![]()

Introduction

Whither Chinese HRM? Paradigms, models and theories

Malcolm Warner

Judge Business School, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

In this introduction to this volume, we ask ‘Whither Chinese HRM?’ We explore the applicability of the concept of ‘paradigm’ to management in the Chinese context. Moving from the general to the particular, we discuss the notion of ‘paradigm-shift’ both in the natural and social sciences, moving on to the field of management studies and asking where this impinges on all things Chinese, including its HRM. A number of new original empirical studies chosen for this edited collection are then discussed vis-avis the above-mentioned themes. Of particular interest, is whether there is a dominant existing paradigm in play and what might be the prospect for the future. However, all things considered, we conclude that it would be premature as yet to say whether there is a ‘new paradigm’ emerging in the field.

Introduction

In this volume, we ask the following key question, ‘Whither Chinese HRM?’ We go on to discuss this genre of HRM as an academic subject, where it is advancing and the likely direction of its progress in terms of paradigms, models and theories. In recent years, we have explored the specific themes that we think are relevant to its evolution in a number of edited collections on the Chinese HRM model (see most recently Warner 2012, for example). Of particular interest is whether there is a dominant ‘paradigm’ (in Mandarin, they use the term, fan shi) in the field and whether there might be a new one in the making. A whole debate has also recently arisen whether there should be a theory of Chinese management or a Chinese theory of management (see, for example, Barney and Zhang 2009; Child 2009; Whetten 2009) which we go on to address later.1

In this contribution, we shall first discuss the applicability of the concept of ‘paradigm’ to management in general and to HRM in particular (see Table 1). At this point, we take for granted that the reader is familiar with the discussion of such paradigms in natural science, principally by scholars such as Kuhn (1962), the well-known historian and philosopher of science (see Fuller 2000), in his path-breaking work half a century ago, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, as well as its relevance to social science by a number of economists, such as Coats (1969), Blaug (1975), Stiglitz (2011) amongst others.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines a paradigm as a pattern or model or world view underlying a theory (OED 2009). Kuhn himself defines a scientific paradigm as a: ‘universally recognized scientific achievement … that, for a time, provide[s] model problems and solutions for a community of researchers’ (Kuhn 1962, p. 1). His main thesis is that scientific fields are characterized by periodic ‘paradigm shifts’ – rather than just proceeding in a linear and continuous direction. He adds here that: ‘The scientific community is a supremely efficient instrument for maximising the number and precision of the problem[s] solved through paradigm change’ (Kuhn 1962, p. 168). Note might be taken, however, as to the criticisms made invoking the notions of philosophers of science, such as Lakatos, Popper and Polanyi (see Blaug 1975, pp. 154 – 155 on some of these caveats). To be fair, Kuhn in the second edition of his book (Kuhn 1970) did make some concessions vis-a-vis his thesis of ‘discontinuities’ in science, pointing out that the argument might concern minor, as well as major shifts in knowledge generation. Even so, Lakatos remained critical of Kuhn’s relativism and believed that science advanced by ‘scientific research programmes’ rather than theories (Blaug 1975, pp. 154–155).

Table 1. Selected uses of the term ‘Paradigm’.

Paradigms in natural sciences |

Paradigms in social sciences |

Paradigms in management |

Paradigms in HRM |

Paradigms in Chinese management |

Paradigms/sub-paradigms in Chinese HRM |

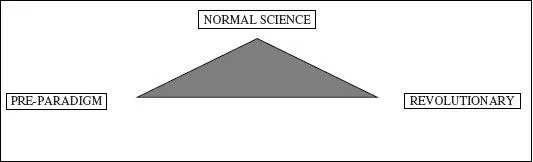

Kuhn (1962) distinguishes between three phases of paradigmatic evolution in the knowledge generation process. The first is the ‘pre-paradigm’ phase, in which there is no consensus on any particular theory, amongst many incompatible and incomplete theories. If scientists can come to a consensus on a given position, he argues, they arrive at the second phase which he calls ‘normal science’ and which becomes active within the context of the dominant paradigm. As long as there is consensus within the discipline, he continues, normal science may be consolidated. In time, normal science may then reveal anomalies where essential weaknesses in the old paradigm become apparent. Kuhn calls this ‘a crisis’, leading to the third phase, namely ‘revolutionary science’, in which the assumptions of the field are anew brought into question and an emergent paradigm is hailed. After the new paradigm’s pre-eminence is established, scientists can work with the emerging new ‘normal science’, solving puzzles within it and asking new questions (Kuhn 1962, p. 139). The cycle can subsequently be repeated over and over again, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Early users of the term ‘paradigm’ in management studies were the social theorists, Morgan and Burrell, in their book Sociological Paradigms and Organizational Analysis: Elements of the Sociology of Corporate Life (1979). This work used four paradigms, radical humanist, radical structuralist, interpretive and functionalist ‘based upon different sets of meta-theoretical assumptions about the nature of social science and the nature of society’ (Burrell and Morgan 1979, p. x). To be placed in a distinct ‘paradigm’ is to see the world in a special way, Burrell and Morgan argue. But Morgan does not use this term much in his later single-authored text on Images of Organizations, offering only one indexed item (1997). He notes that Kuhn’s concept of ‘paradigm change’ has become a part and parcel of the ‘managerial concept and ideology for reshaping management practice’ and goes on to argue that ‘any book on creative management develops implications of this approach’, so that problem-solving is helped by the fine-tuning of dialectical skills (Morgan 1997, p. 407).

Figure 1. Kuhn’s three-stage cyclical model.

