![]()

1 Introduction

This book has as its theme the development of the Bronze Age in Europe outside the Aegean area. In geographical terms, the territories surveyed range from the Atlantic islands and maritime coastlands to the Carpathians and the Black Sea, and from the great river valleys and plains of the north to the coasts of the Mediterranean. Within this great variety of environments we have attempted to describe some of the important developments in European prehistory from c.2000 to c.700 BC.

We do not see the European Bronze Age as a period that can be easily separated from preceding or succeeding prehistoric developments, and in many ways the divisions Neolithic – Copper Age – Bronze Age – Iron Age become more and more artificial as cultural and environmental evidence for continuity accumulates through landscape as well as typological studies. However, for the purposes of this book, we have had to adopt a chronological framework based upon an arbitrary definition for the Bronze Age. What we have taken as defining features are the regular occurrence of metal-working in many communities, and a general date of c. 2000 BC for certain areas where metallurgy was never, or only later, established as a major industry.

Copper had been used since the earliest Neolithic in those parts of Europe where its appearance on the surface was most obvious, and the later Neolithic groups in east-central Europe are more properly termed Copper Age, so great was the quantity of implements produced. But metal forms in the Copper Age are simple and restricted: awls, ornamental discs of sheet bronze, hammered flat and perforated for attachment to clothing, tanged daggers, spectacle-spiral pendants, spiral beads, and – in greatest profusion – shaft-hole axes and axe-adzes of massive appearance. Hand in hand with this production of copper went that of gold, which was used in quantity for ornaments, especially ring pendants, spiral beads and a few other forms. Copper Age communities in central Europe built fortified villages by lakes or on hilltops, and many settlements were placed near copper ore deposits; there is much evidence for local metallurgy, as well as general similarity throughout the region in total industrial assemblages. The differences between this Copper Age evidence and that of the traditional Bronze Age are often minimal in certain areas, and this is why Müller-Karpe would have us now take a large part of the traditional ‘Early Bronze Age’ as ‘Copper Age’,1 but we feel it is still possible to draw a line between an ‘Incipient Metal Age’ and a ‘Full Metal Age’, regardless of the actual alloys used. It will be objected that such a line will be as arbitrary as any other, including Müller-Karpe’s, and to this we can only reply that in the first place changing the established system will be misleading, and, in the second, a simple and reasonably objective test may help to eliminate these difficulties. In Central Europe the criterion of a Metal Age should be that most of its tools and weapons and at least some of its ornaments, should be of metal; and that there should be evidence of extensive and local extraction and working of metal.2

In Central Europe, hoards of tools (for it is on hoards and not single finds that one should depend) continue, right up to the threshold of the Bronze Age, to be made of stone and bone. In Austria, for example, the Lengyel and related Late Neolithic groups like Wolfsbach and Kanzianberg contain large stone-axe and flint collections, as does the succeeding Baden group.3 Only with the advent of the late Copper Age groups like Ossarn does metal start to appear in any quantity, and not until the time of the Ringbarren hoards can we speak of an absolute predominance in tool and weapon types of metal over stone.4

The vast increase in the quantities of metal found as tools and implements is a natural reflection of increased working of copper veins at the main mining centres of central Europe. It is now forty-five years since Pittioni concluded that the famous mines of the Bischofshofen-Mühlbach area in upper Austria started to be exploited intensively during the period of the Ringbarren hoards, that is, in the Early Bronze Age.5 The finds from the settlement on the Klinglberg near St Johann in Pingau included pottery with slag inclusions and the association of these sherds with a flanged axe clinched the matter. It now seems quite clear that the extensive mining of copper, such as we have discussed elsewhere (p. 63), is, in central Europe, the concomitant, if not actually the cause, of the development of the Early Bronze Age in the area. The date of this transition to the Bronze Age is likely to be in the late third millennium BC, although naturally it will always remain impossible to pinpoint the exact time and place of our artificial transition to the Bronze Age. A further help, however, can come from the recognition of the alloying of copper with tin or arsenic, to produce the metal bronze, and here the analyses of metal objects (noted below) can be of value; using these, we may point to the first objects made of tin-bronze, or the first two-piece moulds, and suggest these as general termini ante quos for the Bronze Age. Such beginnings, however defined, were not of course uniform over the European continent, either in time or amplitude, and previous and recent studies of material of Copper Age and Bronze Age character, utilizing terminologies based upon local finds and sites, have led to the identification of a bewildering variety of differing cultural groups in the early stages of the Bronze Age of central Europe and elsewhere. We have tended to avoid the proliferation of names of archaeological groups in this book wherever possible.

