eBook - ePub

Bone, Antler, Ivory and Horn

The Technology of Skeletal Materials Since the Roman Period

- 254 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bone, Antler, Ivory and Horn

The Technology of Skeletal Materials Since the Roman Period

About this book

Artefacts made from skeletal materials since the Roman period were, before this book, neglected as a serious area of study. This is a comprehensive account which reviews over fifty categories of artefact. The book starts with a consideration of the formation, morphology and mechanical properties of the materials and illuminates characteristics concerning working with them. Following chapters discuss the organisation of the industry and trade in such items, including the changing status of the industry over time. Archaeological evidence is combined with that from historical and ethnological sources, with many illustrations providing key visual reference. Originally published in 1985.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bone, Antler, Ivory and Horn by Arthur MacGregor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Raw Materials

The element of objectivity gained by examination of each of the raw materials considered here is a necessary prerequisite for the proper study of the artefacts which were made from them. In some instances their distinguishing characteristics came to be acutely appreciated by those who utilised them, both as the result of personal observation and of generations of inherited knowledge. This was the manner in which any craftsman learned his trade in the days before a theoretical grounding was added to the otherwise practical curriculum of the trainee technician. By the time he had finished his apprenticeship, such a craftsman would have acquired a ‘feel’ for his materials based on the experience he had gained for himself and had absorbed from his masters: he might well find difficulty in expressing precisely why one piece of raw material was particularly suitable for one purpose or another, but his judgement would be no less valid and accurate for all that. In our attempts to reconstruct the factors which led to the evolution of particular craft practices in antiquity we are, in the case of skeletal materials, denied access to any body of accumulated knowledge, since nearly all use of these materials ceased long ago and written records relating to them are few. Instead we must substitute scientifically-obtained data through which objective valuations can be made and from which we can attempt to infer the qualities which led to the consistent adoption of specific materials for specific purposes.

The overall picture which emerges from this exercise places skeletal materials in a new light: whereas there has in the past been a tendency to regard bone, antler and horn as inferior substitutes for metal or even ivory, the respective mechanical properties which each of these possesses are in many ways truly remarkable, and often render them supremely suitable for particular tasks.

A further important consideration is the manner in which the gross characteristics of particular materials, especially whole bones, directly conditioned the evolution of typologies. In the past these typologies have all too often been studied with no reference whatever to such factors, but in many cases it can be shown that the morphology of the raw materials had a crucial influence and, in some instances, even led to the conditioning of forms subsequently executed in other materials in which these primary controls were absent.

An initial problem encountered in this study is one of suitable terminology. Osseous skeletons, while consisting of many diverse components, are structurally distinct from teeth; neither of these in turn has anything in common with the keratinous material of which horns are composed. In an attempt to produce an appropriate portmanteau word which would encompass all animal substances used in the production of tools and implements, the term ‘osteodontokeratic materials’ has been adopted by some archaeologists (e.g. Dart 1957) while Halstead (1974) has settled for the more prosaic ‘vertebrate hard tissues’. While each of these alternatives possesses a higher degree of biological precision than that adopted here, the term ‘skeletal materials’ is preferred, as it conveys to the non-specialist a more comprehensible (if strictly less accurate) impression of the scope of this enquiry.

Since a good deal of emphasis is to be laid here on the conditioning exerted on the evolution of artefacts by the raw materials from which each of them was formed, it will be necessary to begin with an account of each category of material in turn; in this way, the nature of each can be assessed, mutual comparisons can be made, a working terminology established and the characteristics by which each can be identified made known.

Bone

The archaeologist with an interest in bones is already well served by a number of publications, among which those of Brothwell (1972), Chaplin (1971), Cornwall (1974), Ryder (1968a) and Schmid (1972) deserve particular mention. In each of these works, however, particular emphasis is placed on the morphology of bones, the problems of identifying them and their distribution and function within the living skeleton. Although these factors are of some importance in the present context, they are secondary to the main theme. As the materials reviewed here are considered outside the environment for which they were originally evolved, their fitness for their original function is not of direct importance, although the qualities which recommend them for utilisation in a particular way are often interconnected with their original skeletal function.

Formation

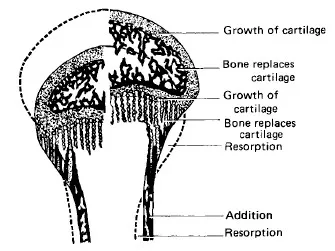

According to the manner in which it develops at the foetal stage, a broad distinction is drawn between membrane (or dermal) bone, which originates in fibrous membrane, and cartilage bone, whose origins lie in pre-existing foetal cartilage. Both types develop through a process of ossification, in which soft tissue is progressively replaced by bone through the action of specialised osteoblast (bone-producing) cells, although details of the process differ for the two varieties. Ossification continues after birth at the growing zones until the definitive size is reached. Cartilage bones are formed by gradual replacement with bone tissue of embryonic cartilage models. They are extended (Figure 1) by progressive ossification of the proliferating epiphyseal cartilage which separates the dia-physis or shaft from the articular ends or epiphyses (endochondral ossification), the process being completed with maturity. In the case of membrane bones growth takes place around the peripheries (intra-membraneous ossification), the junctions or sutures between certain bones again becoming fused in maturity (Freeman and Bracegirdle 1967; Ham 1965; Weinmann and Sicher 1955).

