- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

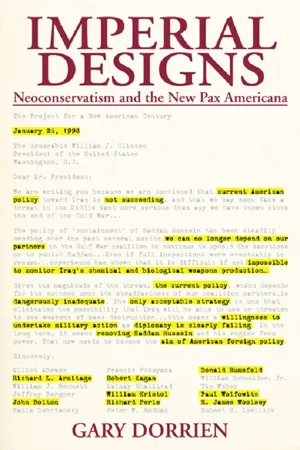

This work argues that the influence of neoconservatives has been none too small and all too important in the shaping of this monumental doctrine and historic moment in American foreign policy. Through a fascinating account of the central figures in the neoconservative movement and their push for war with Iraq, he reveals the imperial designs that have guided them in their quest for the establishment of a global Pax Americana.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Imperial Designs by Gary Dorrien in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

“Trotsky’s Orplians”

A Brief History of Neoconservatism

In the early 1970s the American socialist leader Michael Harrington and his friends at Dissent magazine hung the label “neoconservative” on a group of former allies as an act of dissociation. Many of these former allies had until recently been Harrington’s comrades in the Socialist Party; others were old liberals (some of them former socialists) who disliked what liberalism had become since the mid-1960s. The former group included veteran Cold War socialists Arnold Beichman, Sidney Hook, Emanuel Muravchik, Arch Puddington, John Roche, and Max Shachtman; the latter group included political figures and intellectuals such as Daniel Bell, Nathan Glazer, Henry Jackson, Max Kampelman, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Irving Kristol, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and Ben Wattenberg. A few refugees from the new left, notably Richard John Neuhaus, Michael Novak, and Norman Podhoretz, also migrated to the “neoconservative” camp, as did politically homeless conservatives such as Peter Berger and James Q.Wilson.1

Most of the original neocons supported America’s war in Vietnam, but more important, all were repulsed by America’s antiwar movement. To them it was appalling that the party of Harry Truman and John Kennedy nominated George McGovern for president in 1972. They despaired over the ascension of antiwar activism, feminism, and moralistic idealism in the Democratic Party, which they called “McGovernism.” McGovernism stood for appeasement and the politics of liberal guilt, whereas the neocons stood for a self-confident and militantly interventionist Americanism. The neocons were deeply alienated from what they called the “liberal intelligentsia” and the “fashionable liberal elite.” To them, good liberalism was expansionist, nationalistic, and fiercely anticommunist; it prized patriotic values that were sneered at by the liberal elite. Most of the neocons contended that they had not changed, at least not on the important things. They were not the ones that needed to be renamed. It was Harrington, Irving Howe, Lewis Coser, and others in the orbit of Dissent magazine who had changed, selling out the cause of socialist anticommunism. Worse yet, Harrington’s group had done it to win over the children of the 1960s, who had turned liberalism into a politics of guilt-breeding, anti-interventionist, anti-American idealism.

Harrington and his friends sought to make clear that a parting of ways had occurred. They were no longer associated with the neoconservatives. In the wake of McGovern’s crushing electoral defeat the Socialist Party had imploded, the old left launched a new organization called Social Democrats U.S.A., Harrington formed a new organization called the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee, and the Cold War liberals founded the Coalition for a Democratic Majority to take back the Democratic Party from McGovernism. Harrington wanted to convert the McGovern liberals to democratic socialism. Ten years earlier his emotional and ideological ties to old left anticommunism had alienated the youthful leaders of the new left; now he envisioned a party-realigning coalition of baby boom liberals and progressive social democrats.

But first he had to excommunicate his rightward-moving former comrades from the left, partly to establish his separation from them. By calling them “neoconservatives,” he implied that the old social democrats were not the right wing of the left but the left wing of the right. The difference was crucial, as the labeled party keenly understood. The neocons disputed their label and its insinuations, protesting that they had nothing in common with American conservatives. Many of them didn’t know any conservatives personally. To them, conservatives were country clubbers, reactionaries, racists, and Republicans, nothing like mainstream Democrats or tough social democrats.

The neocons lacked conservative nostalgia. They did not yearn for medieval Christendom, Tory England, the Old South, or laissez-faire capitalism. They were modernists, longtime supporters of the Civil Rights movement, comfortable with a minimal welfare state, and many were trained in the social sciences. Most of them were New York Jews who shuddered at the anti-Semitism and xenophobia of the old right. They may have voted for Richard Nixon but only because the Democratic Party had lost its bearings and the Socialists had stopped running presidential candidates. Calling them conservatives of any kind was insulting.

