![]()

Part I

Theory

![]()

1 Apocalyptic Security

Biopower and the Changing Skin of Historic Germination

Lee Quinby

INTRODUCTION

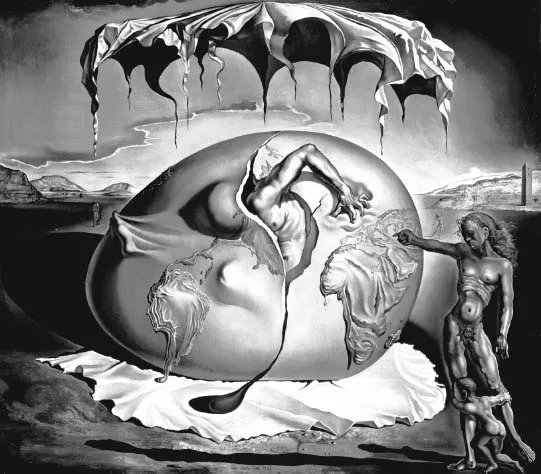

Figure 1.1 Salvador Dalí, Geopoliticus Child Watching the Birth of the New Man (1943). Oil on canvas, 18×20 ½ inches.© Salvador Dalí. Fundación Gala-Salvador Dalí (DACS), 2014. Collection of the Salvador Dalí Museum Inc., Saint Petersburg, FL, 2014.

One of Salvador Dalí’s most arresting works is a painting entitled Geopoliticus Child Watching the Birth of the New Man. I first saw it at the Dalí Museum at the turn of the Millennium, a fitting time to view a painting so ripe with apocalyptic and millennial themes. As a scholar of American apocalyptic belief, I was perhaps overripe myself for experiencing the work as a kind of epiphany, but ever since that initial viewing, I have found myself haunted by its capacity to simultaneously convey both the appealing and the appalling elements of apocalyptic thought. Created after Dalí moved to the US in 1940, and dated 1943, a time when much of the world was torn apart by the Nazi geopolitical doctrine of aggression known as Geopolitik, the painting portrays both the ravages of war’s destruction and the corollary desire to begin again with renewed power and promise. In contrast to the enigmatic juxtapositions of Dalí’s 1930s surrealist style, this work is in keeping with his classic period in which Catholic symbolism converges with current events to produce social allegory. The artist’s own abbreviated notes about the work are as enigmatic as they are striking: “Parachute, paranaissance [sic], protection, cupola, placenta, Catholicism, egg, earthly distortion, biological ellipse. Geography changes its skin in historic germination” (Dalí Museum website; see www.thedali.org).

As with the painting’s tantalizing title, these words mingle abstract mystification with concrete embodiment, a fusion that replicates the apocalyptic paradigm in which images of otherworldly tangibility are employed to depict both the cosmic devastation of the world and the transformed earth of the New Jerusalem. Taken in this light, the painting encapsulates the traditional apocalyptic motif of renewal out of destruction. As an ancient Jewish and later Christian system of belief, “apocalypse” is understood to mean truthful revelation about the divine obliteration of time, most of humanity, and the world, accompanied by the bestowal of eternal reward on the chosen people. At the same time, however, as historical occurrence in which the world as one knows it has dramatically altered, apocalypse has always involved power relations that are geographically specific and politically motivated. With today’s ever-intensifying technological prowess, these power relations are increasingly proliferative and transformative of life itself. Apocalypse, in other words, has always been a geopolitical phenomenon and is also increasingly a biopolitical one, propagating new parameters of power over time. Or, to play on Dalí’s discerning comment, apocalypse has changed “its skin in historic germination.”

Paramount to this chapter is the view that certain features of traditional apocalyptic belief continue to shape relations of power in the twenty-first century. Among these is a tendency toward moral absolutism built on stark divisions between good and evil. So, too, there is a sense of conviction that an apocalyptic scenario is unavoidable. Yet I also want to emphasize that the form that apocalyptic belief takes in our time has gravitated toward growing moral uncertainty and ambivalence about its imminence as well as its trigger. In other words, a newer domain of power—what Michel Foucault called “biopower,” the “power to foster life or to disallow it to the point of death” (Sexuality 138)—has also reshaped apocalyptic thought. In this chapter, I argue that this transformation has brought about an oxymoronic rationality—what I call “apocalyptic security”—that perilously guides practices at levels ranging from the individual to the global network of nations.

Here again Dalí’s painting is suggestive, with a number of intriguing elements that correspond to traditional apocalypticism and others that reflect significant changes within apocalypticism that became especially pronounced over the last half of the twentieth century and continue to transform the belief system in the twenty-first. The argument that follows has four parts. In the first section, I offer a reading of Dalí’s painting meant to highlight geopolitical and biopolitical processes of “historic germination.” The second section draws on Foucault’s discussion of “governmentality” in order to provide a brief history of the conditions of modernity that knitted together the relations of sovereignty and biopower through an apparatus of security. In doing so, I seek to illuminate the role that apocalypticism has played in this process. This form of inquiry is in keeping with what Foucault called a “critical ontology of ourselves [ … ] in which the critique of what we are is at one and the same time the historical analysis of the limits imposed on us and an experiment with the possibility of going beyond them” (“Enlightenment” 319). In the third section, I point to vicissitudes within apocalyptic thought that emerged when governmentality linked both apocalypse and biopower to the goal of security, resulting in persistent equivocation about knowledge and human identity. In the final section, I suggest that this historical combination of conditions has provoked what Foucault called a “problematization” in regard to apocalyptic belief and that therein lies one of the most crucial ethical-political challenges of our time.

