- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Signal Processing, Speech and Music

About this book

This text offers a comprehensive introduction to the theory of signals and systems and the way in which this theory is applied to the study of acoustic communication (both digital and analogue): the development of systems for producing, transmitting and processing speech and music signals. The book is designed to make the reader acquainted with the refined and powerful theoretical and practical tools available for this purpose.;The book teaches understanding of such concepts as amplitude and phase spectrum, impulse and frequency response, amplitude and frequency modulation, as well as such methods for the analysis and synthesis of speech and musical systems like LPC and wave shaping. The use of complex numbers is avoided and a knowledge of mathematics beyond that of secondary school level is not necessary.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Signal Processing, Speech and Music by Stan Tempelaars in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

MusicCHAPTER 1

Acoustical Communication

Acoustical communication is possible thanks to the fact that we have an organ that is sensitive to pressure fluctuations in the medium (air) in which we live. A similar or analogous organ is to be found also in more primitive beings and here the function of this organ is clear: it warns the organism of danger and makes it aware of the presence of food etc. This is the primary function of our hearing organ. The sound signals here are irregular and often pulse-like (the breaking of a twig, the falling of a stone, the noise of water etc.). This fact is very important for a proper insight into the functioning of the ear. For perception experiments, for example, we should not restrict ourselves to regular stimuli such as sinusoidal vibrations. This holds especially for directional hearing because this ability is directly connected with the warning function of the hearing organ. Also the strong tendency people have to identify unknown sounds (for example electronically generated sounds) can be related to this function.

The ‘pressure sensitivity’ is in fact a sensitivity to pressure changes where the pressure fluctuation must be greater than a particular threshold level to excite the nerves. This threshold level is not constant but depends among other things on the ‘speed’ of the vibration (still better: its ‘frequency’, but this term is introduced later in the next chapter). When the pressure fluctuations are too slow, they no longer integrate into a sound impression. I will deal with this aspect further on in this chapter. At the upper boundary there is much variation. The limiting factor here is the mass of the vibrating parts of the hearing organ. With fast vibrations most of the sound energy is converted into heat in the middle ear and does not reach the sensory cells in the inner ear. A high upper threshold is therefore to be found in small animals (with sound vibrations in water and thus with sea creatures the situation is different). The upper threshold is also dependent on age, sex and other factors. Between these two limits there is still a wide range of audible sounds that are also available for the second function of the hearing organ, the communicative function, which is the consequence of the ability of the higher animals to produce sound vibrations themselves. This led to certain applications such as the ‘radar’ system of bats, but much more important was the possibility of communication between members of a species in connection with reproduction, collection of food, mutual defence etc. Here a curious phenomenon occurs: with our muscles we indeed can produce air pressure variations, for example, by waving our hands, but as these fluctuations are rather slow, the produced sound waves have wavelengths that are relatively long (between tens and hundreds of meters) compared to the dimensions of the source of the vibrations, the human body. This is important because to radiate a signal efficiently the source dimensions should be of the same order of magnitude as the wavelength. A violin for example radiates wavelengths between 0.22 and 1.7 m, a double bass between 1 and 8 m. With our muscles we can only produce sounds effectively via clapping the hands, drumming, hitting, stamping etc., i.e. by interrupting a movement and not by the movement itself. The repertory of such sounds however is far too limited to function as the basis for a high-level communication system. Thus the human body is a very inefficient source of the sound vibrations that are required for acoustical communication.

The solution to this problem has been the development of a special organ in many animals and in man to make acoustical communication possible. In man this is the voice. With this organ air vibrations with the necessary speed characteristics (easily perceivable, efficiently transmittable) can be produced. Simplified the principle of voice production is as follows: with the muscles of the thorax and diaphragm the air in the lungs is compressed. This air can only escape via the trachea by pressing apart the vocal chords that normally shut off the trachea. After a very short time the vocal chords are closed again by the aerodynamic effect of the escaping air. This process is repeated so quickly that 60 to 300 times a second a small portion of air escapes. These periodic air pushes produce a sound vibration with the speed properties required for a sound to be audible. These vibrations come thus into existence with the help of muscle energy but not as ‘muscle vibrations’. Information is coded into this signal via (slow) changes in the parameters of this fast vibration, because

- a slow vibration is not audible

- a slow change in a fast vibration is audible.

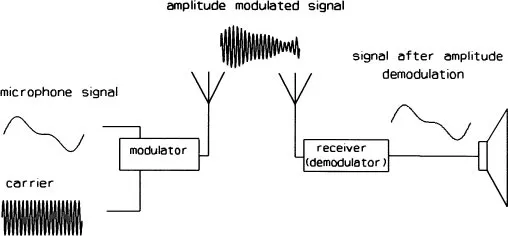

Here a comparison can be made with the technical process of modulation used in radio and television transmissions. Only many years after the invention of this technique the resemblance to the process of speech (and music) production was recognized. In speech and music we see ‘natural’ examples of modulation that, in radio technique, is applied for the same purpose, namely that of improving the signal transmission. After amplification an electrical signal can be broadcast as an electromagnetic fluctuation with the help of an antenna. Due to the enormous speed of the electromagnetic waves, the wavelength would be so large that for an efficient radiation the antenna would have to be of an absolutely impossible size, and, what is more, signals coming from different transmitters would be difficult to distinguish from each other. Therefore, modulation is applied: in the transmitter a fast, stationary vibration, the so-called ‘carrier wave’ is generated. When a signal is to be broadcast, the maximal deviation of this vibration is made to correspond with this signal. Here we speak of ‘amplitude modulation’ (AM). (In radio technique other forms of modulation are employed as well). This process can be seen in the figure below (fig. 1.1):

Figure 1.1 Amplitude modulation in radio transmission.

