![]()

VI

Mediaeval Sites: Part One

1. INTRODUCTION

THE obstacles to the archaeological exploration of mediaeval sites in London are even more daunting than those that impede a study of the Roman remains. While over a large part of the central area of the city the depth of the accumulations is such that the Roman levels survive to as much as 10 feet below the cellar floors—18 feet or more below street-level—it is only rarely that the post-Roman deposits and structures have outlived the succession of drastic remodellings that has taken place since mediaeval times.

During the Middle Ages, as under the Romans, the processes of accumulation were not as uniform and regular as they were once thought to be. Mediaeval Londoners indeed were faced with problems like those of the Romans in kind but exceeding them in degree. A more densely occupied city, re-created on the shadow of the Roman street-plan, but lacking the guidance of Roman urban administration and order, had to deal with correspondingly enhanced difficulties. To generations habituated to the public services of the twentieth century, sewage and garbage disposal and water-supply are less than mundane matters which loom large only when the arrangements for dealing with them develop a flaw. For mediaeval Londoners, as well as for later generations into the nineteenth century, the problems could be met only by the digging of cesspits, rubbish-pits, wells and water-holes in and about their own property, with or without the benefit of night-soil men and others whose professional task it was to be responsible for their upkeep. The ground of the mediaeval city was therefore honeycombed with pits of various kinds, dug from more than one level and often to considerable depths, and (as already noted) cutting through and destroying the earlier deposits. In addition, the rate of aggradation of the general surface was probably greatly increased in many areas since much material which could not otherwise be disposed of was spread over open ground in gardens and elsewhere, gradually raising the levels. Pits, therefore, and comparatively thick deposits of mixed materials often containing building débris and other rubbish, the one representing a downward movement, the other a process of building-up, are features of the mediaeval deposits of London.

The more tangible remains of buildings are scarcer. In areas which contain modern cellars it is normally found that the whole of the building itself has been swept away. All that survives in such circumstances is some part of the foundations, which are often massive and usually composed of rough chalk blocks with a lavish use of rather poor yellow mortar. These foundations can rarely be fitted into a coherent plan, if only because there is usually no opportunity of extended work covering a large area. There are frequent hints, even in these limited glimpses, that cellars or half-cellars were commonly present in many London buildings. Such features have been seen more completely on the few sites where the absence of modern cellars has preserved the earlier structures up to the level of the modern street.

But cellarless sites are rare in the bombed areas covered by this account: they can certainly be numbered by less than the fingers on two hands. In only one of these cases (below, p. 168) have the remains been sufficient to give a clear impression of the character of the building. The most rewarding mediaeval sites in the city are those which have prolonged their original use into the present day and which therefore may be expected to retain within their existing outlines some part of their mediaeval features. Apart from certain obvious exceptions, no mediaeval secular buildings in the city or its environs have survived the drastic reconstructions of the nineteenth century. It must furthermore be remembered that the Great Fire of 1666 had already cleared much of the city area and prepared it for rebuilding in eighteenth-century brick. Ecclesiastical buildings are another matter: more will be said of them below.

2. THE ‘LOST’ CENTURIES

Here before turning to a summary account of the more significant discoveries relating to post-Roman London something must be said on the problem of the ‘lost’ centuries—the period of a hundred years or so which followed the Roman withdrawal in the early fifth century A.D., and during which, according to a widely accepted view, the city was abandoned.

One of the outstanding negative results of the Excavation Council’s work over more than sixteen years has been the absence of structural, or indeed any other, evidence for the occupation of London in the early part of the Saxon period. A feature of a number of sections has been the way in which finds other than Roman survivals have also been lacking.

Since in 19351 Dr. (now Sir) Mortimer Wheeler listed by their periods the chance finds of Saxon origin from the walled city and its immediate neighbourhood there have been few if any notable additions to the tally of objects falling within the period of the fifth to the eighth centuries. The number of such finds is in any case not a large one; but taken in conjunction with the distribution of churches whose dedications can be ascribed to the same period, their predominance in the area to the west of the Walbrook stream is the basis for the view that it was the western half of the city on which was centred the early Saxon recolonisation of London. Saxon London therefore developed in a direction which reversed that of the Roman occupation, spreading eastwards at a later day to the Cornhill area, which in Roman times had constituted the original bridgehead settlement. This later development, taking place over the ninth to the eleventh centuries A.D., is also illustrated in Wheeler’s maps.

