![]()

South Asia is assuming increasing importance in world politics in the post-Cold War era. Its significance has grown considerably since 9/11. It is host to one of the world’s most intractable bilateral disputes, Kashmir, between India and Pakistan. It has a substantial Muslim population residing in Pakistan, Bangladesh and India. It has embraced economic liberalization programs leading to stronger links with the rest of the world. Finally, its biggest country, India is the world’s largest democracy, the second-most populous country in the world, a nuclear weapons state with one of the world’s largest military force and the fourth largest economy in the world behind the United States, China and Japan in terms of GDP (purchasing power parity) (Hagerty 2005). By virtue of its size and population, India is the dominant entity in the region and is in a position to influence its smaller neighbors (Ayoob 1989; Hagerty 1991). Given the asymmetry in size and power, its smaller neighbors are understandably apprehensive and suspicious of India’s intentions. As a result of these two factors, India’s relations with its South Asian neighbors (i.e., Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal) have been affected by several disputes and problems.

The South Asian region is important to India and vice-versa. Although India’s relations with the other countries of the South Asian region have been the subject of study for decades, most of these studies have been limited to exploring single-issue areas (e.g., Kashmir dispute) and do not discuss the impact of recent developments in the post-Cold War period. These recent developments include India’s economic rise, the recent democratic transitions in many South Asian countries and greater US engagement in the region following 9/11. This book is an effort to address these issues and examine their role in India’s interactions with its neighbors. This book is not simply a study of India’s past and present foreign policy but also analyzes ongoing political changes and developments in India’s neighborhood.

The first factor/variable (India’s economic rise) outlined above is chosen keeping in mind that all South Asian countries desire to speed up the process of development. India’s economic rise is gradually changing its relationship with its neighbors and there is potential for greater cooperation between the states of the region. Trade liberalization at the regional level would likely contribute to national economic growth and development. Economic development is associated with the emergence of a middle class, which desires political rights. This is crucial to the eventual rise of democracy (Lipset 1959). Trade liberalization fosters democracy and hence there is a causal link between trade openness and democratic governance (López-Córdova and Meissner 2008). To the extent that trade liberalization empowers non-state actors within South Asia, it should have a positive impact on democracy. Trade and commercial links not only lower prices and increase choices for consumers but also promote political rights and civil liberties through the transmission of new ideas, tools and technology. The twin goals of development and democratic consolidation for South Asian countries may therefore be achieved through regional trade liberalization.

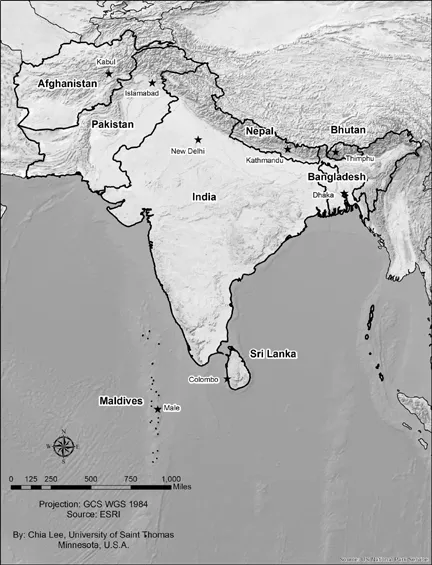

Figure 1.1 Map of South Asia.

In addition, the gradual transition to democracy underway in many South Asian countries is likely to have a positive impact on economic growth and development, hence the choice of the second variable/factor (democratic transition). As Amartya Sen (1999) points out, a democratic political system is crucial to the process of economic development because it helps one understand and fulfill economic needs. Democracies are also unlikely to wage wars against other democracies hence contributing to a more peaceful world. For the purpose of this study, democratic transition/democratization is described as the end of the non-democratic regime, the inauguration of the democratic regime, and then the consolidation of the democratic system (Huntington 1991: 9). However, the process is usually complex and prolonged. In the South Asian region, the process appears underway, but democratic consolidation will take time.

Post 9/11, deeper US engagement with the countries of the region has had an impact on how these countries relate to each other. Some scholars have pointed out that India’s improving relationship with the US has made it more confident and less prone to using coercive methods to address regional concerns (Cartwright 2009; Jain 2010; Kapur and Ganguly 2007; Mitra 2009). There is enhanced cooperation between India and its neighbors on the issue of terrorism, facilitated in some cases by the US. Finally, US presence has been cautiously welcomed by India in light of growing Chinese influence in South Asia. At the same time, US presence in the region can be leveraged by smaller countries to check India’s regional aspirations. The political, economic and diplomatic support provided by the US to some of the smaller countries during the process of democratic transition has proved invaluable. The US is helping to develop the rule of law, independent media, grassroots activism, good governance and transparency in the region (Rocca 2005). According to US policymakers, these are crucial to addressing extremism, security and development in the region. As such, greater involvement of the US in the region since 9/11 is identified as the third variable/factor. The three chosen factors are therefore related to each other.