Another original exploration of the term ‘paradigm’ in management was made by Donaldson in his book, American Anti-Management Theories of Organization:A Critique of Paradigm Proliferation (Donaldson 1995), around the same time. His work is a critique of developments in the study of organizations in the US at the end of the past century. He argues that there had been a profusion of ‘new paradigms’ in the literature there and that this had ‘fragmented’ the field. Many such paradigms, he thought, shared a negative ‘antimanagement’ cast. He looked at five major, contemporary US theories of organizations: population–ecology, institutional, resource-dependence, agency and transaction–cost economics. Donaldson wants to reintegrate the field by taking structural contingency theory as the core theory and adding to it selective propositions from the newer paradigms. However, Donaldson sees major theory shifts as paradigmatic, but one might argue that this is stretching the term somewhat.

A prominent writer on management who carried the paradigm debate further, specifically within the management field, was Drucker (1998), who explored the theme in his plain, down-to-earth English prose style in a widely-read article, later published in a book version (Drucker 1999). He argued that:

Basic assumptions about reality are the paradigms of a social science. These assumptions about reality determine what the discipline focuses on. The assumptions also largely determine what is pushed aside as an annoying exception. Get the assumptions wrong and everything that follows from them is wrong. (Drucker 1998, p. 152)

Moreover, he argues:

These assumptions that determine what we pay attention to and what we ignore are usually held subconsciously by the scholars, the writers, the teachers, the practitioners in the field. Thus, they are rarely analyzed, rarely studied, rarely challenged – indeed rarely even made explicit … Because the generally held assumptions about management no longer apply, it is important that we first make them explicit, and then replace them with assumptions that better fit today’s reality. (Drucker 1998, p. 152)

He concludes that in areas of study such as management, assumptions are probably more important in the natural sciences, where – ‘[t]he paradigm – that is, the prevailing general theory – has no impact on the natural universe’. In a social science field, such as management, he argues, we are dealing with something that affects the behaviour of people and human institutions. Here, ‘[t]he social universe has no “natural laws” as the physical sciences do. It is thus subject to continuous change. This means that assumptions that were valid yesterday can become invalid and, indeed, totally misleading in no time at all’ (Drucker 1998, p. 153).

In the past decade, it would appear that there has been somewhat less interest in management paradigms. It is now 50 years since Kuhn made his mark and over time the term he used, ‘paradigm’, has passed into a rather more diffuse usage. In the natural sciences, we can speak for instance of a ‘Newtonian’ paradigm, or an ‘Einsteinian’ one but in the social sciences there have been less dominating exemplars. In economics, there were a few so-called intellectual ‘giants’ such as Smith, later Marx and after him, Keynes, whose own contribution led to the so-called ‘Keynesian revolution’ and this may indeed be seen as a ‘paradigm-change’ (Blaug 1975, p. 160).

In generalizing about management, Witzel and Warner (2013) have noted the following regarding equivalent figures in this particular field:

The ‘paradigm shift’, from thinking about management to management theory and management systems, began with Frederick Winslow Taylor … Notwithstanding the important influence and ideas of earlier thinkers such as Niccolo Machiavelli, Adam Smith and Charles Babbage … we decided to start with the paradigm shift mentioned earlier, the emergence in the 1890s and 1900s of complete and coherent ideas about management … With respect to depth, here we were concerned with the degree to which each theorist helped to alter the paradigm in the field, a much rarer quality, with minimal contribution at one end and maximal at the other … [arguing that] to some extent, each of the figures or schools described … helped to change the way we think about management and added significantly to the further development of management theory. Of course, none of these figures worked singlehandedly or in isolation[we continued] … each worked with their colleagues, their forerunners and their followers and they need be considered as both revolutionary … [as well as] … evolutionary figures.

In the management theory field, for example, we perhaps can speak of the onset of the ‘Taylorist’ paradigm but we thought it was arguably doubtful to label the contribution of less-cited theorists as possibly ‘paradigmatic’ (Witzel and Warner 2013, p. 1–2).

An approximation of how widespread the citation of the different versions of the term ‘paradigm’ in the management literature by academics in the field has been revealed in Google Scholar.2 The highest citation score in management generally found was for the work of Stevenson and Jarillo (1990) who focussed on a paradigm of entrepreneurship, with 1449 mentions; this was followed by the contribution of Boxall and Purcell (2003) on the strategic HRM paradigm, which attempted to integrate HRM theory with practice to reveal the role HRM might play in organizational performance, with 934 instances.

Turning now to the ‘Middle Kingdom’ (Zhongguo), we may well ask if there is in fact a distinct ‘Chinese management’ paradigm? A substantial number of books and articles are available on business and management in the Chinese context in general, but only a limited number of these achieve a high number of citations, such as the work of Redding (1993) on Overseas Chinese managers, with 1947 citations.3

One of the most important theoretical papers on Chinese management in the mid-1990s by Boisot and Child (1996) on fiefs, clans and network capitalism, regarding the institutional mesh which holds together in a new form of economic organization they call ‘network capitalism’, has, at least, an ‘implicit’ paradigm. They observe that: ‘China’s rapid economic development is being accomplished through a system of industrial governance and transaction that differs from Western experience. Here, we identify the broad institutional nature of this distinctiveness within a framework of information codification and diffusion’ (Boisot and Child 1996, p. 600). This article has 643 Google Scholar citations, a relatively high score for this field.

Around the same time, Boisot (1996) had argued that:

The changes experienced by the managers in socialist and post-socialist state-owned enterprises can be likened to what Kuhn … has termed a ‘paradigm shift’, a transition between two systems that are incommensurable. Yet, as Kuhn himself has pointed out, individuals do not easily give up on the way that they see the world. A new paradigm often only really takes root when the advocates of an earlier paradigm die off.

Boisot (1996) examined what he calls ‘the paradigmatic role played by the labour theory of value in accounting’ vis-a-vis the behaviour of state-ow...