![]() Part I

Part I![]()

1 Opening paragraphs1

The state (guo2) has six kinds of official duties, and the hundred artisans (baigong3) are under one head.

There are those who sit idly to deliberate upon the Dao,4 and there are others who take action to execute it. Some artisans check external characteristics, such as the curvature and straight, and examine the internal quality (of natural objects)5, prepare the five raw materials (wucai6), and make instruments for people’s livelihood; others trade and circulate things rare and strange from the four corners (of the world), in order to make objects of value. Others again devote their strength to farming to augment the products of the earth. Still others process the silk and hemp and weave clothes from them.

Now it is the king and grand dukes who sit idly to deliberate upon the Dao, while carrying it into execution is the responsibility of ministers and officials. Examining the raw materials and making the practical instruments is the charge of the hundred artisans.7 Trade and circulation are the affairs of merchants and traders; tilling the soil belongs to the farmers, and weaving of silk and hemp is the duty of women workers.8

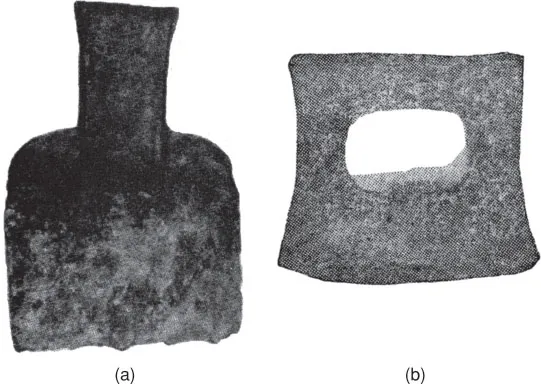

In the state of Yue,9 there are no special craftsmen of hoes (bo10) but every man knows how to make one. In the state of Yan,11 there are no special craftsmen of hide armor (han12) but every man knows how to make it. In the state of Qin,13 there are no special craftsmen of pikestaffs (lu14) but every man knows how to make them. Among the nomads Hu15 there are no special craftsmen of bow and chariot (gong che16) but all the men there are proficient in the art.

It is men of wisdom (zhizhe17) who invent tools and machines. The skillful men (qiaozhe18) maintain their traditions, and those who keep in the same line of occupation generation by generation are called artisans (gong19). All that is done by the hundred artisans are originally the creation of the sages. Smelting metal to make sharp, strong weapons, hardening clay to make vessels, fashioning chariots for going on land, and making boats for crossing water—all these arts are creations of the sages.20

When the seasons (shi21) of heaven are favorable, the qi22 (local influences) of the earth also are favorable, materials have their proper virtues (mei23), and the work of skillful workers is cunning (gong qiao24), then these four being all combined, perfection is attainable. But with suitable material and skilled workmen it still may happen that the product is not satisfactory; in this case, the season has not been propitious, or the favorable qi of the earth has not been successfully obtained. [Heaven has its seasons of production and destruction; trees and grasses have a time to live and a time to die. Even rocks crumble, and water freezes or flows. These are according to the natural seasons of heaven.]25 Take, for instance, the sweet-fruited orange (ju26), when it is transplanted to the north of the Huai27 River, it turns into the bitter-fruited orange (zhi28); the crested mynah (quyu29) could not live across the Ji30 River; and raccoon dogs or badgers (he31) die if they pass over the Wen32 River. This doubtless is from the effects of the qi of the earth. The knives of Zheng,33 the axes of Song,34 the pen-knives of Lu,35 and the double-edged swords of Wu36 and Yue are famous for their origin. In no other places, can one make these things so well. This is natural because of the qi of the earth.

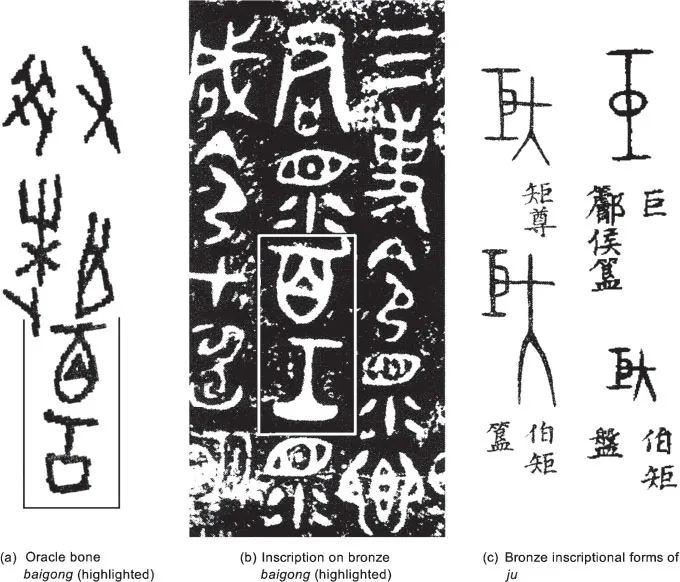

Figure 1.1 Inscriptions of baigong 百工 (the hundred artisans) and ju 矩 (carpenter’s square). (a) Oracle bone baigong of the Shang dynasty. From (detail, ZSKS 1980, 2525 (H65:2)). (b) Inscriptions of baigong on cover of the “Ling fangyi” of the Zhou dynasty. From (detail, Guo Moruo ([1957] 1999, Vol. 1, rubbing 3). (c) Bronze inscriptional forms of ju of the Western Zhou period. From Rong Geng (1985, no. 0731).