But the name stuck because they were changing more than they acknowledged. Although they had no conservative friends at the outset of their political transformation, the neocons went on to objectively align themselves with the political right. From the beginning they hated the anti-interventionist and cultural liberationist aspects of the new liberalism, and increasingly they added that liberal economics was wrong, too. Irving Kristol’s The Public Interest led the way on socioeconomic issues, showing the unintended consequences of progressive taxes and government antipoverty programs. The new liberalism, like the old, thought too highly of equality, he argued. Liberal economics penalized achievers, prevented wealth creation, and created a bloated welfare state. The enemy wasn’t merely a youthful overreaction to Vietnam, for the egalitarian illusions of the old liberalism paved the way to the disastrous new liberalism. The Civil Rights movement gave way to “affirmative discrimination” and Black Power nationalism; Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty mostly benefitted a “new class” of parasitic bureaucrats and social workers; the emancipatory rhetoric of liberalism invited new assaults on the social order such as feminism, environmentalism, and gay rights; and America was losing the fight against communism.

Kristol and, later, Michael Novak explained that liberalism catered to the self-promoting idealism of a new generational power bloc, the “new class” children of the 19608 who swelled the ranks of America’s nonproducing managerial class. In the name of compassion, liberals created new government programs, but the chief effect of the programs was to service the career ambitions of new class baby boomers. Modern liberalism wanted America to be weak but government to be strong. With a polemical style and vocabulary that betrayed their backgrounds in the left, the neocons skewered the new class for its appeasing antimilitarism and devotion to expanded government engineering.2

In the mid-1970s the neocons tried to retake the Democratic Party but their presidential candidate, Henry “Scoop” Jackson, was soundly defeated in the primaries, and by then some neocons were well to the right of Jackson on economic policy. Tellingly, the first neoconservative to accept Harrington’s label, Irving Kristol, was also the first to join the Republican Party, in the early 1970s; later he moved all the way to supply-side economics. While Kristol’s colleagues at the Public Interest bristled at their consignment to the political right, Kristol acknowledged that he had become some kind of conservative. Having renounced his hothouse socialist background before most of his friends, Kristol had more emotional distance from the left than they did, which made it easier to acknowledge that he was drifting toward some kind of conservatism. His affinity for neo-orthodox theology helped him accept the term neoconservative.

Some neocons held on to their social democratic values after Kristol and Michael Novak made neoconservatism an emphatically capitalist ideology. Others such as Bell and Moynihan distanced themselves from neoconservatism after it became an overwhelmingly Republican movement. The key to the movement’s Republican turn, however, was foreign policy. The neocons failed to purge the Democratic Party of McGovernism, and in 1976 they ruefully witnessed the triumph of a moderate Southern moralist who shared none of their foreign policy agenda. They warned Jimmy Carter that the Soviets were winning the Cold War; he replied by appointing none of them to high-ranking positions in his administration. The neocons turned on him furiously, making “Carterism” an epithet ranking with McGovernism. Prominent neoconservative and Commentary editor Norman Podhoretz led the charge against the Democratic president. Less than a year after Carter took office, Podhoretz scolded that the same liberals who had run the Vietnam War under Kennedy and Johnson were atoning for their sins by keeping America at home. He noted that Carter had recently congratulated himself and his fellow Americans for overcoming their “inordinate fear of communism.” To Podhoretz, this declaration epitomized the stupidity and corruption of spirit that characterized America’s “culture of appeasement.” America was surrendering to Soviet power throughout the world because American leaders secretly feared it.3

This reading of the American condition had little place in the Democratic Party, but it perfectly suited Ronald Reagan, who replaced Scoop Jackson as the political hero and rainmaker of the neoconservatives. By 1980 they were happy to call themselves neoconservatives. The term legitimized their place in the Republican Party while distinguishing the neocons from forms of conservatism that were less urbane, ethnic, and ideological than themselves. Neocons Elliott Abrams, Kenneth Adelman, William Bennett, Linda Chavez, Chester Finn, Robert Kagan, Max Kampelman, Jeane Kirkpatrick, William Kristol, Richard Perle, Richard Pipes, Eugene Rostow, and Paul Wolfowitz won high-ranking positions in the Reagan administration; The New Republic half-seriously warned that “Trotsky’s orphans” were taking over the government.4 Neoconservatives provided the intellectual ballast for Reagan’s military buildup and his anticommunist foreign policy, especially his maneuvers in Central America. While disagreeing with each other over how much should be done with America’s enhanced firepower, they agreed that a massive military buildup was necessary and that America needed to “take the fight to the Soviets.”

