eBook - ePub

Class and Space (RLE Social Theory)

The Making of Urban Society

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Class and Space (RLE Social Theory)

The Making of Urban Society

About this book

This book is abut the place of space in the study of class formation. It consists of a set of papers that fix on different aspects of the human geography of class formation at different points in the history of Britain and the United States over the course of the last 200 years. The book shows that the geography of class formation is a valuable and cross-disciplinary tool in the study of modern societies, integrating the work of human geographers with that of social historians, sociologists, social anthropologists and other social scientists in an enterprise which emphasises the essential unity of social science.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Class and Space (RLE Social Theory) by Nigel Thrift, Peter Williams, Nigel Thrift,Peter Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

• 1 •

The geography of class formation • NIGEL THRIFT AND PETER WILLIAMS

Introduction

This chapter provides an introduction to the subject of Class and Space. Its purpose is to briefly survey the literature on class and the geography of class in capitalist societies. The chapter is based on the presumption that the analysis of classes should start with the social relations of production but, as will become clear, the analysis cannot end there. Other perspectives on class are valuable too. Quite clearly, the insights provided by, for example, the Weberian approach are important for the analysis of classes in modern capitalist societies. As Abercrombie and Urry (1983, p. 91) put it concerning the middle classes:

As ‘Weberians’ have become worried about the Boundary Problem, and ‘Marxists’ have recognised the importance of middle classes, the theoretical waters were bound to become muddy. In these circumstances it is more profitable to worry less about the way in which one discourse is privileged over another and more about the manner in which an adequate theory of the middle class can be constructed.

This chapter is split into three main parts. The first part provides a general introduction to the theory of class, concentrating on the chief determinants of class formation. The second part is intended to establish the role of geography in the study of classes. In the third and final part of the chapter we briefly review the contributions to the volume placing them in the context of our discussions here.

1 A space for class

The first problem in any discussion of class is how class is to be defined and it is therefore with this problem that the discussion must begin.

Defining class

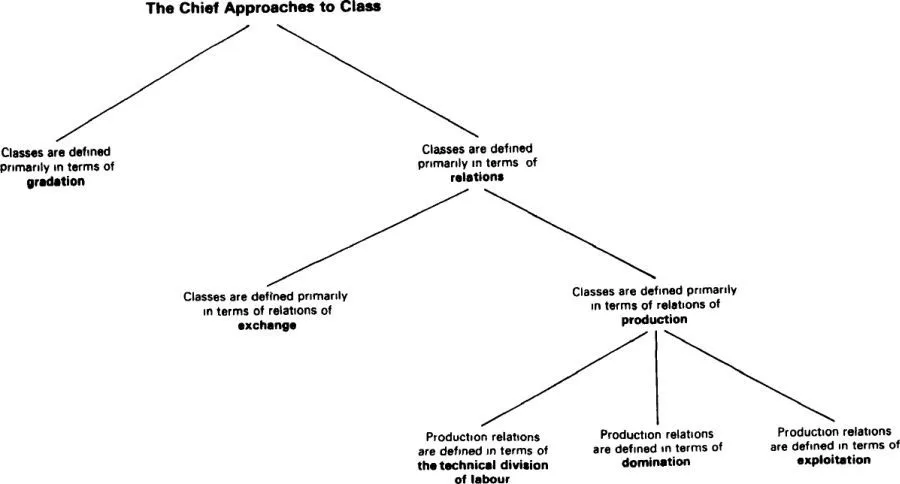

Figure 1.1 shows some of the chief approaches to the definition of class within capitalism. Wright (1979b) has analysed these approaches in terms of three sets of oppositions. First, a distinction can be drawn between gradational and relational theories of class (Ossowski, 1963). Gradational approaches are usually based on the notion that classes differ by quantitative degrees on attributes like status or income. It is this gradational approach (usually based on official gradational classifications) which underlies much of the little work done in human geography which includes class as a variable. But such an approach is without any real explanatory power. Explanation requires a conception of class in relational rather than relative terms, that is as a set of social relations between classes which define their nature. Of course, relationally defined classes can have gradational properties – capitalists are rich and workers are poor. But it is not these properties as such which define classes. Rather, it is the other way round. The social relations between classes explain at least the most essential features of their gradations (Wright, 1985).