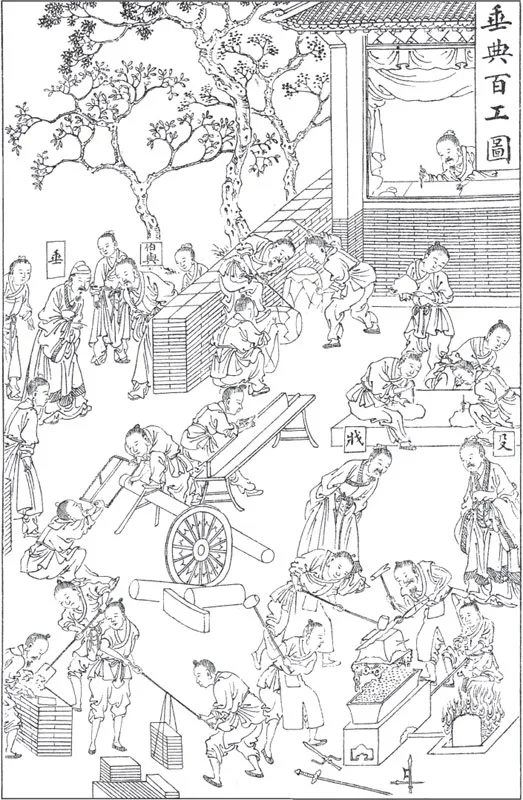

Figure 1.2 A late Qing representation of artisans at work managed by the first director Chui and his assistants. From Sun Jianai et al. (1905, ch. 2, 33a). The caption: Chui 垂 was managing the hundred artisans.

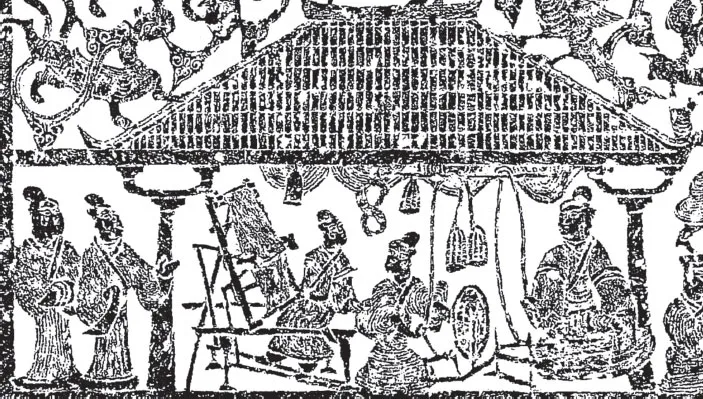

Figure 1.3 A stone relief with scene of people weaving on a treadle-loom at the left, quilling on a quilling-wheel at the center, and throwing of silk thread on a spooling-reel at the right, unearthed in 1956 from the Han grave in Honglou 洪樓 Tongshan 銅山, Jiangsu province. After Ouyang Moyi (2001, 32, Fig. 31), by courtesy of Ouyang Moyi.

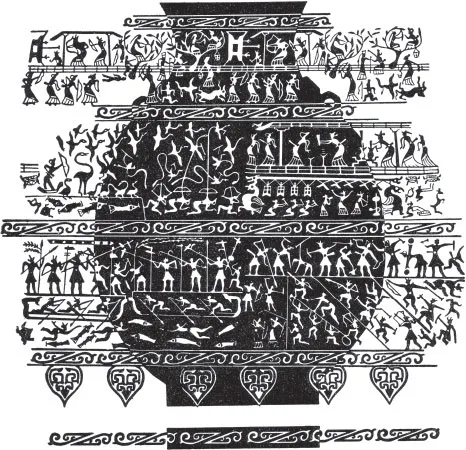

Figure 1.4 Line drawing of the décor on an inlaid bronze vase hu 壺 from the Warring States period, preserved in Shanghai Museum. Depictions show people engaged in such activities as warfare, hunting, boating, rituals, music making, picking of silkworm thorn leaves, bow making, archery, and food preparation. By courtesy of Shanghai Museum.

Figure 1.5 Bronze shovel of the Wu state and bronze hoe of the Yue state. (a) Bronze shovel unearthed in 1972 from a fifth century BCE tomb of Wu in Chengqiao 程橋, Liuhe 六合, Jiangsu province. Length 10.4 cm. Width 7 cm. After Jun Wenren (1988, Fig. 7a). (b) Bronze hoe of Yue. After Jun Wenren (1993, Fig. 1-2b).

Figure 1.6 Rock carving of the bow and carriage in Yin 陰 Mountain, Inner...