THE REGARD OF THE UNRULY

Dalí’s title for his painting directs attention to two poles of kinetic energy, the “New Man,” at the painting’s center, who struggles to be born, and the “Geopoliticus Child,” in the lower right-hand corner, who crouches in fearful watch at the event. Against a wasteland of desolate earth and a sky variegated by amber hues and metal gray clouds, the Man struggling to emerge from the large globe-mapped egg breaks through where the rising power of the US would be. Flanked on either side by the expanding continents of Africa and South America, his left hand bears down on Europe as he gains support to pull himself out. Dalí’s note regarding “earthly distortion” thus points to an alteration not only in the European mapping of the world, but also in the way power might potentially shift away from those imperialist nations to the resource-rich continents of the developing world. In mesmerized fascination, Geopoliticus Child simultaneously shrinks back and ventures forward, while casting a long shadow that runs beneath the expanse of the egg-shaped globe. Unlike the designated New Man, whose gender is explicit, Geopoliticus Child’s gender remains unmarked, since we have only a back view of the naked figure whose sturdy body and close-cropped hair could be that of either a girl or boy. The effect is to extend the Child’s act of witnessing the birth to both genders.

Significantly missing from the title is any mention of parental relation. Perhaps this omission is what Dalí’s notes meant by the phrase “biological ellipsis.” The New Man, apparently, is not to be thought of as father of the Child. Nor is the Child metaphorically “father” to the Man. Instead, the title’s chronological reversal depicts Geopoliticus Child witnessing the birth of the New Man, who is born fully formed and ready to act in and upon the world. Because the title specifies the act of the Child witnessing the scene, the two figures seem to stand distinct from each other rather than symbolically representing the Child who becomes the Man. In this sense, both the title and the painting suggest that the New Man has given birth to himself, thus making literal the capitalist mythology of the self-made man who denies obligation to parents and offspring alike.

Equally notable is the title’s total omission of the painting’s third key figure. This is the figure upon which from lived experience and political-philosophical concern I most tend to align myself, for the omitted figure is that of a woman. (Some descriptions of the painting indicate that the gender of this figure is also indeterminable, but that seems to me to be an echo of the title’s omission of the presence of a woman.) Strikingly androgynous in physical form, her legs are muscular while her torso is emaciated, with a rounded belly slightly protruding beneath visible ribs and small breasts. Her unmanageable mane of hair matches the coloration of both the desiccated landscape and the still vital continents on the globe. Her right arm stretches out to direct the Child’s sight to the scene of birth as Geopoliticus clings to her knees for protection. In contrast to the long shadow cast by the Child, hers is truncated. Her absence from the title does not seem to be accidental, but, rather, another way of saying that the reproductive female body that (perhaps) produced the Child was not needed for (or will be denied in) the “historic germination” of the New Man. Although it is she who directs the Child’s gaze toward the scene of the New Man’s birth, her omission from the title effectively ousts her from both history and myth in the making. Such omission thus carries on the traditional form of apocalypse, which emerged out of a patriarchal culture, and in which unruly women, like the Book of Revelation’s Jezebel, are deemed a threat to truth and the divine order of things. And yet the painting’s portrait of her forces the viewer to regard her with considerable attention. Is she warning the child away from or urging her/him toward the figure of the New Man?

While it thus seems clear in the painting that Geopoliticus Child will receive whatever the New Man reaps, whether that will be reward or ruin remains as ambiguous as the Child’s unrevealed signifier of gender. Although the painting has been interpreted as a utopian tribute to the future and to the power of the US, from a feminist perspective, the figure of the New Man takes on ominous overtones. Yet, it is the painting’s ambiguity—that is, its refusal to pin down what the future holds in store—that rescues it from its otherwise robust impulses of apocalyptic desire and stations it in the realm of equivocality. So, too, mystery surrounds the three other inhabitants of the desolate land outside the globe. So small that they can almost go unnoticed, the naked figure on the right side of the globe and the clothed couple clinging to one another, on the left, behind it, remain enigmatic in relation to each other and the New Man. As social allegory, the painting maintains an elusive stance about the role of the new geography taking form. Indeed, in this depiction of “historic germination,” the pool of crimson blood spilling from the egg onto the pristine placenta-like cloth below evokes not just hopes of birth and renewal, but also fears of death and ultimate destruction at the hands of the New Man, whose struggle to be born transforms geography’s skin.