Fig. 1 Opening of the Trindhoj barrow in 1861, under instructions of King Frederik VII of Denmark. The oak coffin exposed had already been emptied before the archaeologists Worsaae and Herbst, anatomist Ibsen and artist Kornerup (whose drawing this is) had arrived on the scene. Further in the mound lay another oak coffin with a clothed body (see fig. 92 for reconstruction).

(From Skalk, 1963, no. 3)

The history of Bronze Age studies is concerned with two main aspects. The first, in the earlier nineteenth century, resulted in the excavation of thousands of burial monuments (fig. 1), and the destruction of evidence of all kinds; there were few areas possessing museum facilities and adequate provision for storage of records, and many of the outstanding monuments were rifled for precious metals. The early conservation of organic materials from a few burials in the north are a welcome exception.6 These matters are referred to in the relevant chapters below.

The second major aspect of Bronze Age studies, initiated in the nineteenth century and continuing up to the present time, is the attention paid to typology, particularly of metal products but also pottery and stone.7 The fine quality of workmanship, the opportunity to express local stylistic preferences in shape and decoration, the deposition of products in hoards or graves with other objects, all have created the chance to describe and discuss the evolution of types, the changing fashions and preferences of Bronze Age communities, the regular association of objects and the possible trading patterns developed for the dissemination of products. These studies, and there are thousands of them, can create opportunities for the further understanding of Bronze Age societies, but not if they are taken in isolation and treated as end products in themselves. In this book we have attempted to reduce the typological content to an acceptable minimum, while emphasizing that such studies are still vital to an overall picture of the Bronze Age. A short survey of the major forms appears elsewhere in this Introduction.

The surviving evidence for the Bronze Age is massive. Apart from the many thousands upon thousands of metal artifacts and pottery vessels, quantities of flint and stone work exist, and the decorated rock surfaces as well as clay and metal objects also form a body of data suitable for study. Cemeteries of inhumed or cremated remains abound, from a few burials to many hundreds. Settlements in a variety of situations are becoming increasingly well-known through discoveries of new sites and further examination of the old. Although stratified settlements are not widely distributed, the tell-type occupations in east-central Europe, and cave sites in the west, allow some measure of stratigraphical detail which is lacking from the open flat settlements so characteristic of many areas in Bronze Age Europe. Lake-side settlements, preserved by peats or muds, create their own unique opportunities. Increasingly, environmental data and organic remains are becoming available for study, through re-examination of old sites and selection of new areas for research. The development of patterns of land-use, the take-up of new land, and the methods of exploitation for food-production, all of these are under examination in many areas of Europe, and this is one of the most encouraging aspects of Bronze Age studies.

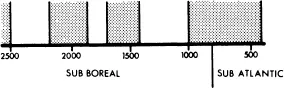

Closely related to these landscape studies are questions of alterations in natural conditions through land-take (landnam) and land-exhaustion, through forest clearances, alterations in water levels, and through climatic changes. Some of these matters are referred to elsewhere in this book. In terms of climate, the Bronze Age falls within Pollen Zone VIII (in the Blytt-Sernander system), that is, the Sub-boreal period which lasted about 2,500 years, c. 3000–500 BC. A variety of approaches have shown that the climate of the Sub-boreal was warm and rather dry, with considerable variation in humidity, in contrast to the warm but wet conditions of the preceding Atlantic period and the cooler, wetter conditions of the succeeding Sub-atlantic.8 During the Sub-boreal, brown soils predominate, and the process of podsolization was temporarily halted; the growth of peat bogs similarly slowed down, and periodic desiccation occurred in them. Lake levels fell considerably but still fluctuated wildly; sea levels were generally higher than before but close to present-day values.

Fig. 2 Climatic oscillations during the later Sub-boreal and early Sub-atlantic phases in Europe. Stipple represents relatively cool and/or moist episodes; un...