The other major development affecting the region is the phenomenal rise of China. Even though the rise of China is not one of the variables/factors being considered in this book, China’s rise has implications for South Asia. As rising powers, both India and China strive to influence their neighbors, leading to an overlap in their perceived “spheres of influence.” The strategic rivalry between the two Asian giants is currently being played out in South Asia. This rivalry is inevitable as both compete for resources, foreign investment and markets. Each of the subsequent chapters includes a discussion of China’s involvement in South Asia and its implications on India’s relations with its neighbors. Also included in these chapters are discussions on some of the emerging trends associated with China’s growing involvement with region and whether this involvement helps or hurts the process of regional integration in South Asia. However, these developments deserve a more detailed treatment, which is beyond the scope of this book. As such, the following chapters include a relatively brief examination of the impact of China’s rise on South Asia.

The goal of this book is to answer the three-fold research question: What is the nature of the relationship between India and other South Asian countries? What patterns are observed in the historical interactions between India and its South Asian neighbors? Most importantly, has India’s economic rise, the recent democratic transitions in several countries in the region and greater US engagement in the region following 9/11 affected the nature of the relationship and altered the historical patterns of interactions? The book is intended to:

• Identify the broad tenets of India’s policy towards the other countries of South Asia and the domestic factors that impact India’s policy in the region.

• Outline India’s interactions with the other countries of South Asia.

• Describe recent developments in the smaller South Asian countries and how individual South Asian countries perceive India.

• Explain the multiple issues and challenges that affect India’s relations with other South Asian countries.

• Provide specific examples of the major issues, disputes and conflicts between India and these countries and explore the challenges inherent in promoting peace and cooperation.

• Examine the impact of India’s economic rise, the move towards democratic rule in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Nepal and political transition in Sri Lanka and US engagement in the region since 9/11 on India’s relations with these countries.

Both print and online sources were consulted during the research process. Archival research was an important component of the research methodology. This included primary sources pertaining to India’s bilateral relations with its South Asian neighbors, such as bilateral treaties, official reports, letters and speeches of political leaders. In addition, secondary sources like research reports, commentaries, peer-reviewed journal articles and books pertaining to India’s political relations with its neighbors and information regarding intra-regional trade, economic cooperation were also consulted. Data regarding both the US and EU’s economic relations with South Asia were utilized in studying their respective roles in South Asia. Data was drawn from institutions like the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (Government of India), the Ministry of External Affairs (Government of India), Embassy of India in Nepal, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDS A), India, Federation of Pakistan Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FPCCI), Central Bank of Sri Lanka, Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation (Government of Nepal), Institute for Development Studies (IfDS) Nepal, Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR), United States Department of State, United States Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), International Crisis Group, Freedom House and the World Bank.

In addition, press accounts were examined to determine the nature of India’s historical and present interactions with its neighbors and with other major powers. This also provided an insight into discussions between India’s elites regarding the need for change in the country’s international orientation in the context of the transition of the international system following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Peer-reviewed journal articles, books, research reports, etc., were also consulted. These accounts help examine the three developments outlined earlier and the role of extra-regional actors in South Asia. Information from archival research and press accounts, among other things was used to support the basic premise of this book.

This chapter will provide an overview of South Asia. It will open with a discussion on what constitutes the South Asian region. Next, it will present a brief historical overview of the region from the pre-Indus Valley civilization period to European colonialism and independence. An understanding of South Asia’s geography and political and social history is necessary to provide the context for some of the disputes/issues that affect India’s relations with other South Asian countries. Finally, it will briefly introduce the three recent developments outlined earlier and their implications for South Asia. It will end with an overview of the subsequent chapters.

Geography

South Asia is a land of extraordinary diversity. Most standard definitions include the following countries: India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan and Maldives. Sometimes it is also referred to as the “Indian subcontinent” or simply the “sub-continent” because it is a self-contained landmass within the larger Asian continent. The South Asian region is bound by the mighty Himalayas to the north, the Bay of Bengal to the east, the Indian Ocean to the south and the Arabian Sea to the west. These natural borders set it apart from the rest of Asia not just in terms of geography but also in terms of identity. Within these natural borders, the South Asian region displays a wide range of climatic conditions and physiography.

The South Asian region can be broadly divided into five major physiographic divisions: The Greater Himalayas, Great Plains, Great Indian Desert, Great Peninsular region and Coastal Plains.1 Since agriculture is the mainstay of the economies of South Asia, this section will focus primarily on the Greater Himalayas and the Great Plains due to their implications for agriculture in the region.

