![]()

Part I

Governance under hybrid regimes

The case of Hong Kong

![]()

1 Governance crisis in post-1997 Hong Kong

In search of a new theoretical explanation

The politics of hybrid regimes: the case of Hong Kong

The growing scholarly attention on hybrid regimes

In recent years there have been increasing academic discussions and debates in the field of comparative political studies about “hybrid regimes”, which by definition combine both democratic and authoritarian elements (e.g. Diamond, 2002; Levitsky & Way, 2002; Schedler, 2002). This new wave of scholarly attention is attributable to the fact that the “third wave of democratization” as advocated by the renowned American political scientist Samuel Huntington in the 1990s has already come to a halt in recent years. Instead, there is unprecedented growth in the number of hybrid regimes in the world and experts predicted that these intermediate regimes will likely remain in the “political grey zone” between full democracies and outright authoritarianism over a long period of time (Diamond, 2002).

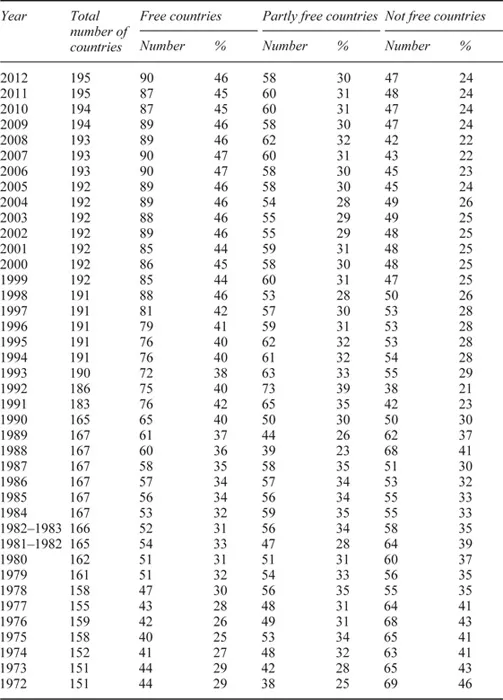

According to the Freedom House’s “Freedom of the World 2013”, which provided comparative assessment of global political rights and civil liberties,1 58 out of the 195 countries around the globe could be considered as “partly free” hybrid regimes in 2012, representing 30 per cent of the world’s countries and covering about 23 per cent of the world population (Table 1.1). Countries falling into this category have been on an increasing trend in recent decades and now include Albania, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Georgia, Libya, Malaysia, Mexico, Paraguay, Singapore, Turkey, Ukraine and Venezuela. According to the studies of the Freedom House, these “partly free” hybrid regimes are usually characterized by limited respect for political rights and civil liberties, under which an incumbent dominates the political landscape while tolerating a certain degree of pluralism (Freedom House, 2013).

As a consequence of the growing importance of these hybrid regimes in the contemporary political map, it was not surprising that there has been a great deal of comparative political studies in recent years which aimed at accounting for the nature and characteristics of hybrid regimes (e.g. Brownlee, 2007; Case, 2005, 2008; Levitsky & Way, 2010; Slater, 2010).

