- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Islam and Pakistan's Political Culture

About this book

This book explores the ideological rivalry which is fuelling political instability in Muslim polities, discussing this in relation to Pakistan. It argues that the principal dilemma for Muslim polities is how to reconcile modernity and tradition. It discusses existing scholarship on the subject, outlines how Muslim political thought and political culture have developed over time, and then relates all this to Pakistan's political evolution, present political culture, and growing instability. The book concludes that traditionalist and secularist approaches to reconciling modernity and tradition have not succeeded, and have in fact led to instability, and that a revivalist approach is more likely to be successful.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Islam and Pakistan's Political Culture by Farhan Mujahid Chak in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teologia e religione & Teologia islamica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

The symbol of Islam is not the Wheel of Dharma, the Shield of David or the Crucifix. It is, undoubtedly, the cube of the Kaa’ba. That immovable, stable and enduring symbol of permanence represents the absolute character of Islam. If there ever was a symbol that so completely represents the spirit of Islam it is the Kaa’ba: perpetual certainty, or ‘permanence,’ constantly surrounded by the ‘impermanence’ of orbiting believers who represent both dynamism and flux. This, after all, sends a powerful message: life is full of change, yet we often live for those things that don’t change. Clearly, ‘meaning’ in our lives exists as a consequence of permanence – and this is precisely what comes under question in the modern world.1 Contrarily, this ‘permanence’ remains the mainspring of an Islamic ethos.

‘Once the spirit of Islamic revelation had brought into being, out of the heritage of previous civilizations and through its own genius, the civilization that may be called distinctly “Islamic”, the main interest turned away from change and adaptation’.2 Henceforth, its corresponding epistemology came to embody a ‘permanence’ premised on the ‘certainty’ of the principles from which they issued forth. This ‘permanence’, in fact, is far too often mistaken as inertia in Muslim societies. Yet, more succinctly, it reflects the unique bal-ance that Islamic civilization instils between enduring principles and changing circumstances.

Today, many Muslim polities attempt to intelligently reconcile the twin forces of ‘permanence’ – thabit – and ‘change’ – mutaghayir. Relatedly, this reconciliation includes managing modernity and tradition. Though nowhere is the problematic nature of reconciliation better exhibited than when deconstructing political culture in Muslim polities. It is here that the antecedents of political instability may be understood. Therefore, in recognition of that chronic, internal civilizational tussle between permanence and change, this book analyzes political culture to understand the roots of its ideological and consequential political instability. However, conclusions drawn and insights gained are relevant across Muslim majority countries.

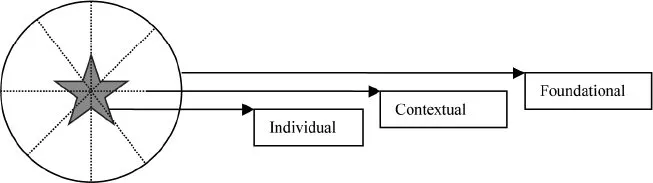

To begin with, this book thoroughly reviews the literature on political culture and locates, therein, constant references to the ‘core’, ‘existing meaning’, ‘enduring cultural component’ or ‘stock of knowledge’ in a given polity. Then those unexplained terms are used to describe the essence of political culture, alluding to its intrinsic values. Yet that allusion is vague, since what the ‘core’ exactly consists of, amounts to or how it may alter, is left largely undefined. Here we are provided a concept that is meant to do the explaining, which itself requires an explanation. Therefore, this book proceeds to define that ‘core’, with regard to Muslim polities, and labels it as the ‘foundational’ aspect of Islamic political culture. This, effectively, represents its deeply cherished political ideals, yet is only the first sphere of inquiry essential to understand the totality of political culture in Muslim polities. Specifically, understanding that totality involves grasping the complex interplay between the ‘core’ political ideals that are symbolic of permanence, the changing context in which they are evident, as in Pakistan, and the approach political leadership chooses to interact with both. In other words, understanding Islamic political culture involves three spheres of inquiry: ‘foundational’ (what endures or should be), ‘contextual’ (what is) and ‘individual’ (the agent for movement), illustrated in Figure 1.1 below:

Figure 1.1 Graphic representation of the requisites for political stability in Muslim polities, which requires a balance between the three spheres of inquiry.

