![]()

Part I

![]()

lisahunter, Wayne Smith and elke emerald

Keywords: Theoretical tools, Habitus, Field, Capital, Practice, Hexis, Doxa, Symbolic violence, Reflexivity

Here we introduce Pierre Bourdieu and those of his theoretical tools that have offered particular insight into studies of physical culture. We briefly explain who Pierre Bourdieu was and explain his tools, including Habitus, Field, Capital, Practice, Hexis, Doxa, Symbolic violence and Reflexivity.

Pierre Bourdieu was a French social theorist who provided us with a reflexive social theory that drew from sociology, philosophy and anthropology. He was born in France to traditional rural peasant farmers in a small country town, Denguin, in 1930 (see Grenfell 2008 for more details). Knowing a little about his life situates where his ideas came from and what he was trying to do through his conceptual tools as developed within, and applied to, French society at a particular time and from his position within that society. As his work argues, he is a product of society, all the while acting with some form of agency to shape that society. He drew on the work of Émile Durkheim, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Martin Heidegger, Edmund Husserl, Marcel Mauss, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Karl Marx, Max Weber, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Blaise Pascal among others. Bourdieu was a social activist, known in France through the media and, over time, beyond France, with translations of his work into many languages. His work was taken up quickly, but behind his contemporaries such as Foucault, in the USA. Working in France, he was a prolific writer up until his death in 2002.

Figure 1.1 Pierre Bourdieu 1930–2002

As a means of understanding practice, Bourdieu provided conceptual tools that articulate the dialogue between structures that shape a society and their interaction with the individual person. Significantly, Bourdieu located the body as an important locus of social theory. His conceptual tools offer a theory of embodiment that is useful for understanding deeply entrenched forms of embodied existence and differentiated social power relations. Using these tools we can come to some understanding of how we embody culture while at the same time, through our practices, changing and/or replicating the status quo. The ontological and epistemological positioning of corporeality is of particular importance in the context of this book: the/our body’s definition and neglect within our practices and research concerning physical culture.

Bourdieu also developed historical, political and sociocultural critiques of education systems in an attempt to explain how, despite a popular assumption of equity, schooling and higher education reproduce structures (such as social class) and dominant inequitable ways of knowing, acting and being (Bourdieu and Passeron 1977). His theories went beyond the formal institutions of schooling and universities to consider broader potentially educative or socialising institutions such as television (Bourdieu 1998b), art (Bourdieu and Johnson 1993) and sport (Bourdieu 1988a). Through Bourdieu, we can recognise that movement and the body are constituted in physical cultures both in formal institutional experiences (school and university) and in non-school/university experiences in sport, leisure, dance and so on. These physical cultures, their structures and social orders of legitimation and domination become naturalised as ‘common sense’ or ‘taken-for-granteds’ by means of systems of classification instituted through our bodily social practices. Chapters 2–15 explore many different fields and sub-fields of physical culture: dance, teacher education, surfing, school physical education, rugby coaching, boxing, sport and snowboarding.

Below we provide an explanation of some of Bourdieu’s tools. Our explanations are designed as an introduction for you to then explore the chapters that employ these tools. The concepts are by no means simple or uncontestable, so our explanations are not without this caution. Further, we advise that you read other sources that have endeavoured to ‘define’ Bourdieu’s concepts, and indeed, read Bourdieu’s own explanations. Bourdieu’s own explanations are complex, multilayered, revisited and developed over his lifetime, and situated in his context. While this might seem daunting, as his work is arguably difficult to fathom at first, it is in the practice of grappling with and playing with his concepts that scholars have been rewarded with new ways of understanding the contexts and practices within which they work.