Figure 1.1 The chief approaches to class

Source: Wright, 1979b.

Given a relational conception of class, a second distinction can be drawn according to whether class is seen as primarily determined by social relations of exchange (‘the market’) or social relations of production. The conception of class based on market relations is usually attributed to Max Weber, although this attribution is all too often allowed to degenerate into a crude caricature of Weber’s ideas (e.g. Wright, 1979b). In fact, in Weber’s scheme of things class consists of two dimensions: market interests, which always exist independently of men and women and influence their life chances, and status affiliations. The two dimensions represent the two different strategies that are open to a class and their emphasis changes through history (Giddens, 1973). This Weberian conception of class has been widely used in political theory (e.g. Parkin, 1972) and urban studies (e.g. Rex and Moore, 1967; Saunders, 1979, 1981). The conception of class based on relations of production is usually associated with the name of Marx. However, there are at least three ways in which class can be so defined and still remain consistent with a definition based on social relations of production and only one of these is, in fact, Marxist.

These three definitions provide the final set of distinctions that can be drawn. First of all, class can be defined according to occupation. In this case the theoretical backdrop is usually provided by a variant on the theme of the increasing technical division of labour (e.g. Bell, 1973; Berger and Piore, 1980). Second, class can be defined according to possession of, or exclusion from, the authority to be able to issue commands to others (e.g. Dahrendorf, 1959), that is as a set of relations of domination. Lastly, class can be defined as the contradictory relation between capital and labour which allows surplus value to be appropriated, that is as a set of relations of exploitation. This is the Marxist view that there is a causal relationship between the affluence of one class and the poverty of another.

Of course, all classifications of approaches to class have their problems and Wright’s is no exception. First, a number of the relational views of class incorporate to a greater or lesser degree Marx’s view on class. Some of them were first put forward as reactions to, explicit critiques of, or simple additions to Marx. Thus Marx is often criticised for either not realising that there were other dimensions to class than production, or, because of his position in history, not having access to later developments which show that his theory of class needed adjustments or additions. Second, many authors fit uncomfortably into any classification. Giddens’s (1973) theory of class structuration, for example, incorporates elements of both Marx and Weber’s concepts of class and, in consequence, is far less easy to assign to a market or a production relation approach than Wright assumes (see Giddens, 1979b).

This chapter takes as its starting point (and only the starting point) the Marxist definition of class; that is class is based in social relations of production that are exploitative. Quite clearly, this definition means that certain social groups like women or religious or ethnic groups are not classes. This is emphatically not to downgrade these social groups. Indeed, one of the major points of modern Marxist analysis has been to take proper account of their importance. It is certainly not to suggest that these such social groupings are excluded from membership of classes. That would be absurd. Similarly it is not to suggest that these social groupings have no effects on the formation of classes. They clearly do have important effects. Wright (1985, pp. 129–30) sums up the Marxist position particularly well with regard to women:

Class is not equivalent to ‘oppression’, and so long as different categories of women own different types and amounts of productive assets, and by virtue of that ownership enter into different positions within the social relations of production, then women qua women cannot be considered a ‘class’. A capitalist woman is a capitalist and exploits workers (and others), both men and women, by virtue of being a capitalist. She may also be oppressed as a woman in various ways and this may generate certain woman non-class interests with the women she exploits, but it does not place her and her female employees in a common gender ‘class’.

Doing class analysis: some basic concepts

It has become something of a truism that Marx never developed any systematic account of class: the text of the final chapter of Capital, Volume 3 entitled ‘Classes’ breaks off after just one page. This has been the opportunity for a whole host of (often dogmatic) recoveries of what Marx really meant about class to be developed by subsequent writers in the Marxist tradition (Giddens, 1979b). In this chapter, however, our concern is not with any kind of historical salvage operation but rather with the extension of some of the basic Marxist concepts of class.

Marx’s account of class under capitalism is constructed at two levels of abstraction. At the highest level of abstraction Marx provides an analysis of the contradictory, exploitative and antagonistic relation between capital and wage labour that sustains capital and labour as classes and guarantees the presence of some degree of class conflict. At the lowest level of abstraction Marx provides a series of concrete historical analyses characterised by a large cast of classes, class functions and other social groupings. For example, ‘in the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte he refers to at least the following actors in social conflicts: bourgeoisie, proletariat, large land owners, aristocracy of finance, peasants, petty bourgeoisie, the middle class, the lumpen proletariat, industrial bourgeoisie, high dignitaries’ (Wright, 1985, p. 7).