Strictly speaking, the solid outer circle is the ‘foundational’ sphere of inquiry, which includes those patterns of behaviour, norms, and cultural assumptions collectively representing the core ideological and political platform of Islam – the ‘ideals’. In this study, it includes the Qur’anic theory of knowledge, the political ideals extracted from both the Qur’an and Prophetic sayings with, lastly, the Rashidun era. Essentially, these four variables enable us to extract deep-rooted political principles and set them forth as an ‘ideal type’. These ‘ideals’, then, are manifest not only in Muslim society in Pakistan, but throughout the entire Muslim world, albeit to varying degrees. Straightforward to this analytical approach is the assumption that the ideals incorporated at the ‘foundational’ sphere of inquiry are of significant consequence, having a pivotal impact on the organization and direction of political life. Second, the criss-crossing and porous lines inside the circle, symbolic of impermanence, represent the ‘contextual’ sphere of inquiry. This pertains to the way the ‘foundational’ finds expression, depth and meaning, for instance in Pakistan. And is representative of the spread of ‘foundational’ ideals of Islam to regions beyond Hejaz and its consequent interfacing with divergent sociocultural realities. However, to limit the scope of our analysis, the time frame for our study begins during the early twentieth century Pakistan movement, moves on to include its fractious constitutional development and ends with civil-military analysis. Third, the star in the centre, another aspect of impermanence, represents the individual that responds to both forces and, similarly, influences them in application or form.

Collectively, these three spheres of inquiry comprise the composite Islamic political culture and coexist simultaneously. The ‘core’ values, the manner in which they find expression in space-time and the agent for movement directly impact its manifestation. Therefore, any analysis focusing singularly on one sphere of inquiry would be deficient in revealing its totality. Consequently, this trilateral approach is intended to shun simplistic analyses, and is calculated to offer a careful framework – without dissociating the inquiry from its sociological context.3 Furthermore, this approach disqualifies both the portrayal of a monolithic Islamic political culture across spatial and temporal bounds, to a degree defying empirical realities, and those who insist of there being no commonality across Islamdom.

This triangular relationship lies at the heart of understanding Islamic political culture and produces three variant political cultures – namely, ‘traditionalist’, ‘secularist’ and ‘revivalist’. More clearly, the differing manner in which ‘individual’ political leaders in their ‘context’, such as Pakistan, choose to interact with the ‘foundational’ produces them. This interaction, however, is, largely, antagonistic, not solely as a result of their diverse understandings, but also by competing for control of the centres of power. As a result, the conflict between these variant political cultures contributes towards ideological and political instability. Yet the ‘revivalist’ political-culture type manages this rivalry by both a restraining influence and cohesiveness that resolves issues of instability insomuch as it hinders development, progress and direction.

Here, this study proceeds to take into consideration two pioneering figures of the Pakistan movement, Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Muhammad Iqbal. It closely examines and characterizes them as ‘revivalists’ who expressed a vision that resonated or connected with their people. Resultantly, they succeeded in fostering unity, amidst diversity, towards a common directive. Not only did they balance the ‘core’ values of their society with their present-day realities, but understood power as meaningless without popular support. Accordingly, their narrative was rooted in the sensibilities of their context, based on established tradition, ongoing through the process of enculturation.

