![]()

1 Immigration and integration in Singapore

Trends, rationale and policy response

Yap Mui Teng

Introduction

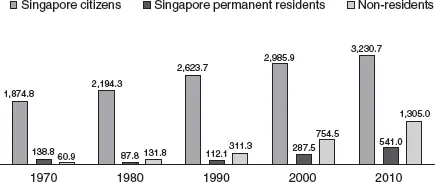

According to the latest round of the Singapore Census of Population carried out in 2010, ‘non-residents’ or foreigners on various types of work, student, dependant and other temporary passes made up about 26 per cent, or 1.3 million, of the total population of nearly 5.1 million persons that year. This was significantly higher than the number found in Singapore’s first post-independence census in 1970 when there were only 60,900 non-residents, forming 3 per cent of the total population (Figure 1.1). The number and proportion of foreigners further increased to 1.49 million or 28 per cent of the total population of 5.31 million in 2012, the majority (80 per cent) of whom were work pass holders and the rest students and dependants of Singaporeans and work pass holders (National Population and Talent Division, 2012b, p. 5).

The figures on the non-resident population do not include the growing numbers of foreigners who have taken up Singapore permanent residency and citizenship, and are considered part of the resident population. For example, the number of new permanent residency (PRs) granted rose from about 23,000 in 2000 to over 79,000 in 2008 and nearly 60,000 in 2009, before falling just below 30,000 in 2010–2011; the number of new citizenships granted rose from about 6,000 to about 20,000 over the period 2000–2009 before declining to about 16,000 in 2011 (Wong, 2007, 2010; National Population Talent Division, 2012b, Chart 11).The share of PRs in the total population rose from 7 to 11 per cent over the 2000–2010 decade, while the share of citizens fell from 74 to 64 per cent over the same period. With the latest wave of high in-migration in the decade of the 2000s, an estimated 43 per cent of the total population in 2010 were foreign-born (Table 1.1). It would appear that Singapore is a land of immigration again.

Figure 1.1 Population by residency status (000s) (source: Singapore Department of Statistics, various census years 1970–2010).

The increase in foreigners has taken place after a period of indigenisation lasting until about 1980 when the vast majority of the population (approximately four out of five) were born locally. With this influx of foreigners, the issue of foreign–local integration has also come to the fore as Singaporeans experienced and expressed disquiet over a range of economic and social concerns at levels they had not done before. In this connection, the government has also adopted a more proactive stance on integration than has hitherto been the case. The task of integration is perhaps more urgent now as the source countries from which immigrants are drawn are also more diverse than before.1

The remaining sections in this chapter begin with a review of Singapore’s immigration policy, its rationale and outcomes. This is followed by an examination of its policies and programmes on the integration of foreigners and a discussion on the Singapore integration model. The focus is on recent developments, even though Singapore has had a long history of receiving immigrants.

Singapore’s immigration policy, rationale and outcome

Singapore adopts a two-pronged policy towards foreigners who want to live, work or study in the country. As former Deputy Prime Minister and Minister-in-charge of population matters Wong Kan Seng has noted, the vast majority of foreigners in Singapore are transients who will leave the country after the expiration of their work or other short-term passes (Wong, 2010; Cai and Ong, 2011). Low-skilled and semi-skilled foreigners are allowed into the country on work permits, which are valid for two or three years in the first instance (Employment of Foreign Manpower Act, Employment of Foreign Manpower (Work Passes) Regulations 2012, c.91A Fourth Schedule), and even though the permits are renewable, holders are expected to return to their home countries upon the completion of their contracts or when they are no longer employed in Singapore. Generally those who do the dirty, dangerous and demanding (‘3D’) jobs that Singaporeans do not want and which employers have difficulty recruiting local workers for (including domestic workers or housemaids, construction workers and workers in the marine and processing sectors), work permit holders may not marry Singaporeans without the prior approval of the Controller of Work Passes, have children or settle in the country (unless their marriages have been approved or they have acquired skills and qualifications that qualify them for higher-level work passes (ibid., Fourth Schedule).

