![]()

| Background to a Study of the Old Stone Age in Britain | Chapter 1 |

GENERAL INTRODUCTION: THE NATURE OF THE ENQUIRY

It’s a good thing that archaeologists are inclined to be optimists. If some level-headed realist from another discipline were to be confronted with the task of presenting a factual account of what actually happened, in human terms, during the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic periods in the area now known as Britain, would he not decline the task as soon as he had taken stock of the evidence? He would note, for example, that something like a hundred thousand stone artefacts of the period were available to him, but that only a tiny proportion of these had been found in situ – that is to say, in approximately the places where their makers or users left them. He would observe that it is not really possible to assign a date in years to the manufacture of any one of them, knowing on unimpeachable evidence that it is certainly accurate within ten thousand years either way. He would consider the almost total lack of artefacts of perishable materials like wood and bone to offset the abundance of stone, though it is reasonable to suppose by analogy with recent primitive stonetool-using peoples that stone implements would not have been the most numerous material possessions of the British Palaeolithic populations, and in many day-to-day situations would not have been the most important, either. He would take account of the fact that no certain trace of a habitation structure has been properly recorded from any British Lower or Middle Palaeolithic site – a situation that can be contrasted with the rather fleeting British Mesolithic period, let alone with the remainder of British prehistory which is documented by a rich variety of field monuments including domestic, defensive, ceremonial and sacred sites. And, as regards the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic population itself, the human beings with whom he is seeking to make historical contact, they are represented by about enough fragments of skeletal material in all to fill a medium-sized paper bag. Even those survive by pure chance; deliberate burial of the dead does begin in the Middle Palaeolithic, but no British example is known.

In parallel to these grave shortcomings of the archaeological evidence, the British Pleistocene sequence, which should ideally provide not merely the evidence for the succession of natural backgrounds to human activity in Britain during the Palaeolithic period, but also a finely calibrated time-scale, presents major interpretive problems of its own in many parts of the country. The highly important matter of establishing both archaeological and geological correlations between Britain and adjacent areas of Continental Europe, let alone further afield, is again notoriously difficult.

One way and another, then, the meandering byways and infrequent highways of the British Lower and Middle Palaeolithic certainly seem to have been laid out with the optimist in mind, and our level-headed realist might well feel inclined to advise his readers to go straight to the science-fiction shelves instead while he directed his efforts as an archaeological author into some period not older than the spread of early agriculture. Would he do that? If he is really worthy of the title assigned to him here, he ought actually to conclude that he is needed as never before in his academic life: it requires an optimist to undertake this task, but a realist to carry it out successfully. When the evidence is in such a sad state, tentative or even firm conclusions may still be perfectly possible, but a careful watch must be kept upon them. The present writer gladly aspires to the title of optimist in this and everything else; his attainment as a realist must remain for the reader to judge.

