded so that the mark would be clear. We turned around and walked towards the Door of No Return. Along the way, we stopped at the Female Dungeon, where Blankson described how people between the ages of ten and forty were taken as slaves. The captives’ hair was shaved and their skin was rubbed with palm oil to make them look healthy and to facilitate sales. Blankson added that officials hand-picked women from the dungeon to rape. Those who were found pregnant while living in the castle were removed and allowed to deliver their babies in town. Their babies stayed, while the women had to return to the castle to be sold into slavery.

Blankson directed us down the short distance through the door to the ocean air outside. We could see young men paddling towards the shore with their catches, young women selling fish nearby, and other locals watching the fishing canoes and chatting about the day’s events. Blankson drew our attention back to his historical narrative, suggesting that people used similar canoes for bringing captives out to ships but that this was done under the cover of night in order to quash local resistance and minimize escapes. He described the tragedy of the middle passage. Enslaved Africans were sorted into groups deemed healthy or old and infirm; those who were too sick and those who were found to be pregnant were thrown overboard. Blankson seized the opportunity to draw parallels between the historical treatment of slaves and the economic situation Ghana now finds itself in:

Those who survived and arrived were sold to plantation owners who used them on their farms in the Americas and the Caribbean. During that period there was nothing like a union. So from sunrise to sunset, the masters determined the conditions. And was there a working wage? The proceeds went to building America and Europe. This [pointing to the outdoor surroundings] is now a fishing harbor. We [Ghana and others affected by the slave trade] are highly-indebted poor countries [HIPC]. Those who plundered our human and natural resources—we have to go to them, begging them for aid.

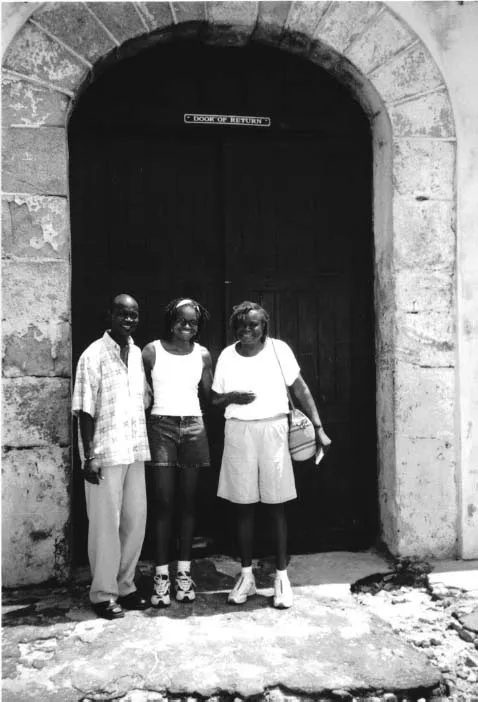

As we turned back towards the castle from the ocean side, Blankson pointed to the top of the door, where a sign labels it as the “Door of Return.” This newly-cast meaning of the passageway was initiated for Ghana’s first recognition of Emancipation Day in 1998 when the remains of two “exslaves” were exhumed from the US and Jamaica and transported back through this door in order to officially mark Ghana as the “Gateway to Africa” for diaspora Africans. With that, Blankson welcomed Amani and Edie home to Africa. They smiled and were happy to hear these words, and I took their picture with Blankson to recall the memory (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Cape Coast Castle’s Door of Return. Blankson, Amani, and Edie at Cape Coast Castle’s Door of Return. Photo by author, 2002.

We walked through the Door of Return, back past the Female Dungeon, and across the courtyard to a small chamber to the right known as the Condemned Cell. Blankson concluded our tour here, where captives who resisted were brought to spend their remaining days. He told us that they stayed in the dark, stuffy chamber without food or water until they died.

After our guided tour, we met some small boys outside the castle. One called Edie “Mama” and told her in a sincere voice, “You look just like my grandmother.” Another had a large, peach-colored shell at the ready complete with the inscription, “To my African sister.” Edie was obviously pleased with these gestures of recognition as a diasporic member of the African family. At the same time, she was well aware of the boys’ opportunism, commenting later that they were “pretty slick.” They asked for pens, spare change, and our addresses. After Edie returned to the States, one of the boys wrote her asking for money and a soccer ball.