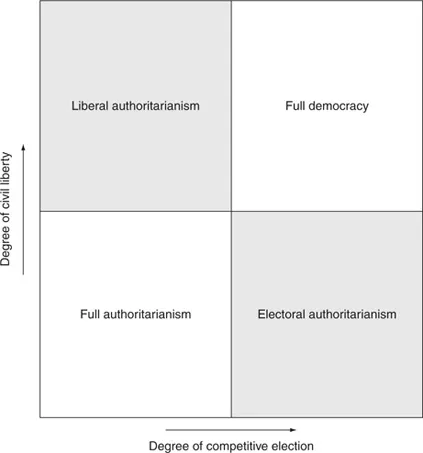

Clearly, the increasing scholarly attention on the notion of hybrid regimes is built upon the understanding that competitive election is the necessary condition – but not the sufficient condition – for democracy, and thus political regimes should not be classified as democracies simply because they hold regular multiparty elections on the basis of universal suffrage (Diamond, 2002; Schedler, 2002). For scholars of hybrid regimes, modern democracies should not only be defined as a system of holding regular multiparty elections, but should also encompass the relaxation of controls on political activities and the recognition of basic civil rights. Following renowned political scientist Robert Dahl’s classical theories of polyarchies, comparative theorists considered competitive elections and civil liberties as the two basic dimensions of modern democratic systems, and only when both of these two dimensions of democracy are present can such a political regime be categorized as “full democracy”; a political regime should be classified as “full authoritarianism” when neither dimension exists (Case, 2008). Between these two poles of full democracy and full authoritarianism, conceptually there are two typical forms of hybrid regimes, namely “liberal authoritarianism” (also known as “semi-authoritarianism”) and “electoral authoritarianism” (also known as “semi-democracy” or “competitive authoritarianism”).

Table 1.1 Number of “partly free” hybrid regimes (1972–2012)

Source: Freedom House, 2013.

Under liberal authoritarianism, while civil liberties are to a large extent respected and the activities of interest groups and opposition parties are generally recognized, popular election for the national chief executive is absent and opposition forces’ access to government power are basically denied. In contrast, under electoral authoritarianism there are regular multiparty elections for the national chief executive operated on the basis of universal suffrage, but civil liberties are largely suppressed by the government in order to prevent the opposition forces from mobilizing against the authoritarian incumbents and endangering its continued hegemony (Case, 1996, 2008; O’Donnell & Schmitter, 1986). This scheme of classification results in the fourfold typology shown in Figure 1.1, which broadly captures the four ideal types of political regimes that can be found in contemporary societies.

For much of the existing studies of democratization, hybrid regimes were described by political scientists as unstable and transitional regimes (Levitsky & Way, 2010, p. 1). By combining both democratic and authoritarian elements within a single political regime, hybrid regimes, no matter whether they are liberal authoritarianism or electoral authoritarianism, were said to be experiencing endless political conflicts between the incumbent and the opposition. In the eyes of many political scientists, hybrid regimes are an unstable form of government and are more vulnerable to different kinds of governance problems and political instability than full democracies and full authoritarianism (Goldstone et al., 2005).

For liberal authoritarian regimes, the trend of political liberalization will often stimulate people’s desire for a greater pace of democratization and also provide important fertile ground for opposition parties and civil society organizations to mobilize their supporters against the authoritarian incumbents. Motivated by civil liberties to participate in politics but denied real access to government power through democratic elections, opposition forces under liberal authoritarian regimes may eventually seek political reforms through anti-establishment behaviours. Intense political pressures and tensions are therefore continuously placed upon the political system, paving the way for pushing towards a full democratic transition (Case, 2008; Huntington, 1991).

Figure 1.1 A fourfold typology of political regimes

Similarly, under electoral authoritarian regimes, the incumbents’ attempts to maintain their political powers through manipulation of elections and suppression of civil society’s activities will usually stir up confrontations with opposition forces. In this connection, authoritarian rulers are always situated in a “nebulous zone of structural ambivalence”, swinging from imposing tighter control on elections and civil society but at the cost of intensifying domestic conflicts and inviting international isolation, to tolerating the challenges of opposition parties but at the expense of regime uncertainties. Comparative theorists have observed that these political dilemmas and persistent rivalries have brought about political crisis in many hybrid regimes like Mexico in 1988, Russia in 1993 and Albania in 1997 (Levitsky & Way, 2002; Schedler, 2002).