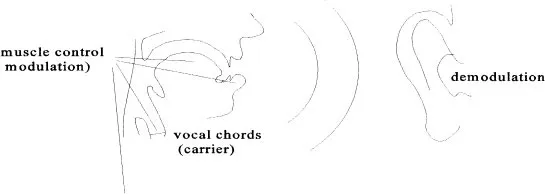

Due to the much higher speed of the vibration the antenna size can be kept to a reasonable level and by tuning the receiver (in which, by means of a process that is called ‘demodulation’, the original signal can be derived from the modulated one) to the carrier wave the signal can be distinguished from other signals with different carrier waves. Furthermore due to modulation, signals are less ‘vulnerable’ which means that they are not so easily distorted by interferences. This holds as well for speech as for musical signals. Along with making the transmission efficient, modulation makes the signal more robust; it remains detectable also under difficult circumstances. The modulation is much more complicated than with its technical equivalent because various parameters of the vibration are modulated simultaneously. In speech the system looks as follows (fig. 1.2):

Figure 1.2 Modulation in speech communication.

The carrier wave vibration is produced by means of the vocal chords and simultaneously there and higher in the vocal tract the carrier wave is modulated via (changing) the number of vibrations, the excursion and the ‘form’ of the vibration, the articulation etc.

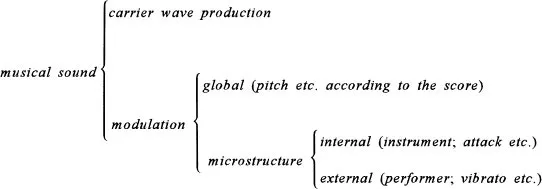

In music the same thing happens but the role of the various parameters is different. It is therefore possible to give the following scheme for the production of musical signals:

The analogy with a radio broadcast holds as well for the receiver. From the above it is clear that the perceptual process is a form of ‘demodulation’ in which the signal information is extracted from the modulated carrier wave. Having fulfilled its task, the supporting vibration is no longer required. That the carrier wave is not essential can be shown by means of the technique of Linear Predictive Coding (LPC) which will be discussed in detail in chapter seven. With LPC speech can be transmitted very efficiently by transmitting only the modulation parameters and not the carrier wave. Demodulation, i.e., separating carrier wave and modulating signal, is only possible when the frequency of the latter is below that of the former signal. In speech and musical signals this condition is fulfilled: the maximal ‘muscle frequency’ is ca. 20 Hz, which is also the lowest audible tone and thus the minimal carrier frequency.

Choosing the acoustic signal (in its electrical form) as an object for investigation thus means that we are dealing with modulated signals. We should always take this aspect into account when studying the process of signal transmission or the more general problem of acoustical communication. We shall be dealing with signals, the information carriers, and with systems that transmit and/or process these signals. Signals and systems are tightly coupled. Although we can construct an abstract mathematical model of the signal, the signal function (to be discussed in chapter 2) the real signal is always linked via its physical carrier to the system of which that physical carrier is a part (a space, an amplifier and so on).

Taking into account the modulation aspect, we can draw the conclusion that the communication chain looks as follows (fig. 1.3):

Figure 1.3 The communication chain.

The signals and systems that will be our main subject are located between the output of the modulator and the input of the demodulator. It is of interest to check whether a more comprehensive approach is possible and to include aspects of the modulation and demodulation process as well. We will discuss this question in the final chapters.

For further reading, see Mayr (1980), Plomp (1984), Corliss (1990) and Pierce (1983).

CHAPTER 2

Functions

2.1 Registrations and signal functions

One possibility resulting from the conversion of the acoustical signal into an electrical one is that of making a registration of it. Examples of registration equipment are the pen recorder and the oscilloscope. Furthermore a computer equipped with converters (see chapter 4) and graphical output is often used for this purpose. The registrations shown here were made in this manner.

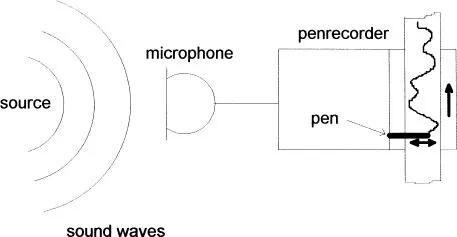

The pen recorder consists of an amplifier which increases the power of the electrical fluctuations and an electromechanical converter which converts an electrical voltage into a proportional deviation of a pen. Coupling the recorder with a microphone has the effect that the pen follows the air pressure fluctuations. If simultaneously we run a strip of paper at a constant speed under the pen, the result is a ‘registration’ of the pressure fluctuations with time (see fig.2.1.1).

Figure 2.1.1 Registration of a signal with a penrecorder.

On the next page some registrations of this type are shown: in fig.2.1.2 the registration of a speech sound, in fig.2.1.3 that of a clarinet tone and in fig.2.1.4 that of a violin s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- CHAPTER 1 Acoustical Communication

- CHAPTER 2 Functions

- CHAPTER 3 The Harmonic Oscillator

- CHAPTER 4 Signal Functions in the Time and Frequency Domains

- CHAPTER 5 System Theory

- CHAPTER 6 Systems for Sound Signal Processing

- CHAPTER 7 Analysis and Synthesis Techniques

- CHAPTER 8 Acoustical Communication Revisited

- References

- Appendix, Solutions to Problems

- Index