Figure 1: Extension of long-bones by endochondral ossification (after Ham). While new cartilage is added to and ossified at the growing ends, a complimentary process of resorption maintains the original form of the bone

The distinction here is therefore between the types of tissue being replaced by the developing bone: the resulting bones are indistinguishable except perhaps for some difference in the coarseness of the initial fibres (Pritchard 1972), and this primary tissue is in any case quickly replaced under normal processes (p. 7). Further evidence for the close links existing between the two types of bone lies in the fact that elements of both types are involved in the development of some bones: the clavicle and mandible, for example, are classified among the membrane bones, even though a large proportion of each has its origin in cartilage, while the long bones, which are counted among the cartilage bones, have much of their shafts formed in membrane (Pritchard 1956).

An important bone-forming membrane, the periosteum, sheathes the external surfaces, while the interior cavities of certain cartilage bones are lined with a corresponding membrane, the endosteum. In addition to its normal osteogenic functions during growth, the periosteum may be stimulated to produce new bone in order to repair damage, or in response to demands from the muscles or tendons for more secure anchorages (McLean and Urist 1961; Ham 1965).1

Structure

Bone tissue consists of an organic and an inorganic fraction, intimately combined. The organic matrix accounts for a considerable part of the weight (variously estimated at between 25 per cent and 60 per cent of the total) and volume (between 40 per cent and 60 per cent of the total) of adult bone (Frost 1967; Sissons 1953; Wainwright et al. 1976). It consists of about 95 per cent of the fibrous protein collagen (which is also a major constituent of tendon and skin), along with other forms of proteins and polysaccharide complexes. Typical collagen has a structure of rope-like fibrils arranged in close proximity to one another and frequently interlinked (Currey 1970a), forming a basic scaffolding for the bone structure.

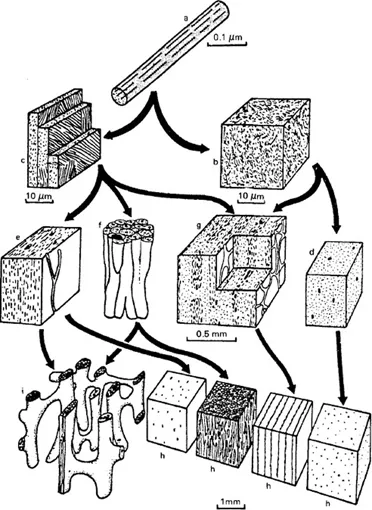

Figure 2: Structure of mammalian bone at different levels of organisation (after Currey) (The arrows indicate which types may contribute to higher levels of structure.)

Key

a Collagen fibril with associated mineral crystals.

b Woven bone. The collagen fibrils are arranged in random fashion.

c Lamellar bone. There are separate lamellae, and the collagen fibrils are arranged in domains of preferred orientation in each lamella.

d Woven bone. Blood channels are shown as large black spots. At this level woven bone is shown by light stippling.

e Primary lamellar bone. Lamellae are indicated by light dashes.

f Haversian bone. A collection of Haversian systems, each with concentric lamellae around a central blood channel.

g Laminar bone. Two blood channel networks are exposed. Note how layers of woven and lamellar bone alternate.

h Compact bone, of the types shown at lower levels.

i Cancellous bone.

In the natural process of ossification, mineral crystals — generally agreed to be hydroxy-apatite, a complex of tricalcium phosphate and calcium hydroxide — surround the collagen fibres.2 There is some dispute (summarised in Wainwright et al. 1976) concerning the shape of these apatite crystals: the commonly-held opinion is that they have the form of needles, but some authorities have claimed that these are in reality plates viewed end on. Whatever their form, the apatite crystals, which are aligned with and bonded to the collagen fibrils, are distinguishable only with high-resolution equipment, their thickness being in the order of 4nm, so that they are quite invisible under the conventional optical microscope. A certain amount of amorphous (non-crystalline) apatite is also present in the inorganic fraction.

With these basic ingredients organi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1. Raw Materials

- 2. Bone and Antler as Materials

- 3. Availability

- 4. Handicraft or Industry?

- 5. Working Methods and Tools

- 6. Artefacts of Skeletal Materials: A Typological Review

- Bibliography

- Index