eBook - ePub

Sensation Seeking (Psychology Revivals)

Beyond the Optimal Level of Arousal

- 450 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Originally published in 1979, this title represents a summary of 17 years of research centring around the Sensation Seeking Scale (SSS) and the theory from which the test was derived. Now an integral part of personality testing, including adaptations for use with children, this reissue is a chance to see where it all began.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sensation Seeking (Psychology Revivals) by Marvin Zuckerman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

Nothing is constant but change.

—Slogan on the wall of a drug rehabilitation center, author unknown.

MODELS OF PERSONALITY AND THEIR SOURCES

Change is indeed a fact of life, whether we resist it or accept it. Even if we choose to remain the same, the people and situations we encounter and the world around us will change. But some creatures seek change rather than merely adapting to it. A moderate amount of change or sensation seeking has an obvious adaptive value for organisms with a capacity to acquire and retain information. New sources of food supply and general familiarization with, and even expansion of, one’s territory are an advantage to the more adventurous, exploratory type. Sexual, aggressive, and much normal social behavior require some tolerance for the relatively novel and arousing situation. However, it is also likely that organisms that are too adventurous and sensation seeking will take risks that may reduce their survival chances. As with most other traits, evolution has probably produced variations about an optimal level of the trait.

My dog Babar spends a lot of time running around and sniffing at various objects, dogs, and persons. His “voyeurism” knows no limits. He peers in neighbors’ picture windows and climbs up on automobiles to stare at the drivers. The pictue in Fig. 1.1 shows an incident that happened one day while he was excitedly exploring a beach. He came across a novel object, one that he had never smelled or seen before, a horseshoe crab. The picture shows the ensuing investigation, resembling an eager researcher poring over his or her data. A moment later he seized the shell, tossed it in the air, and ultimately demolished it. Fortunately the crab no longer inhabited it. Play can be a destructive activity. The sequence of orienting, investigation, play, and eventually habituation and ignoring is a common one in most mammals reacting to novel stimuli. Most behavioral theories discuss the effects of previous reinforcements, but have little to say about reactions to novel stimuli or play.

FIG. 1.1. Dog approaching a novel object.

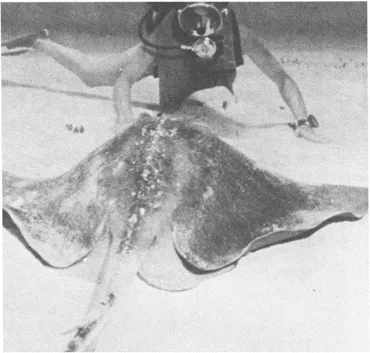

Why do dogs and people (Fig. 1.2) explore the novel and seek new experiences? Why do we risk upsetting our stable, comfortable, and predictable social arrangements to make personal and collective revolutions? Why do we ski and race our cars at excessive speeds, fully aware of the risks in these unnecessary activities? Why do we disturb the healthy, homeostatic balances in our bodies with the drinking of alcohol, ingestion of drugs, jogging, and other potentially addictive and physically stressful activities? Why can’t subjects be content and happy lying for a few hours or days in a comfortable, dark, soundproof room? But all these questions should be rephrased as: Why do some persons engage in these activities whereas others behave like “normal” tension-reducing, fear-avoidant persons should? Is there a generalized trait that can subsume various kinds of risk taking, sensation seeking, and intolerance of constancy? These are the kinds of questions that led me to define the construct of sensation seeking, to devise measures of it, and to examine the relations of these measures to the kinds of variables described in this book.

FIG. 1.2. Scuba diver approaching a novel object. (Courtesy Jack McKenney Film Enterprises. Reprinted with permission.)

The idea of a sensation-seeking trait emerged from my attempts to provide a framework for the data on individual differences coming out of experiments on sensory deprivation. The first definition of the trait was based on factor analyses of a broad range of rationally constructed items, but the original construct and items were also influenced by less scientific observations of patients, friends, children, pets, and even myself. There was a need to give a definition to a range of behavioral phenomena that defied classification and explanation within existent theories.