The absence of early Saxon discoveries referred to above is remarkable; for, as has already been noted (p. 15), the western half of the city as the area in which the incidence of bomb-damage was much heavier than anywhere else, has also been the area in which most of the Council’s investigations have taken place. The first clearly defined chronological evidence, such as it is, in this region is consistently of later Saxon date. But again this evidence is not associated with structural remains and is made up almost entirely of scattered sherds of painted ware of the type named after the kilns at Pingsdorf (near Cologne in the Rhineland), though it was not necessarily all produced there.1 This ware ranges in date from the mid-ninth to the late twelfth century.

The evidence from the ground seems to indicate that the absence of early Saxon remains is not due to the later destruction of the levels in which they would have occurred. Continued absence of early Saxon relics seems to corroborate the view that London was indeed largely unoccupied for some time after the collapse of the Roman power in the fifth century. The puzzling feature about this gap in the archaeological evidence is the contradiction that it embodies with the situation in London in the late sixth and early seventh centuries as implied by the records. The ordination of Mellitus as bishop of London in 604 and the building of the church of St. Paul by King Ethelbert must be taken to mark the renewal on some scale of the occupation of London by about A.D. 600.2 This would seem to be true even if this first attempt to establish Christianity in post-Roman London must be accepted as having failed. Yet the archaeological evidence seems to be consistent in showing no sign of life until more than 150 years later. The explanation of this apparent contradiction may be that the area of early Saxon occupation was much less extensive than has been thought. Is it possible that it was indeed limited to the immediate area of the western hill on which King Ethelbert built the first cathedral; and that even the limited expansion which would have carried traces of it to the margins of the hill did not take place until the ninth or tenth century? The hope was entertained that some part of the answer to these questions might be found in the large bombed area of Paternoster Row (26–9) immediately north of St. Paul’s Cathedral; but nothing bearing on the problem was found.

In the meantime, it is in keeping with the evidence of the scattered finds that the first structural remains of buildings should be relatively late in the period covered by the ‘Pingsdorf’ ware already mentioned.

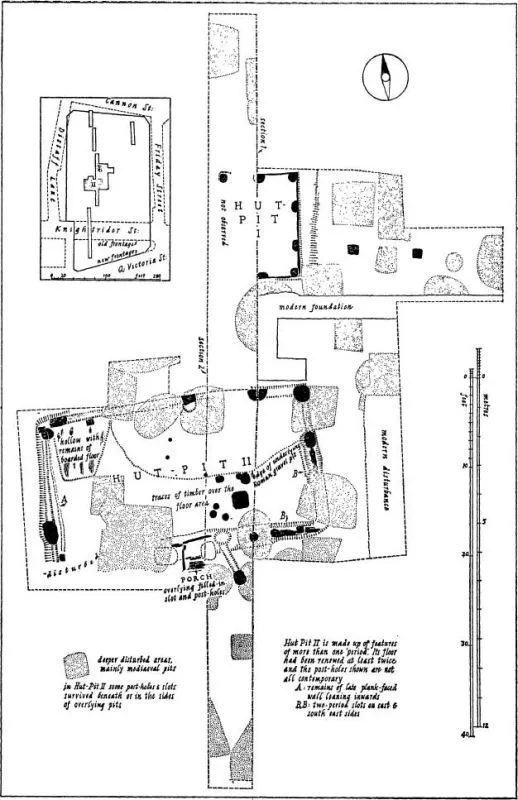

3. HUT-PITS IN CANNON STREET AND ELSEWHERE

The evidence in question was uncovered on the Financial Times site in Cannon Street, about 200 yards south-east of St. Paul’s, in 1955 (35). The fringes of this site to north and south were comparatively unproductive. For some distance back from Cannon Street disturbance of all periods left little Roman material untouched: here a single mediaeval pit was interesting for its well-preserved wicker-work lining (Plate 71: p. 161 below). To the south (Knightrider Street–Queen Victoria Street) the early features had vanished for a different reason. Knightrider Street, now in part eliminated by ‘redevelopment’, lay near the edge of the 50-foot terrace, which here falls fairly sharply to the river-frontage level in Thames Street. The natural contours of the area were drastically modified by the construction of Queen Victoria Street in 1869. Cellars, built no doubt as part of this construction, had been terraced into the slope above the street, with the result that only the natural gravel had survived beneath their floors (p. 145).