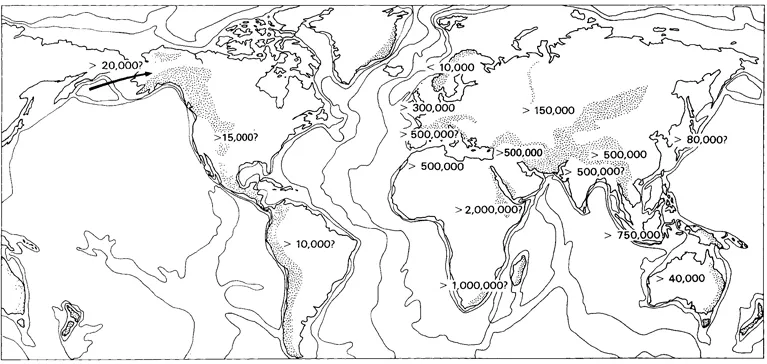

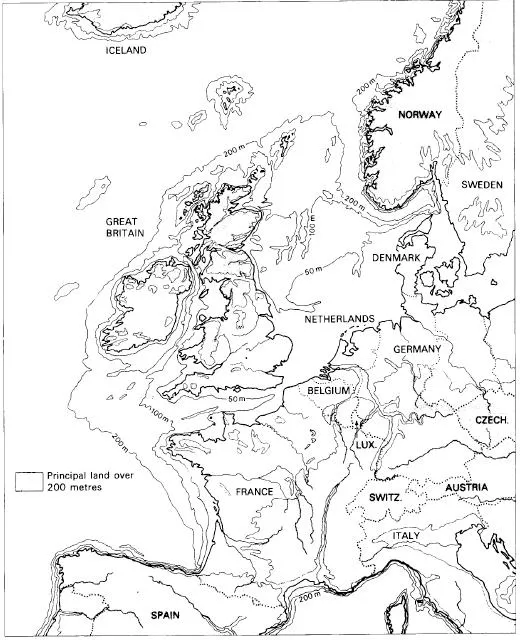

The fact is clear enough, that there was human occupation in Britain during the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic periods over at least a quarter of a million years, and perhaps nearly twice as long, though probably not continuously. That is to say, the period with which we are here concerned is fifty or even a hundred times the length of the time which has elapsed between the start of the British Neolithic, remote as that may seem, and the present day. Inevitably, much that was vital to human physical and cultural development took place during that long span, and every item of information that can be salvaged from so remote a period is of value. Small wonder if we discern the events of that time somewhat hazily, for in searching for evidence of them we enter a world utterly different from the one we know. The name Britain becomes meaningless: we are concerned with a small area of land which lay right at the north-west extremity of the world so far as early Palaeolithic man knew it (Fig. 1:1). Sometimes it was a peninsula of the main land-mass, substantial tracts of what are now the southern North Sea and the English Channel being dry land; at other times it was an island (Fig. 1:2). Sometimes ice-sheets covered most of the land, and periglacial conditions gripped the rest; at other times animals and plants which we should not today seek outside the mediterranean or sub-tropical climatic zones of the world could thrive as far north as the English Midlands and occasionally further. Some areas of Britain were also as different from the present in their relief and drainage patterns as they were in their fauna and flora.

As regards man himself, it is not merely a question of shedding modern attitudes and the accumulated experience of the whole historic and later prehistoric periods, but, for the earlier Palaeolithic stages at least, even of trying to penetrate the physical and psychological make-up and properties of men of other species, all now extinct, within the genus Homo. All living men today belong to the same sub-species, Homo sapiens sapiens, and differences of race and colour, not to mention creed, are genuinely superficial: it is simply not possible to go elsewhere in the world and observe men of other sub-species, let alone species, in the way that one can go out and study, say, processes of erosion or deposition under glacial conditions. This then must be a real barrier to knowledge and one would suppose it to be an increasingly serious one the further back in time one goes: neither primate behaviour studies nor the ethnography of modern primitive peoples can provide complete answers.

It is then surely fair to say that there is a bigger gap of comprehension, as well as of time, between the prehistorian and his archaeological objectives in the earlier Palaeolithic than there is between his colleagues and the archaeology of whatever other period they may be studying. It is also true that in Britain the Palaeolithic material has been subjected to far greater disturbance and destruction than that belonging to more recent periods. This is not merely a matter of passing time: when one considers the destructive power of the forces at work in the glaciation and deglaciation of northern and midland Britain, and even in the more southerly periglacial zone (forces which in many parts were unleashed on several separate occasions), then it seems remarkable that anything has survived at all. As we have already noted, a great deal that would have been immensely informative has not been preserved. This is the main reason why so much of this book has to do with stone implements, because they have a very high survival capacity. It is an interesting and perhaps sobering reflection, in passing, that when the great ice sheets extend again, as there is every reason to suppose they eventually will, the Lower Palaeolithic stone handaxes, cores and flakes, stored in their thousands in the dusty basements of our museums, will come through it, all over again, with much less damage than the beautiful and sophisticated artefacts on show in the galleries upstairs where they have been placed to represent the summit of artistic or technological achievement in the various stages of our own culture. And how will subsequent archaeologists judge us then? By other peoples’ handaxes, redeposited in glaci-fluvial or fluviatile gravels? If so, a certain amount of rough justice may well be done.