The ultimate models that we construct do not need to have a simple, common-sensical relation to folk concepts or to provide a phenomenological feeling of truth. The physicist’s model of the physical world bears little resemblance to our perceptual impressions of reality. A biological model for human behavior may have little “face validity,” since it deals with another level of phenomena. The psychoanalyst’s idea of an unconscious mind does not seem reasonable or even rational to the average man or woman but was Freud’s attempt to explain certain significant lapses in the memories of his patients. But the constructs that we devise are eventually limited by the sources of our observations. A .mentalistic psychology such as that evolved by the structual school of Wundt and Titchner could not be applied to the data of animal behavior without producing a strained anthropomorphism. Conversely, the radical behaviorism of Watson and Skinner, developed from animal data, was strained by attempts to accommodate cognitive phenomena. Most theories have a limited “range of convenience,” to use Kelly’s expression. Freud’s construct of repression applied nicely to a range of neurotic behavior, particularly that which included hysterical conversion and dissociative disorders, but the attempts to extend this idea to the broader range of normal human memory and cognition have not been successful.

The neobehaviorism of the 1930s and 1940s produced a model of humans that portrayed them as governed by a small number of innate drives and a larger number of acquired drives and described learning as governed by the satisfaction or reduction of these drives. The limited range of convenience of this model was apparent to all but the more involved scientists ofthat time. I can remember the heat generated by the “latent learning” controversy as to whether or not anything could be learned without making a reinforced response. The argument was barely plausible when applied to rats but somewhat absurd when applied to humans. Tolman’s attempt to develop a cognitive theory, applicable to humans as well as rats, could not sway the Hull-Spence adherents who, under the banner of parisimony, insisted on working from rats to man rather than vice versa. It was not until the 1960s that Bandura and Walters (1963) provided us with a learning theory based on observations of children rather than rats and a theory that asserted that social learning is based on observation and modelling. Like most of the older learning theories, Bandura’s deliberately avoids dealing with the biological susbstrate of learning and motivation. The emphasis on cognition, and the de-emphasis of biology, provides little possibility for a broad, comparative theory of behavior.

Another curious feature of the earlier behavioristic theory was the restriction of primary motivation to the “gut drives ” of hunger, thirst, and sex. Harlow and others had long ridiculed this limitation of drive theory, pointing out that one could observe extended sequences of goal-directed behavior in the absence of deprivation of these needs. Harlow’s broader view of motivation was undoubtedly influenced by the fact that his subjects were species higher on the phylogenetic scale, monkeys and apes. Still there was ample evidence from lower species that the primary drive explanation had little relevance for most of their behavior outside of a Skinner box or T-maze. The theories had a particularly difficult time in explaining animal activity, exploration, investigation, and play in the absence of high levels of primary drives.

The reaction of most clinical and personality psychologists of the time was to reject the general behavioral theories of motivation, developed from animal laboratories, and to embrace human models, particularly the psychoanalytic ones with their limited range of convenience and even more limited empirical base of knowledge. Despite the efforts of Dollard and Miller to build conceptual bridges between behavioral and clinical theories, it was not until the advent of behavioral methods of treatment that clinical psychologists returned for a new look at the theories from which the new treatment models arose. But by now, these models are largely of historical interest. The field of learning has moved from the rat and the pigeon to the human and the computer. The area of “information processing,” as it is now called, is largely addressed at cognitive problems that reflect the functioning of the human brain with its unique capacities for symbolic transformation and organization. The area of motivation is also changing. Researchers are moving away from “gut physiology” to the study of central motivational mechanisms. This closer amalgamation of behavioral psychology and neurophysiology has been made possible by the advances in the latter field in the last quarter of a century. But despite the impact of these developments in our understanding of the brain on learning, memory, motivation, and psychopathology, most clinical and personality pyschologists remain remarkably steadfast in the exclusion of biological theory from their models of the human. The final chapters of this book represent an attempt to apply these biological models to the area of sensation seeking. Although this may be regarded as an aberrant approach, and a “reaction formation” to the prevalent environmentalism of social learning theory and clinical theories, it represents the position I have arrived at after a long journey through the theoretical realms of psychology. I am somewhat surprised to find myself there.

THE USE OF TESTS TO DEFINE PERSONALITY

The psychometric approach has developed almost independently of the laboratory-experimental approach, which led Cronbach (1957) to speak of the “two disciplines of scientific psychology” and Eysenck (1967) of the “two faces of psychology.” Despite Cronbach’s hope for a rapprochement between the disciplines of individual differences and experimental psychology, it has not taken place for various reasons that I cannot go into here (see Zuckerman, 1976a).

The study of individual differences via tests has been dominated by the rational-clinical approach and the inductive-factor analytic approach. The first attempts to measure personality in tests were Jung’s (1910) use of the word-association technique to discover “complexes” in patients and Woodworth’s Personal Data Sheet, an objective method used for screening neurotics from the armed forces in World War I. Clinical dimensions of neuroticism and anxiety continue to dominate interest in the field of personality differences.