In the central part of the site a greater depth of artificial deposits remained. There was no brickearth, possibly because it had been removed in antiquity. The surface of the natural gravel lay 5–6 feet below the cellar floor and was much cut into by pits of various kinds, but the biggest disturbance was an irregular excavation, over 40 feet long as revealed in the cutting, and from 3–5 feet deep below the existing gravel surface. This hollow was filled with mixed deposits deliberately introduced and containing dark occupation material in irregular layers. It is most probably to be explained as a Roman gravel-pit, dug, no doubt, while this area was still outside the built-up extent of London.

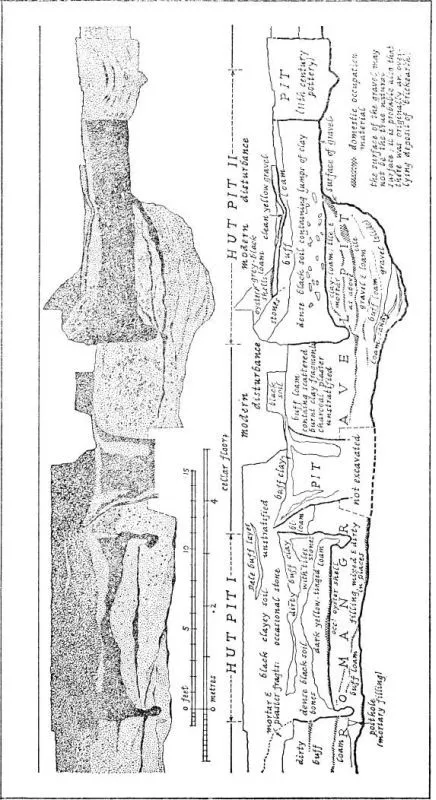

34. Cannon Street (Financial Times site: 35): section across hut-pits.

More important than this, however, were two later cavities, both dug partly into the quarry-filling (

Plate 67). As they presented themselves in the section it was thought that they might be hut-pits and this interpretation was in due course confirmed when the ground on each side of the original cutting was opened up. Of the two pits, that to the north was the smaller (11

feet long), its main axis roughly north-and-south (

Plate 68). By an unfortunate accident its western half was destroyed unrecorded apart from one post-hole, but it must have been about 9 feet wide. The sides of the pit, recognisable to a height of just over 3 feet above its level floor, were practically vertical (section:

Fig. 34). The lower part certainly had been boarded,

the timber surviving as a sharp dense black line. There was an indication on the east side that the pit had been heightened by the addition of a bank of which a small portion remained. In the angles of the pit and at intervals along the sides were massive post-holes which looked as if they had been intended for tree-trunks split in half. Those on the sides in particular were D-shaped in plan, with their straight faces against the wall of the pit, where they had helped to keep the timber lining in place. These post-holes were normally more than a foot across and 15 inches or so deep. There was an uneven layer of unproductive occupation-soil over the hut-floor. Provision for an entrance must have been made on the west side of the pit.

The second pit (32

by 17 feet:

Plate 69) to the south was more complicated in its features, having existed apparently in at least two versions. It had also been much cut up by later pits and by recent cesspits and other structures. Its floor was about 6 feet below the cellar surface and the wall stood to a maximum height of 4 feet above that. Here the arrangement seems to have been that of a gully (or more probably a sleeper-trench) with very large post-holes at 3–4-foot intervals along it (

Fig. 35). As with the first pit, the post-holes were often semi-circular, though less sharply cut, and rather more than a foot in depth. The site was somewhat damp, so that remains of timber had survived in a number of places. There were indications of at least two planked floors, as well as of wall-linings on the west and north sides. The entrance to the hut had clearly been through the middle of the south side. In spite of much destruction by later pits there were indications of a wooden sill or doorway and possibly also of a porch, only the eastern half of which had survived.

35. Cannon Street (Financial Times site: 55): plan of hut-pits.

In this summary account many details have been omitted, but enough has been said to make clear the general character of the structures represented by these remains. They were rectangular huts sunk perhaps to at least half their total height into the ground, their roofs, presumably pitched, supported by remarkably large timber uprights. The immediate and obvious parallel for this combination of elements is provided by the Saxon huts which have become increasingly well known in this country since E. T. Leeds and G. C. Dunning published their discoveries at Sutton Courtenay and Bourton-on-the-Water in 1921–6 and 1931 respectively.1 But while the relationships of the London hut-hollows appear to be clear enough their actual date is less easy to decide, at any rate until the evidence from the site can be subjected to a more detailed examination than it has yet received. From at least one pit which was later than the second hut came pottery which, being of eleventh-century date, shows that the huts had been given up and were at least partly filled by early Norman times. The Financial Times huts must therefore be regarded as of at least late Saxon date, ev...