1:1 World map, with some conservative estimates for the earliest occupation of important areas. Note the position of Britain at the north-western edge of Lower Palaeolithic settlement

1:2 Britain in relation to the north-west of Continental Europe. The modern marine contours give some idea of the shape of a former ‘British peninsula’

If the preceding paragraphs have stressed the difficulties attendant on a study of the British Lower and Middle Palaeolithic, it has not been the author’s intention to put the reader off the subject altogether so much as to warn him, if he is perhaps used to the study of more recent periods, that he may find the conclusions reached in this book few in number, imprecise and tentative in quality, and resting on evidence that is often painfully weak. Only rarely can cause and effect, and the more dynamic aspects of human existence, be brought into sharp focus. This is certainly no green pasture for the New Archaeologists (as they used to be called): they must either tread the steep and rugged pathway rejoicingly, as some may care to do, to the subject’s profit, or go elsewhere muttering about low-density evidential catchment situations inevitably productive of low-resolution culture-historical syntheses poorly time-calibrated. Indeed, it is not merely legitimate but quite essential when examining the British Palaeolithic material, to keep an eye firmly on other parts of the world, where sometimes the evidence for similar situations is altogether better preserved: missing data can on occasion be fairly borrowed from elsewhere. But there is another compelling reason for proceeding in this way. It has already been observed that Britain lay at the extreme edge of the Palaeolithic world, and was subject to marked fluctuations of climate and temperature. It follows from this that Britain is essentially an area to which human groups came intermittently when conditions were favourable, rather than one which they occupied permanently. So, from the outset, we can hardly expect to find in the British Palaeolithic continuous ‘cultural evolution’ so much as a discontinuous record of changes for which the explanations may often lie elsewhere. On the other hand, at times when the peninsula became an island, it would clearly be possible for human groups in Britain to become isolated from external influences and to develop along their own lines for a while. For all these reasons it is important that the British Palaeolithic should be studied in its proper context rather than on its own, and its immediate context is western Continental Europe, especially France and the western end of the North European plain.

SCOPE OF THE ENQUIRY: A PREVIEW

The formal limits of the period with which this book is concerned can be stated quite simply, at the cost of delving briefly into the history of archaeology.1 The name ‘Palaeolithic’ implies ‘Old Stone’ Age and is a nineteenth-century off-shoot of the original Three Age System defined and pioneered by C.J. Thomsen, J.J.A. Worsaae and several others (Daniel 1962, 1967, 1975). This division of the prehistoric period into a Stone Age, followed by a Bronze Age, followed by an Iron Age, was a theoretical step of no small importance which occurred early in the nineteenth century, and over 150 years later it still retains a strong hold on the more popular section of the archaeological literature (cf. Roe 1970). Such terminology is however wholly out of keeping with the spirit of current research, much of which is directed towards elucidating the totality of any human group’s existence, including the intricate relationships between it and all the diverse elements of the contemporary natural background;it is scarcely appropriate therefore to name major periods of prehistory after raw materials which were exploited by some human groups in certain areas for making a small proportion of their customary artefacts. But one can’t get rid of the Three Ages terminology just like that, for whatever good reasons: the various names have by now become shorthand labels whose use generally implies a whole mass of technological, economic and social information, without actually spelling it out.

Even by the middle of the nineteenth century ‘Stone Age’ had been found too restricted a term to cope adequately with all the different kinds of archaeological material that could be seen to precede the first occurrences of metal artefacts, and so it became divided first into the ‘Age of Chipped Stone’ followed by the ‘Age of Polished Stone’, with ‘Old Stone Age’ and ‘New Stone Age’ or the Greek-derived ‘Palaeolithic’ and ‘Neolithic’ coming in later as alternatives. In due course a ‘Mesolithic’ (Middle Stone Age) or ‘Age of Pygmy Flints’ was found to be necessary as well, interposed between the other two. These names clearly reflect various attitudes of the times. Fine implements were collected and studied individually for their own sake, from the points of view of typology and technology; what one observed in one’s own area would doubtless be the case in other lands, so that the ‘ages’ were regarded as being of general validity; age succeeded age by a kind of evolutionary process. With luck there might be strati-graphic evidence to demonstrate the order in which the different kinds of stone tool occurred through time, but it did not greatly matter, since one had only to decide their evolutionary status to place them in their correct sequence.