Normal dimensions of personality have been defined by the inductive-factor analytic approach as exemplified by Cattell and Guilford. The procedure of these two investigators has been to start with a broad range of trait terms or questionnaire items and to use the technique of factor analysis to isolate basic clusters of items that are intercorrelated with each other. These clusters are given tentative names and grouped in scales, and their psychological significance is further explored through validity studies relating the factor-derived scales to external criteria. Theory plays little role in the process until after the factor dimensions are developed into scales. Eysenck has taken more of a hypothetico-inductive approach, involving the theoretical definitions of the broad factor earlier in the process and deriving predictions of relationships between test scores and experimental observations from the theory itself.

Certain broad, normal factors, such as Introversion-Extraversion, have emerged from all factor analytic approaches when second-order (broader, or higher in hierarchy of factors) factors are considered, but the structure of these factors in terms of their subsidiary factors is still debated (Guilford, 1975).

In contrast to the inductive-factor analytic approaches, some investigators have attempted to define a limited construct and to develop a test measure of that particular construct. The “construct validity” (Cronbach&Meehl, 1955) of the test is assessed in terms of its relationships with other presumed measures of the hypothetical construct or by deriving predictions of behavior based on the role of the construct in a larger theory and testing these predictions using the test as the operational measure of the construct. The latter approach is only possible when the theory in which the construct is embedded is already well defined conceptually and by empirical investigations. Otherwise, a failure to verify a prediction would be ambiguous, since it might reflect either a failure of the test or a failure of the theory. In most cases of limited domain tests, the theory behind the constuct and the test measure are developed simultaneously and interdependently; that is the way it happened for sensation seeking.

SENSATION SEEKING—OVERVIEW OF THE BOOK

The Sensation Seeking Scale (SSS) is an example of the use of construct validity in developing a limited domain theory around a test. Chapter 2 provides the theoretical background that preceded the development of the SSS. The idea of a broad sensation-seeking motive, or the need to maintain an optimal level of stimulation or arousal, goes back at least a century.

The experimentation in sensory deprivation during the 1950s and 1960s revived interest in earlier theories and led to the development of new theories. It was from this area that my own interest in sensation seeking developed. The research in this area provided a “testing ground” for the theories, and the relevant data on arousal and stimulation seeking in sensory deprivation are provided in Chapter 3. This chapter concludes with my first theory of sensation seeking, which was an attempt to explain the results of sensory deprivation, particularly individual differences in reaction to the situation.

The theories described in Chapter 2 provided little help in suggesting how the motive might express itself in stable individual differences. Chapter 4 describes how the scales were developed. The items written for the first form of the SSS represented only guesses as to the phenotypical expressions of sensation seeking in activities, attitudes, and values. This is the phase in which one’s own unscientific observations of others and oneself play an important role. The results of the first factor analyses helped shape our preliminary definition of the trait. We had thought of the trait as a consistent preference for sheer quantity and intensity of simple, external stimulation. But most of the items describing a preference for simple, intense stimulation did not correlate highly with the general factor. The items with the highest loadings on this broad factor referred to the need for varied, novel, and complex stimulation rather than for simple, intense stimulation in one sensory modality or another. Subsequent factor analyses defined four subfactors; and on the basis of these, a new form (IV) was constructed. The four factors were conceived of as alternate expressions of the underlying common trait. Later studies in England confirmed the cross-cultural stability of the four factors, and the last form (V) of the test is a shortened version containing the most consistently loading items for the four factors and a total score weighting each factor equally. Reliabilities and interscale correlations for the various forms of the SSS are also reported in Chapter 4.

Chapter 5 discusses demographic differences on various forms of the SSS, including age, sex, national-cultural, regional college, racial, and educational differences. Age and sex differences are prominent; national and racial differences are also found, but education seems to be a less important demographic variable. Regional college differences and national-cultural differences seem to be more marked in females. The implications of these findings for the question of biological vs. social determinants of sensation seeking are ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Theoretical Background

- 3. Sensory Deprivation: A Testing Ground for Optimal Level Theory

- 4. Development of the Sensation Seeking Scales: A Historical Overview

- 5. Demographic Differences

- 6. The Relationships Between the SSS and Other Trait Measures

- 7. Risk-Taking Activities

- 8. Sensation, Perception, and Cognition

- 9. Vocations, Vocational Interests, Values, and Attitudes

- 10. Experience: Sex, Drugs, Alcohol, Smoking, and Eating

- 11. Psychopathology

- 12. Biological Correlates of Sensation Seeking

- 13. A New Theory of Sensation Seeking

- Appendixes

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index