Furthermore, both Jinnah and Iqbal may be portrayed as ‘revivalists’, or harbingers of a new ‘asabiyya’, by the manner in which they responded to the challenges of their time.4 That included a clear vision for the future rooted in an appreciation of their cultural and religious past, though not necessarily bound by it. Granted, these leaders were competing and contesting dissimilar meanings held by ‘traditionalists’ – who were unable or unwilling to synthesise Islamic ideals with the idea of the nation-state, or ‘secularists’ who did not recognize the importance of Islam in their political narrative. Admittedly, the depiction of both Jinnah and Iqbal as ‘revivalists’ may be disputed. Indeed, today in Pakistan it is a hotly contested issue. Yet what is undeniable is that they both chose to not ‘disconnect’ in idea, word or deed, from either the historiography – which ‘secularists’ often ignore – or the contemporariness – which ‘traditionalists’ often ignore – of their society. Fittingly, they prevented delegitimizing themselves in the eyes of their people and succeeded in galvanizing an ethnically diverse mass into a cohesive unit. This, too, irrespective of opposition from the traditionalists and secularists, both of whom opposed an independent homeland for Muslims. Taking that into account, what has popularly been referred to as the ‘Arab Spring’ is simply, another manifestation of ‘revivalists’ securing the support of the majority of people in Muslim polities and seizing their rightful place at the helm of socio-economic, cultural and political affairs. This, too, in spite of resentment and resistance by secularists and traditionalists, who, disregarding lip service, tend to be wary of democratization.

In total, this book critiques the concept of political culture and offers an alternative methodology to explain Islamic political culture. As such, it begins by analysing the early foundational mores of an Islamic polity based on four variables: its epistemic tradition, the Qur’an, Prophetic sayings and Rashidun era. Together, this leads to the analytical formation of the ‘foundational’ sphere of inquiry, the first explanatory variable. Then it places that in the context of Pakistan and assesses how individuals interact with it. By doing so, this study reveals the development of competing political cultures, with their own understandings and trajectories, whose interaction broadens ideological and political instability.

Concerning the archetype of the early foundational mores, this book does not merely propose to reiterate the early Islamic era as the ideal and the eras following as mere efforts to reach or catch up. Instead, there is a reinvention of that ‘ideal’ relevant to the context in which it arises, which disqualifies any contradiction towards the foundational insomuch as it seeks to garner legitimacy. Certainly, for one to ‘catch up’ to an ideal it must, from the onset, be accepted as the benchmark to achieve. For that reason, this study insists ‘ideals’ exist as a consequence of principles espoused by its epistemic tradition and enculturation.5 The challenge, then, is to create it anew, acknowledging that renewal is not linear, in that there needs to be a return to a specific ideal thought to exist in the past. Utopia is not, necessarily, mimicking of bygone days, or to put it plainly ‘going back in time to an idealized past’. Nor does it require viewing the world as the source of ills and conflicts, and not humans, and by doing so making human life expendable.6 Yet the ‘ideal’ does exist in any society with regard to its ethical, socio-economic and political direction. Thus, ‘foundational’ mores cannot be ignored, nor can present conditions. In essence, it is this creative articulation of enduring principles and its present-day application that the ‘revivalist’ in Muslim polities wishes to realize, the ‘traditionalists’ wish to resist and the ‘secularists’ wish to deny.

Subsequent efforts, throughout Muslim history, to create such ‘utopias’ were the responsibility of ‘revivalists’ in which they, per se, aim to actualize its substance, or maqasid, rather than merely its form.7 In our analysis, the ‘revivalists’ in Muslim polities do so by responding to challenges with a solution that steers away from both the ‘traditionalist’ and ‘secularist.’ Both largely understand Islam as a monolithic and unchanging dispensation, albeit for their own reasons.8 It is undeniable that early schisms existed in Islam, as they persist today. Nevertheless, the ‘revivalist’ aims at recognizing the strength and wisdom of diversity – a diversity that includes different ideas and colours, unusual beliefs and devotion, dissimilar languages and race. Truly, appreciating diversity is recognizing all those differences, still maintaining convergence of purpose, even while insisting on differing methods and then, lastly, trusting that ‘God knows best’.

It may be noted that this high classicalism is similar to other religio-political ideals, as well, if one looks at Jewish history or the classical Hindu age in India, now being idealised amongst the Hindutva proponents. Often such ‘utopianism’ may be, as John Gray says, based on millenarianism, which is not unique to Abrah...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- Maps

- Chronology of major political events

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Deconstructing political culture

- Part 1: Foundational sphere of inquiry

- Part 2: Contextual and individual spheres of inquiry

- Index