SECURING APOCALYPSE

Foucault’s most succinct discussion of modernity’s shift from sovereign power to biopower for Western nations may be found in his 1978 analysis of “governmentality.” In that essay he provides a suggestive history that casts light on how power relations over territories and power relations over life converged in the modern era and gradually produced the dominant system of biopower relations that now undergirds the Western state but is hardly limited by or to it. Prior to that pivotal point in Western history, the sovereign rule of the Roman Empire held sway, bolstered by doctrines and images of apocalypticism. The sovereign’s right of death over his subjects paralleled a sovereign God’s righteous apocalyptic destruction of the earth and most of the people on it. Indeed, sovereignty and apocalypse never quite disappear. As Foucault states in a lecture given two years before the essay on governmentality:

Throughout the whole of the Middle Ages, and even later, the theme of perpetual war will be related to the great, undying hope that the day of revenge is at hand, to the expectation of the emperor of the last years, the dux novus, the new leader, the new guide, the new Führer; the idea of the fifth monarchy, the third empire or the Third Reich, the man who will be both the beast of the Apocalypse and the savior of the poor. (Society Must Be Defended 57)

Just as the implantation of apocalyptic belief aided the rise of the Roman Empire and the rule of the “Church Militant and Triumphant,” so, too, the Reformation’s counter-apocalyptic force enacted a challenge to the power of Rome and helped spark a new regime of “prophecy and promise” (Society Must Be Defended 71). The shift to biopower and governmentality is thus not the first sign of apocalypse’s changing skin. One reason that apocalyptic belief has endured over millennia is because of its chameleon-like ability. That quality, and its promise of a righteous reckoning against one’s adversaries, is what allowed it to be integrated into the system of governmentality.

Foucault defines governmentality as the “ensemble formed by the institutions, procedures, analyses, and reflections, the calculations and tactics that allow the exercise of this very specific albeit complex form of power, which has as its target population, as its principal form of knowledge political economy, and as its essential technical means apparatuses of security” (“Governmentality” 220–21). This nexus of power relations and knowledge simultaneously circumscribes and generates modern citizens as members of nations that are primed to confer security on their populations and also increasingly emphasizes intertwined relations of global security. As the following section will indicate, it is this emphasis on establishing security that has most altered apocalyptic belief in the era of biopower, especially since the time of World War II.

Historically, Foucault argues, the process that led to governmentality began in the sixteenth century with a shift away from a concern about how the prince should rule over his domain to questions about how he should enact an “art of government” within it. The focus on security that emerged during this time resulted from two primary changes in Western life. The first entailed the centralization of the state that followed from the decline of feudalism. In this process, territories were consolidated under the control of the prince, who then had to find ways to maintain that control—in Machiavelli’s terms, to manipulate those forces so as to retain power over his principality and its subjects. The promise of securing the population against outside forces was indispensable to this control, but the process of bringing it about shifted gears away from the power of the prince over the state to a concern with the state itself.

The second key movement was an intensification of questions about the kind of spiritual rulership that would be necessary for the governed to achieve their salvation. These questions arose out of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, which, in contrast to the unification of the state, entailed religious dissent and diffusion of belief about what would bring about salvation, or eternal security. The new emphasis was largely directed toward worldly concerns involving the health and well-being of believers, but it also retained otherworldly notions associated with its religious ancestry, particularly apocalyptic divisions between the chosen and the damned. Such concepts, already undergirded by an opposition between the natural and unnatural, were eventually translated into normal and abnormal over the course of the twentieth century.

As a means of procuring the art of government—that is, managing the conduct of souls, individuals, and populations—two essential and related channels of biopower were developed that worked to materialize the new administrative kind of state and the particular rationality that came into being along with it. One channel was the establishment of the police as a means to ensure “acceptable” behavior within the nation. Surveillance and superintending of individual citizens were thus structured into the goal of aiding their security along with a moral disposition about what constituted suitable behavior. The second channel was the integration of economy into the national domain. Prior to this, the family was the central unit of economy, understood as household wealth, which was managed by the father. During these centuries, a gradual shift occurred in which state governance increasingly acquired the responsibilities formerly required of the family.

From the eighteenth century on, as Foucault describes it:

to govern a state will mean, therefore, to apply economy, to set up an economy at the level of the entire state, which means exercising toward its inhabitants, and the wealth and behavior of each and all, a form of surveillance and control as attentive as that of the head of a family over household and his goods. (Power 207)

This dual trend of police and nationally regulated economy reduced the power of the sovereign and the law without displacing them altogether. Instead, sovereignty became understood as “obedience to the law” rather than directly to the prince. Thus, governmentality, Foucault explains, did not supplant sovereignty, but rather consists of a “triangle, sovereignty—discipline—government, which has as its primary target the population and as its essential mechanism the apparatuses of security” (Power 219).

When eighteenth-century principles promoting the national security of citizens took hold through these dual channels of the police and political economy, sexuality became a primary focus of this new rationality, and apparatuses of security were set up to surveil it. This was fac...