CULTURE AS SHARED, CONTESTED, AND IN PROCESS

This excerpt from my fieldwork illustrates the complicated and overlapping disjunctures that characterize the contemporary heritage travel of African Americans to Ghana. When black Americans go to Ghana as pilgrim tourists, are they traveling as, behaving like, or perceived as diaspora Africans, Americans, hyphenated Americans, or foreigners? Homogenizing forces produced by the state, media outlets, cultural nationalists, and capitalism work together to advance the discourse that African-descended folks whose ancestors were forcibly removed from the continent as a direct result of the trans-Atlantic slave trade should now be welcomed back home as diaspora African kin. However, realizing the aim of this message is not so straightforward in practice; individuals and groups may hold fundamentally different assumptions about how slavery should be remembered and about the purpose of reuniting the African family.

Past scholarship has interpreted Ghana’s slavery heritage tourism largely as an economic issue for Ghanaians and an identity issue for diaspora Africans (see Hasty 2002). While my research supports this tendency, additional conclusions may be drawn when looking at the breadth of interactions and power dynamics both historically and contemporarily between Ghanaians and African-descended people in diaspora. Ghanaian heads of state, chiefs, and citizens have made sincere gestures of welcoming African Americans and Afro Caribbeans to Ghana as repeat visitors or “repatriates.” However, these kinds of efforts in reuniting transnational “family members” who have long been separated can simultaneously entail hospitality, ideology, and commercial interest (see Ebron 1999; Routon 2005). African Americans and Jamaicans (among others) have not only participated in pilgrimage tours; some of them have contributed to community-based development, provided schools, and made long-term investments in Ghana—particularly those who have decided to live there permanently. Ordinary Ghanaians are likewise not monolithic in their reception of diasporans. For example in my interviews with Cape Coast residents, some supported the 1998 re-interment of one African American and one Jamaican in Ghana as an important symbolic gesture recognizing these “ex slaves” as kin, while others viewed it as unnecessary and a waste of money. Of course, both the discourses that surround slavery heritage and the relationships between Ghanaians and diasporans can change over time and are always in process. My mixed methods approach combining ethnography with survey research and including the perspectives of everyday Ghanaians, African American visitors and expatriates, and tourism stakeholders sets this work apart from past scholarship on the subject of diasporan homecoming to Ghana (Bruner 1996; Schramm 2010; Finley 2006; Kreamer 2006; Hasty 2002; Holsey 2004). By considering the varied perspectives of multiply situated social actors and analyzing the breadth of engagements people make through heritage travel, I believe we can gain more insight about the cultural dynamics of critical heritage and refine our understanding of how the African diaspora is conceptualized.

In using diaspora Africans or Ghanaians as referents, I do not intend to suggest that these groups are bounded, static, or homogenous cultures; rather, I view them as groups that engage in dynamic systems of meaning (see Foster 1991). I disagree with the proposition that we should abandon the culture concept altogether because it is inherently flawed and necessarily emphasizes how we differ rather than how we are alike (Abu-Lughod 1991). Within any given culture, there are likely to be moments of consensus as well as points of departure. Indeed, if culture were not simultaneously shared and contested, then we would have no grounds for disagreement (Bruner 2005: 249). I believe we can effectively use ethnography to understand how multiply-positioned actors fit into an ever-shifting socio-cultural landscape. Relating this back to Ghana’s pilgrimage tourism, this approach attends to the various ways in which individuals and groups respond to the call to unite as one African family. How are Ghanaians and diaspora Africans finding common ground? What does it mean to be a good family member in this context? What happens when people disagree and do not behave as they are expected to?

CONCEPTUALIZING DIASPORA

This section provides a theoretical overview of diaspora and highlights aspects that are most relevant to the African diaspora within the context of homecoming journeys to Ghana. The concept of diaspora has been defined as an expatriate minority group whose members share some of the following traits:

1) They, or their ancestors, have been dispersed from a specific original “center” to two or more “peripheral,” or foreign, regions; 2) they retain a collective memory, vision, or myth about their original homeland—its physical location, history, and achievements; 3) they believe that they are not—and perhaps cannot be—fully accepted by their host society and therefore feel partly alienated and insulated from it; 4) they regard their ancestral homeland as their true, ideal home and as the place to which they or their descendants would (or should) eventually return—when conditions are appropriate; 5) they believe that they should, collectively, be committed to the maintenance or restoration of their original homeland and to its safety and pr...