Hong Kong as a hybrid regime and its governance crisis after 1997

In the context of comparative political studies, Hong Kong is an interesting case of hybrid regime. Since the colonial era, the British colonial government had put in place a liberal authoritarian regime in the city-state: while political powers were concentrated in the hands of the colonial administration headed by the Governor and the people of Hong Kong were denied the rights to choose their own government though democratic elections, a high level of civil liberties, independence of judicial courts and rule of law that were on a par with that of many well-developed Western democratic regimes had been in place for many decades. In this regard, the establishment of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) on 1 July 1997 did not change Hong Kong’s liberal authoritarian regime, because various civil liberties have been generally guaranteed under the Basic Law. On the other hand, while the process of democratization had already been started in the mid 1980s, Hong Kong is still far away from developed into a full-fledged democracy due to its limited electoral franchise. Nowadays, half of the seats in the Legislative Council are selected by popular elections, and the Chief Executive, who replaced the colonial Governor as the executive head after 1997, remains handpicked by an election committee controlled by the Beijing government and could not be held accountable to the legislature or people of Hong Kong (Lau & Kuan, 2002).

By maintaining the high degree of civil liberties and incorporating some limited elements of democratic elections, Hong Kong’s experience is quite unusual in comparative political studies and could be considered as a particular type of hybrid regime: the post-1997 Hong Kong is fundamentally a liberal authoritarian regime featuring some electoral authoritarian elements2 (Case, 2008). The academics questions here are whether Hong Kong, as a particular type of hybrid regime, experiences the same inherent risk of instability and political conflicts commonly found in other hybrid regimes. If Hong Kong is considered to experience crisis of governance, are these problems closely connected to the territory’s hybrid regime or contributed by other factors? Was Hong Kong’s experience unique in any sense?

Comparative political studies indicate that hybrid regimes usually encounter political confrontations between the authoritarian governments and the opposition forces, and it is not uncommon for them to experience serious political instabilities and conflicts like revolutionary wars, adverse regime changes, collapse of state power, ethnic conflicts and genocides (Goldstone et al., 2005). Obviously, unlike other hybrid regimes, Hong Kong so far has not experienced this kind of serious political turmoil or violent conflict. In fact, since the handover of sovereignty the post-colonial state has managed the day-to-day administration of the society quite effectively; thanks to the highly efficient and clean civil service, independent judiciary and sound rule of law system, Hong Kong has been successful in preserving its political stability, maintaining efficient delivery of public services and ensuring law and order.3 Most importantly, given Hong Kong’s status as an autonomous region under Chinese sovereignty, Beijing performed as an important force for blocking democratic change and preserving overall political stability in the territory, making its hybrid regime more persistent than other similar polities (Case, 2008). Although Hong Kong’s overall political situations are clearly much more stable than many other hybrid regimes, it does not mean that the territory is free from political confrontations and governance problems. Since the handover of sovereignty in 1997, “governance crisis” has become the most popular term used by local politicians, commentators and academics to describe the political situation in post-colonial Hong Kong. From time to time, the post-1997 governance crisis has been described by different scholars as “institutional incompatibility” (Cheung, 2005a, 2005b), “hollowing-out of executive power” (Cheung, 2007), “disarticulation of the political system” (Scott, 2000), “political decay” (Lo, 2001) or “institutional incongruity” (Lee, 1999). In the eyes of many local political scientists and researchers, Hong Kong has been trapped in a governance crisis after 1997 and there seems to be no clear prospect of improvement in the foreseeable future.

But what are the nature and characteristics of the so-called “governance crisis” in the post-1997 Hong Kong? Conceptually, there is no universally accepted definition of “governance crisis” in political science literature and its manifestation differs greatly across societies; thus the substance and seriousness of the governance crisis in Hong Kong can only be understood in the specific political contexts of the territory (Lau, 1994). From this perspective, when compared with its colonial predecessor, the post-colonial state has been facing an unprecedented governance crisis since 1997. Such a governance crisis has been expressed on three major fronts. First, the post-colonial state is facing growing challenges in re-embedding itself with major socio-economic actors and it is struggling to forge societal acceptance for delivering policy changes. Second, the post-colonial state’s relative autonomy is fac...