They were the last true believers in the efficacy of Soviet totalitarianism. In the mid-1980s, most neoconservatives brushed aside any suggestion that the Soviet economy was disintegrating, or that dissident movements in the Soviet bloc were revealing cracks in the Soviet empire, or that Gorbachev’s reforms should be taken seriously. For them, the absolute domestic power of the Communist Party and the communist duty to create a communist world order precluded the possibility of genuine change anywhere in the Soviet bloc. Neocons such as Podhoretz, Frank Gaffney, and Michael Ledeen outflanked Reagan to the right on fighting communism. In the early years of Reagan’s presidency Podhoretz bitterly complained that Reagan, despite his militant rhetoric, skyrocketing military expenditures, and appointment of neoconservatives, capitulated to the Soviets in the struggle for the world.5 In the later years of Reagan’s presidency, Podhoretz bitterly judged that Reagan betrayed the cause of anticommunism.

The neocons warned repeatedly that the United States was in grave danger. America was surrendering unnecessarily to the Soviet enemy in the name of realism and peace. Foreign policy realists such as George Kennan, Stephen Cohen, and Jerry Hough lifted geopolitics, material interests, and mutual security above America s ideological war with the Soviet Union, portraying the Soviet Union as a competing superpower wracked by internal problems. To them, the Soviet Union was a greatpower foe with which the United States could negotiate accommodations on specific issues.6 The neocons replied that these factors were trivial compared to the Cold War struggle for the world. To portray the Soviet Union as a competing superpower was to undermine America’s will and capacity to fight communism. It was the tragic legacy of the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations to have undermined America’s life or death mission. What was needed was a courageously ideological leader who recognized the implacable hostility of the Soviet state and faced up to the necessity of making life intolerable for it. Neocon policy makers Kenneth Adelman, Max Kampelman, Richard Perle, Richard Pipes, and Eugene Rostow made the case for huge increases in military spending, while Perle fashioned Reagan’s peculiar combination of beliefs into the “zero option” for disarmament; neocon intellectual and U.N. ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick defended America’s practice of supporting rightwing dictatorships as bulwarks against communism; outside the administration, Podhoretz warned that the struggle for the world was being lost.7

Neocons invoked the doctrine of totalitarianism as an article of faith. It taught that the Soviet system had immense competitive advantages over democracies by virtue of not being a democracy and that Soviet power was invulnerable to internal challenges. The Soviet state was a fearsome monolith that surpassed the United States in military power and threatened to win the struggle for the world. Repeatedly, Commentary magazine blasted the “culture of appeasement” that appealed for a nuclear freeze and refused to fight communism in Central America. Podhoretz heaped special scorn on antiwar church leaders, homosexual pacifists, and liberal politicians; he also attacked big business appeasers who wanted to do business with the Soviets, complaining that Reagan was too solicitous of the capitalist class to fight the Soviet Union. In his rendering, liberal church leaders and politicians were cowardly moralists and fools, homosexuals opposed war out of their lust for “helpless, good-looking boys,” and the capitalist class perversely sold Soviet leaders the rope that would be used to hang America.8

Podhoretz charged that the new peace activists were motivated by fear, which made them more loathsome than the fellow traveling dupes of an earlier generation who actually liked the Soviet Union, or at least their fantasy of it. The new pacifists felt no attraction to the Soviet Union, he explained; they were simply terrified of it and lacked the courage to resist it. The new movements for nuclear arms control and disarmament were fueled by the cowardly fear that the evils of war always outweighed the worth of any objective for which a war might be fought. But sadly, even Reagan had no stomach for actually fighting communism; his few invasions were tiny and inconsequential; and thus, everywhere he was losing the Cold War.