The overriding problem still is how to get from the most abstract two class account of the relations of production that Marx provides in the model world of Capital to the multiplicity of classes in constant formation and deformation that characterise Marx’s accounts of real societies. There is no easy solution, of course. Currently five major concepts are fairly consistently utilised in a class analysis, namely class structure, the formation of classes, class conflict, class capacity and class consciousness. These concepts are likely to become more or less important in class analysis depending upon the spatial and temporal scales that are chosen. Class analysis at the grandest of these scales tends to put the emphasis upon long-term changes in the relations of production over large areas of territory. Such an approach can reveal fundamental shifts in class structure arising out of the changing trajectory of capitalist development. Alternatively, comparative studies of the class structures of different countries can be revealing. Class analysis can also be carried out at more restricted temporal and spatial scales, for example in a region over the course of forty or fifty years. In this case, much more attention must be paid to the exact mix of institutions that both generates and is generated by shifts in class structure. At this level of resolution, the formation of classes, the detailed to and fro of class conflict and the strength of class capacity all become more apparent. Finally, class analysis can be conducted at smaller spatial and temporal scales, often within a specific community. Here close attention tends to be paid to the exact class practices that institutions generate and the way that these practices mesh to create subjectivity and the particular actions needed to produce, sustain and question daily life. Hence the definition of class consciousness becomes particularly important. Of course, each of these five concepts can be deployed at any spatial and temporal scale, and they often are. The argument here is only that the nature of the scale chosen at which to practice class analysis is more likely to throw particular concepts into relief than others.

The way in which these five concepts are thought of is important and this chapter therefore continues by giving a modern interpretation of these concepts. Clearly, class structure is the most abstract of the five. Class structure is best conceptualised as a system of places generated by the prevailing social relations of production through the medium of institutions which set limits on people’s capacity for action. For example, it will place limits on the resources (and especially the forces of production) that institutions have available and that people can call upon. The basic feature of class structure is still, and will be as long as a society remains capitalist, the exploitative relations of production that are based upon the amassing of the surplus labour of one class by another via the ‘free’ exchange of labour power. This relation ensures the existence of a class of wage labourers and a class of capitalists.

The problem then becomes what other relations of production are to be treated as distinctive determinants of class structure. Marx would certainly have included the form of possession of the means of production (property rights) and the degree of domination over production (the control of the labour process). Other commentators add in other relations. The criteria differ. For example, some commentators include the point at which they envisage the capitalist mode of production appearing in full flight. Thus Wright stresses the importance of the control of investment (money capital). Other commentators also include relations forged within the development of capitalism which hail the arrival of new ‘submodes of production’. For example, control of business organisations becomes an important determinant of class structure under corporate capitalism. The list can be extended much further (see Walker, 1985a) to encompass the division of labour, the form of the labour market, and so on. While this may seem a rather frustrating exercise it is not a trivial one. On decisions as to what relations of production are chosen as distinctive determinants of class structure rests the system of class places which is generated with which to pursue class analysis. The exercise becomes particularly important in defining a middle class or middle classes (see below).

There are certain clarifications of the concept of class structure which need to be addressed. First, it is important to realise that stating that a particular class structure limits institutions or people’s capacity to act in certain ways is by no means the equivalent of saying that class structure alone determines action. There is no unproblematic mapping of class structure onto social and political life. Other autonomous or relatively autonomous social forces quite clearly act within the limits described by class structure such as race, religion, ethnicity, gender, family and various state apparatuses, not only blurring the basic class divides but also generating their own social divisions (Wright, 1985). This is a conclusion to which the Marxist literature has come slowly and painfully over the last twenty years – class is not the be all and end all of social and political life. Its ability to set limits to action can be quite limited (although, given the nature of capitalist societies it is never non-existent). Not only that. These other social forces can act through distinctive institutions to alter the relations of production in ways which can be quite important. Think only of the differences in the cultures of Japanese capitalism and United States capitalism (Morgan and Sayer, 1985). Second, class structure cannot and must not be seen as some kind of deus ex machina hanging over the stage of social life, and periodically descending to point actors in the direction of particular class places. Class structure is always and everywhere tentative. It has to be reproduced at each and every instant. Clearly institutional momentum will often ensure this but it can by no means be guaranteed. Third, the existence of class structure can only be the beginning of any class analysis which is not on the grandest of scales. Class structure is only one element of class and it is unfortunate that in the literature it has too often become an end in itself.