The Greater Himalayas are a series of parallel mountain ranges, whose general orientation is from northwest to southeast, stretching as an arc for nearly 1,500 miles across the northern edge of Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal and Bhutan. The Greater Himalayas include the Hindu Kush mountain ranges (Afghanistan and Pakistan) and the Karakoram mountain ranges (Pakistan and India). The Greater Himalayas are dissected by rivers, glaciers, gorges and valleys. They are considered to be one of the youngest and highest mountain ranges on Earth. It is home to the three tallest peaks in the world, Mt. Everest (Nepal), Mt. K2 (Pakistan) and Mt. Kanchenjunga (India). The Greater Himalayas also include the world’s second longest glacier (Siachen) and third longest glacier (Biafo) outside the polar regions. Most of the Himalayan peaks remain snow-covered throughout the year. These mountain ranges are critical to the region in more ways than one. They act as a barrier against the frigid winds from Central Asia and Tibet, keeping the South Asian region mildly cool during winters. The Himalayas also play an important role in bringing monsoon winds (seasonal winds) from the Indian Ocean during the summer, thereby providing the region with life-sustaining rainfall. Without this rainfall, agriculture in the region would collapse. Finally, the Himalayas have often acted as a natural barrier preventing the easy movement of foreign invaders into the region (Dutt 2010).

The Great Plains includes the three major river systems of South Asia: the Indus, the Ganges and the Brahmaputra, all of which originate in the Himalayas. These river systems form alluvial plains, stretching across the north-central region of the sub-continent. The Indus river flows through Pakistan into the Arabian Sea, whereas the Ganges travels east across north India and merges with the Brahmaputra in Bangladesh before ending in the Bay of Bengal. The Brahmaputra River flows east from Tibet into north-eastern India and then south into Bangladesh. The Indus is the lifeline of Pakistan, the Ganges is the lifeline of India and the Brahmaputra delta system is the lifeline of Bangladesh. The plains area in Nepal primarily includes the Terai, a densely populated region south of the Himalayas. Due to these river systems, the Great Plains area is naturally irrigated and is the breadbasket of the region. The main crops grown here include rice, wheat, maize, sugarcane, cotton and jute. This region is also one of the most densely populated in the world. The Ganges is the most sacred river for Hindus and bathing in the river is believed to wash away one’s sins. Along the banks of the river lie several Hindu pilgrimage sites. Some of the tributaries of the three rivers – Yamuna, Ravi, Beas, Satluj, Chenab, Teesta, Kosi and Meghna – are major rivers of the region.

The climate of the South Asian region is as diverse as its geography. Most of the countries in the region have a tropical and sub-tropical climate, except Afghanistan, northern Nepal and Bhutan. The region has four major seasons: Winter (January–February), Summer (March–May), Monsoon/Rainy season (June–September) and post-Monsoon period (October–December). The Himalayas keep most of the South Asian region relatively warm in winter, while the monsoon rains make the region relatively cool in summer. However, average temperatures can range from 115°F in the Thar Desert region in summer to −50°F in some parts of the Himalayan region in winter. Temperatures in the plains can fall below freezing in winter and go up to 110°F in summer. Temperatures in the Peninsular and Coastal regions display less variation. The climate of South Asia is affected by factors such as location, altitude, distance from sea and geographical features, such as mountains.

The monsoon winds which bring rain to much of the region are the most important climatic feature (Pichamuthu 1967). As temperatures rapidly increase in May over the Great Plains and Peninsular regions, the low pressure conditions intensify. This in turn attracts the trade winds of the Southern Hemisphere from the Indian Ocean. Upon crossing the equator, they follow a southwesterly direction and are therefore called south-west monsoons. These winds divide into two branches: the Arabian Sea branch and the Bay of Bengal branch as they approach the South Asian landmass. These winds provide rain to almost all countries of South Asia. The monsoon winds retreat from South Asia during October–November (post-Monsoon period) in a north-easterly direction, but not before shedding rain over much of eastern India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. The monsoon itself is fickle and unpredictable. Farmers depend on the monsoon. A delayed or weak monsoon leads to drought-like conditions across the region impacting economic growth and development. A powerful monsoon can lead to flooding causing untold miseries for not just farmers but others as well.

History

Since India is the largest entity in South Asia, the history of the region mirrors India’s history. Hence, this discussion on South Asia’s history is primarily about India’s history. South Asia is home to one of the world’s earliest Neolithic cultures: Mehrgarh (Avari 2007). It began in around 7000 BCE and lasted until around 3000 BCE. This culture flourished in the modern day Baluchistan province of Pakistan and was also one of the earliest known centers of agriculture in South Asia. The Indus Valley Civilization, a Bronze Age civilization, followed the Mehrgarh culture. It flourished during the period between 2500−1500 BCE. This civilization is also referred to as the Harappan civilization, after the ancient site of Harappa located in the Indus river valley region. Most linguists identify the current Dravidian culture and language of the peoples of South India with the ancient Harappan civilization. This is one of the world’s earliest urban civilizations and was discovered in 1920 CE. The Indus Valley Civilization is now believed to ...