Podhoretz’s disappointment in Reagan turned to outright contempt during Reagan’s second term. In 1985 he complained that Reagan was repeating the worst mistakes of his predecessors. Reagan’s emerging arms control agreement was a throwback to the Basic Principles of Detente of 1972; his approach to Central America resembled the ill-fated resolution of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis; his approach to Nicaragua, in particular, recycled the disastrous 1962 Declaration on the Neutrality of Laos, which called for the withdrawal of all foreign troops from the area. A truly anticommunist president would have crushed the Nicaraguan Sandinistas and Salvadoran guerrillas; Reagan played political games with them. Podhoretz warned that if Reagan continued down this road in his second term, he would cruelly disappoint those who had believed in his commitment to fight communism.9

The titles of Podhoretz’s articles told the story of his bitter disappointment during Reagan’s second term: “Reagan: A Case of Mistaken Identity,” “How Reagan Succeeds as a Carter Clone,” and, most plaintively, “What If Reagan Were President?” When Gorbachev surprisingly accepted Perle’s zero option and Reagan agreed to take yes for an answer, Podhoretz thundered that Reagan betrayed the cause of anticommunism. He was incredulous that Reagan bought the “single greatest lie of our time,” that arms control served the ends of peace and security. In 1986 Reagan traded a Soviet spy for the release of an American journalist; Podhoretz protested that Reagan “shamed himself and the country” because of his “craven eagerness” for an arms agreement with Gorbachev. The culture of appeasement was winning. By playing on the fear of war, Podhoretz claimed, the culture of appeasement turned even Ronald Reagan into a servant of the Big Lie.10

Some neocons resisted this verdict, gamely relieving Reagan of responsibility for the foreign policies of his administration. Under the slogan, “let Reagan be Reagan,” “they blamed a series of Reagan officials—Alexander Haig, James Baker, Michael Deaver, and finally George Shultz—for pushing Reagan toward a policy of “Finlandizing” appeasement. But Podhoretz spurned these pious evasions. The Reagan administration was craven and foolish because that was Reagan’s character, he charged. The real Reagan was not the courageous anticommunist of Reagan speeches but a vain politician whose greed for popularity drove him into the arms of the Soviets. Reaching for the ultimate insult, in 1986 Podhoretz desperately announced that Reagan had become a Carter clone. But although poor Carter never got away with being Carter, he complained, it seemed that Reagan would get away with it.11 The only hope for his administration was for Reaganites to stop ganging up on scapegoats like Shultz and vent their rage at Reagan himself. “Maybe if they did,” he wrote, “the President would think twice before betraying them and his own ideas again.”12

To Podhoretz and the hardest-line neocons, America stood in greater danger than ever before, because it faced a Soviet leader who had figured out how to strengthen the Soviet empire and disarm the West. Gorbachev was a cunning Leninist who seduced America into lowering its guard. He softened up Western opinion by making the world less afraid of the Soviet Union. Neocons relied on the doctrine of totalitarianism to explain what was happening. According to this doctrine, the twin pillars of communism were the absolute domestic power of the Communist Party and the duty to create a communist international order. It was absurd to believe that any Soviet leader would try to democratize the Soviet system or curb its drive for world domination. Just as Lenin loosened economic restraints during the 1920s to impede an economic collapse, Gorbachev opened the Soviet system just enough to entice Western aid and thereby save his totalitarian structure.13

The neocons debated whether Gorbachev had found a cunning way to disarm America, but they agreed about totalitarianism. In the upper regions of the first Bush administration, months after Reagan proclaimed the end of the Cold War? Dick Cheney and Paul Wolfowitz maintained that the Cold War was still raging. Charles Krauthammer doubted that Gorbachev had suckered th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Neocons in Power

- 1. “Trotsky’s Orplians”: A Brief History of Neoconservatism

- 2. “The Bully on the Block”: Paul Wolfowitz, Colin Powell, and American Superpowerdom

- 3. “An Empire, If You Will Keep It”: Charles Krauthammer, Joshua Muravchik, and the Unipolarist Imperative

- 4. “Benevolent Global Hegernony”: William Kristol, Robert Kagan, and the Project for the New American Century

- 5. “The Road to Jerusalem Runs through Baghdad”: The Iraq War, Hardline Zionism, and American Conservatisms

- 6. Conclusion: An Empire in Denial

- Notes

- Index