It would be remiss of any of us not to appreciate that these concepts are situated in a particular time and place, and further, that English was not Bourdieu’s writing language, so that his works in English are translations. You will note, as you read more widely, that like many sociological tools, Bourdieu’s have been used well, but they have also been used poorly, inappropriately, for means other than those originally designed, and in new or misleading ways that Bourdieu himself probably never imagined possible. Even in putting this chapter together we had many discussions to clarify what we think Bourdieu’s concepts mean and how to communicate this meaning to you within the constraints of this book. Meaning is a slippery thing, but Bourdieu’s ideas were translated and clarified through and with others such as Richard Nice (Bourdieu and Nice 2008) and Lois Wacquant (1989) to try and make the concepts comprehendable. And thus do ideas weave their magic, inspiring new practices, challenging the status quo, and perhaps even reifying the status quo! Nonetheless, it is in the application in our practices of concepts such as those Bourdieu offered that we can form a language to constitute one way of ‘knowing’, albeit partially and situatedly, what might be going on in the physical cultures within which we operate. It also acts as a looking glass to our already held ideas and beliefs about our worlds and our ways of knowing our worlds. That is the challenge for the authors in this book. Not all will agree on how they use Bourdieu’s tools, nor the exact meaning of those tools, but it is in their use that we remain open to their potential to help us understand ourselves and our world. It is also important to note that not all authors in this book necessarily agree with Bourdieu’s concepts for one reason or another, some of which will be explicated in the book. But it is in getting to know a theorist and her/his ideas in depth and in context and then applying them to our world that we clarify our own ontologies, epistemologies, methodologies and theories. For you, this book may be just a beginning of this process. For us, this book is just one of many cycles as we continue to clarify, change and play with ongoing dialogues that include theories and practice.

Bourdieu: the tools

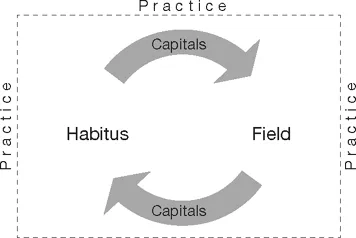

Figure 1.2 The interaction between field, habitus and capital through practice

Practice

Practice is one of Bourdieu’s most widely used concepts and one that was the focus of much of his own empirical work. In this first section we explain the notion of practice and show how it is often used in conjunction with Bourdieu’s other conceptual tools.

Bourdieu proposed (1980/1990) that it is our taken-for-granted, recursive daily practices that reveal the visible, objective social phenomena that determine the nature of our society. His own field-based anthropological research led him to conclude that practice should be the primary focus of all social analysis, because it is practice, derived from the subconscious, that reveals both the logic of the actions of individuals and the structuring of the social space in which they are embedded. In his The Logic of Practice (1980/1990), Bourdieu argued that objects of knowledge are constructed in our taken-for-granted practice and that ‘the principle of this construction is the system of structured, structuring dispositions, the habitus, which is constituted in practice and is always oriented towards practical functions’ (p. 52). We will explain more about habitus and its structured and structuring function in the next section, but for the moment we will continue to focus on the importance of our everyday, taken-for granted practices.

Social practice, what we do as individuals and social groups, is the product of processes that are neither wholly conscious nor wholly unconscious (Bourdieu 1980/1990). Rather, social practice is the product of a subconsciously embodied and embedded, taken-for-granted, practical logic. Bourdieu qualified this by stating that although practice is accomplished without conscious deliberation, it is not without purpose. Individuals, actors, or agents, do have goals and interests, but these are, in part, located in their own experience of reality – their practical sense or logic – rather than their conscious, rational deliberations. In this way, practical sense orients our choices, though not deliberately (1980/1990). Social practice, in all its complexity, is not determined by inflexibly-structured rules, recipes, or normative models, but rather by a sub-conscious practical logic (practical sense or practical consciousness) with an inherent fluidity and indeterminacy. This practical logic is, in part, determined by the actor’s embodied understanding of how things ‘are’ or ‘ought to be done’: that is, the nature of their reality.

Bourdieu often used an analogy of how players engage in sport or games to explain the nature of practical logic. He suggested that it is our practical logic that enables us to intuitively ‘read the game’ and act accordingly. He argued that although games have set parameters and rules (structures), it is a shared, intuitive, practical sense of how the game is played that enables the players to play the game and implement strategies in particular ways. It is the players who determine the nature of the game, not necessarily in a conscious way, and if necessary change the rules when they no longer serve the needs of that/their game. With reference to Bourdieu, Harker et al. (1990: 7), expressed this analogy as follows:

[Bourdieu’s] analogy with games is an attempt to provide an intuitive understanding of the overall properties of fields [of practice]. First, a sphere of play is an ordered universe in which not everything can happen. Entering the game implies a conscious or unconscious acceptance of the explicit and/ or implicit rules of the game on the part of the players. These players must also possess a ‘feel’ for the game, which implies a practical mastery of the logic of the game.

In a cyclical or dialectica...