Table 1.1 Proportion of foreign-born, 1921–2010

| Year of census | Total population (000s) | Foreign-born (%) |

| 1921 | 425.9 | 70.9 |

| 1931 | 567.5 | 63.1 |

| 1947 | 938.2 | 43.9 |

| 1957 | 1,445.9 | 35.7 |

| 1970 | 2,074.5 | 25.6 |

| 1980 | 2,413.9 | 21.8 |

| 1990 | 3,047.1 | 24.0*/23.3** |

| 2000 | 4,027.9 | 33.4*/33.0** |

| 2010 | 5,076.7 | 42.6*/42.2** |

Source: Author’s calculations.

Notes

* Estimate assuming all non-residents are foreign-born.

** Estimate assuming non-resident births in previous decade are local-born and subtracted from non-resident population.

On the other hand, foreign professionals, skilled workers and investors, or ‘foreign talent’, are not encumbered with such restrictions and they are indeed encouraged to settle in Singapore and even take up citizenship after a period as employment pass holders and PRs (ibid., Sixth Schedule). Such foreigners are desired as settlers as they are deemed to augment the skills and quality of the working population. They may also bring their spouses, unmarried minor (below 21 years old) children and certain extended family members (such as their parents) on dependants’ or long-term visit passes, a privilege not extended to their less-skilled or less-qualified counterparts (Ministry of Manpower website).

Another group of foreigners that the government wishes to attract, foreign students, are also encouraged (sometimes with attractive scholarships) to study in Singapore with the hope that at least some of these will remain and contribute economically to the country and augment the domestic talent pool. The retention rate among these students is not known as there have been no reports on the numbers that have taken up residency upon the completion of their education.

Marriage to a Singapore citizen does not automatically confer on the foreign spouse the right to permanently remain or legally reside in Singapore. Apart from those who qualify for residency on their own merit, foreign spouses may be granted long-term visit passes (LTVP) in the first instance. Approval for residency will depend on the stability of the marriage (as assessed by criteria such as the duration of the marriage), whether the couple has children and the ability of the Singaporean partner to provide for the family. Liberal granting of long-term visit passes is a departure from the past when foreign spouses were expected to remain in their home countries and given only short-term social visit passes until their application was approved. Since April 2012, an enhanced scheme, the Long-Term Visit Pass plus (LTVP+) allows foreign spouses a longer period of stay, enables them to work on the strength of a letter of consent (similar to dependants of employment pass holders) and enjoy subsidised healthcare benefits (Immigration and Checkpoints Authority, 2012). The change is in response to an increase in Singaporeans marrying foreigners.

In the event, as mentioned in the preceding section, the number of foreigners and foreign-born citizens and PRs residing in the country now forms a significant proportion of the population. The growth has been especially rapid in the second half of the last decade when the government liberalised the conditions for the recruitment of foreigners to allow businesses to take advantage of the extraordinary opportunities for economic growth (Wong, 2010). In an ironic twist, more foreigners chose to remain in Singapore and applied for permanent residency and citizenship as the 2008–2009 recession hit (Chew, 2009). The Singapore government took advantage of this surge in applications (Wong, 2010).

Drivers of Singapore’s immigration policy

Ensuring sufficient manpower for economic growth and mitigating the impact of ageing are two other needs that must be managed in achieving a sustainable population profile for Singapore.

(Wong, 2011)

Economics has always been the main driver of Singapore’s foreign manpower policy. After closing the country to immigration (except for family reunions) at the time of independence in 1965, the government began to open its doors to meet the labour shortage generated by industrialisation and rapid economic growth. This is still the case currently. Amidst greater economic volatility in the early 2000s, the government’s strategy has been to maximise growth in good economic times. This growth has been fuelled mainly by increasing the work-force through importing more foreign manpower, because the domestic population growth in Singapore has slowed due to the prolonged low, well below the replacement level, total fertility rate (TFR). Although probably unfa...