In many ways, the concept of the formation of classes is of more importance. We take it that class formation refers to how people are recruited to class places through institutions which are numerous, diverse and overlap. The concept is more problematic as well because it involves such a high degree of contingency; there are many possible ways in which a system of class places can be formed according to the number of institutions that can be found in a particular society, at a particular time, the mix of those institutions and the degree to which each institution embodies class practices. ‘Thus in each concrete conjuncture struggles to organise, disorganise, or reorganise classes are not limited to struggles between or among classes’ (Przeworski, 1977, p. 80). What is clear, then, is that any analysis of class formation as a historically contingent process arising out of reciprocal actions must step outside the social relations of production and venture into social relations of reproduction. Further, these social relations of reproduction cannot be seen in the narrow sense as just concerned with the reproduction of labour power. Many of them are bent towards reproducing practices which may only tangentially interact with class practices or, indeed, may be divorced from them; ‘culture’ rears its problematic head. Quite clearly, the implication is that the analysis of class must be broadened out to the analysis of social classes.

The study of the formation of social classes requires the development of at least three associated concepts; class conflict, class capacity and class consciousness. It may well be true that the basic exploitative and antagonistic divide of class structure between capital and labour guarantees some degree of class conflict for that divide generates a gradation of wealth. But class conflict involves much more than this. It involves struggles among classes (and alliances between them) which are not constituted just out of the relations of production around issues which are not just concerned with the relations of production. More than this even, it involves struggles about whether classes will take shape at all. Thus the distinction between ‘class struggle’ and ‘classes in struggle’. Until quite recently, with a few exceptions, the importance of class conflict tended to be underemphasised in Marxist writings – class conflict too often tended to be thought of as something ant-like going on at the interstices between the two warring blocs of capital and labour. In the last few years, however, under the stimulus of Thompson’s (1965) The Making of the English Working Class and then Przeworski’s (1977) raising of Kautsky (see also Przeworski, 1985) the importance of class conflict has been reaffirmed, most especially in work on the evolution of the labour process as encapsulating a history of struggle at the point of production (e.g. Friedman, 1977; Burawoy, 1977, 1985; Stark, 1980) but also in the more general context of the history of working-class politics (e.g. Foster, 1979; Cleaver, 1979; Groh, 1979; Joyce, 1980).

Once classes are thought of as being formed by the battles they have to fight, then the mode and degree of class organisation becomes a crucial determinant of classes’ ability to reproduce themselves. Certain types of organisations will be more or less effective, enabling a class to exert more or less of its powers in the service of particular causes. Conventionally, the effectiveness of a class organisation in linking individuals together into a social force is referred to as class capacity (Wright, 1979) or class connectedness (Stark, 1980). Recently work on class capacity has become more common. Stark (1980, p. 98) sums up the general thrust of this work as well as any other:

organisations may be informal (based, for example, on interactions within the work situation or on the networks of kinship or residence) or formal (craft organisations, trade unions, professional associations, firms, state agencies, political parties, etc.). But in both cases their interests, capacities and resources are not posited a priori by the analyst but emerge historically, subject to changes in direction and magnitude based on the shifting patterns of relations (of conflict and alliance) within and between organisations. A relational analysis which focusses on the interaction of organisations (rather than on the attributes of individuals or the global properties of modes of production) is not incompatible with class analysis, but, in fact, is inseparable from it … it becomes apparent that a class never exists as a single collectivity-in-struggle but as a multiplicity of collectivities-in-struggle. The study of the forms and dynamics of these groups is the task of class analysis.

This is not, of course, to say that certain classes in capitalism do not start with some organisational advantages. Offe and Wiesenthal (1980) have shown how the organisation of the capitalist class is beneficially affected by the fact...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- 1 The geography of class formation

- PART ONE THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

- PART TWO THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

- Bibliography

- Index of Names

- Subject Index