These broad subdivisions of the Stone Age naturally attracted their own specialists amongst the collector-antiquaries, and gradually each became known in greater detail, the new information being accommodated by further subdivision. The Palaeolithic was seen to begin with a Drift Period or Age of Drift Implements, which was followed by a Cave Period: that is to say, it was reckoned, and in due course demonstrated, that the implements which could be found deep in the gravel deposits of river valleys like those of the Thames and the Somme, were older than those which occurred in the fillings of the caves in south-west France, or in Belgium or elsewhere. Were not their typology and the technology of their manufacture far cruder? To be fair, there was other evidence too, of a more reliable kind, notably the different faunal assemblages accompanying the artefacts – some chronological schemes of the period used designations like ‘Reindeer Age’ or ‘Age of the Mammoth’. As the pace of discovery quickened over the second half of the nineteenth century, the Cave Period had to be divided again, because it was clear that in an ideal sequence the lower levels would produce artefacts more like those of the Drift Period, though better made and including some new types, while the upper levels yielded finely made tools worked on narrow blade-like flakes, accompanied by frequent artefacts of bone and antler, many of which were beautifully decorated. Different human types, too, were associated with these two parts of the Cave Period – the suitably more primitive-looking Neanderthal man with the earlier, and essentially modern types with the later.

Thus, by the late nineteenth century, there already existed a three-fold division within the Old Stone Age, which forms the basis of Lower, Middle and Upper Palaeolithic as we know them, much refined, today. By then it had also become customary to distinguish cultural periods and call them after type-sites (the sites where material belonging to each was first found): the majority of the names were French, since most of the relevant early work was done in France. The main culture names for the Drift Period were Acheulian and Chellean, called after Saint-Acheul and Chelles in the Somme Valley, though others were also used. The older division of the Cave period became Mousterian, or the Age of Le Moustier, after the abri supérieur at Le Moustier in the Dordogne, while the principal subdivisions of the later Cave Period at this time were Aurignacian, after Aurignac (Haute-Garonne), Solutrean after Le Roc de Solutré (Saône et Loire) and Magdalenian after the shelter of La Madeleine, near Cursac, Dordogne. Most of these terms remain in use today, although their precise meaning has altered somewhat in some cases.

In the archaic terminology of the foregoing, therefore, this book is concerned with the representation in Britain of the Drift Period and the earlier division of the Cave Period, and use can reasonably be made of the names Acheulian and Mousterian, out of those mentioned above. In more modern language, but still for the moment in terms of material culture, we are considering the period from the earliest appearance of man-made tools in Britain, down to the almost explosive spread of distinctive Upper Palaeolithic technology, which took place over most of Europe, in parts of North Africa, and in parts of Asia, notably South-West Asia and certain areas of the USSR; between about 45,000 and 30,000 years ago.

In human terms, the period to be studied ends at the spread of Homo sapiens sapiens to Western Europe, he being traditionally regarded as the bearer of the Upper Palaeolithic cultures and indeed of all those which followed, including our own, though whether the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic and the first appearance of Homo sapiens sapiens always coincide exactly in every area is becoming increasingly open to doubt. Some Middle Palaeolithic populations may have crossed a technological frontier before the new human type reached their area; this is a point of great interest, but regrettably it is not one on which the British evidence can cast any useful light at present. As regards what earlier human types2 we are actually concerned with in Britain, much doubt must remain until new fossil hominid finds are made (Fig. 1:3). The only substantial British discovery has been the fragments of the famous Swanscombe skull (Plate 14), classified as belonging to Homo sapiens — that is, to an early form of our own species apparently ancestral both to our own subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens, and also to the extinct Neanderthal Man, who is properly called Homo sapiens neanderthalensis. In so far as there is a small amount of classic Mousterian archaeological material present in Britain, it may seem safe enough to suppose that Neanderthal man too was here for a while, since, so far as Wester...