![]()

The Origins of Intergroup Contact Theory

One of the worst race riots in the history of the United States occurred in Detroit in 1943. But while Black and White mobs raged in the streets, Whites and Blacks who knew each other not only refrained from violence but often helped one another. Automotive workers and university students continued to work and study side-by-side. Families hid neighbors of the other race from threatening rioters, and those Blacks and Whites who were close friends were especially protective of each other (Lee & Humphrey, 1968).

Such interpersonal humanity in the face of intergroup strife is not uncommon. During the 1990s, for instance, the world watched in horror as “ethnic cleansing” unfolded in Bosnia-Herzegovina (Oberschall, 2001). The terror of genocide was widely reported from this region of the former Yugoslavia. But largely unnoticed were the many households of all ethnic groups who hid friends of rival ethnicities whose lives were threatened.

Similarly, a mixed Arab and Jewish street in Jaffa, Israel, witnessed repeated neighborhood tragedies in October 2000. Each group rioted against the other, followed by a sudden flood. A Jewish mother and her children were trapped in their apartment by the rising water. And an Arab family, neighbors in the same apartment building, braved the flood, broke down bars on the window, and rescued the mother and two of her children (Copans, 2000).

Consider also research by Oliner (2004) and Oliner and Oliner (1988) on the rescuers of Jews in the midst of the Holocaust. These tireless investigators interviewed more than 600 European Christians, and focused on more than 400 rescuers who had saved Jews during the war. Bystanders, who neither saved Jews nor participated in the resistance, served as the key comparison group. How do these two groups differ?

The rescuers do not fit the widespread Western image of the “hero” – the lone outsider facing off evildoers as in the classic motion picture, High Noon. More than bystanders, rescuers lived on farms or in small villages. Here there was a strong sense of community and hiding the hunted was easier. They benefited from more supportive networks, including family members; and the desperate more often asked them for help. After the war, the rescuers achieved higher status occupations and were more active in their communities than bystanders.

Intergroup contact played a crucial role in this behavior that extends far beyond mere reduced prejudice. Just as contact theory would predict, the rescuers had significantly more contacts than bystanders with Jews in a variety of roles prior to the war (Oliner & Oliner, 1988, p. 275). Thus, they more frequently had had Jews as friends (p<.0001), neighbors (p<.006), and coworkers (p<.03). In addition, the rescuers also had a significantly wider variety of friends beyond that of their greater contact with Jews. When asked, “While growing up, did you have any close friends different from you in social class,” 62% of the rescuers, but only 36% of the bystanders, answered “yes” 1 (Oliner & Oliner, 1988, p. 304).

Such dramatic examples offer hope that intergroup contact can be a significant remedy for combating prejudice and hostility between groups. Many commentators have held optimistic views regarding the potential for intergroup contact to improve intergroup relations. A popular refrain among advocates of integration is “if only we could get people from different groups to come together,” then we would be able to achieve improved relations between groups. Unfortunately, achieving positive effects of intergroup contact is not always so simple.

Think about it. African Americans and European Americans have had more contact in the southern United States than in other parts of the nation. Nonetheless, the South has witnessed the most severe racial oppression. In South Africa, people of Black African and White European descent have lived in close proximity more than in any other part of Africa, yet the country has endured intense racial conflict. From these examples, it almost appears as if the more contact between peoples, the more – not less – prejudice and conflict will result. Some observers have come to that conclusion (e.g., Baker, 1934), but this view would be just as fallacious as the assumption that contact by itself offers a panacea for prejudice and intergroup conflict (Hewstone, 2003).

In this volume, we will demonstrate that intergroup contact actually does typically decrease intergroup prejudice and hostility – but not always or under all conditions. While many of the social sciences share an interest in intergroup contact (e.g., Blake, 2003; Crain & Weisman, 1972; Mutz, 2002), it is social psychology that has intensely focused on studying its complex effects. And it is this work that we will be describing in particular detail.

The Historical Development of Intergroup Contact Theory Early Thinking and Practice

So, what happens when groups interact? Theorists and practitioners began to speculate about the effects of intergroup contact long before there was a research base to guide them. 19th Century thinking, dominated by Social Darwinism, was quite pessimistic. In particular, William Graham Sumner (1906), a Yale University sociologist and an Episcopal minister, held that intergroup contact almost inevitably led to conflict. He believed that hostility toward outgroups simply follows as a consequence of an ingroup’s sense of superiority. Because Sumner also believed that most groups felt themselves to be superior to other groups, his theory viewed intergroup hostility and conflict to be natural and inevitable outcomes of contact. Some more recent perspectives make similar predictions (see Jackson, 1993; Levine & Campbell, 1972).

20th Century writers continued to speculate about intergroup contact without empirical evidence. Some persisted in believing that contact between races, even under conditions of equality, would only breed “suspicion, fear, resentment, disturbance, and at times open conflict” (Baker, 1934, p. 120). Many of these writers, like Sumner himself, were not-so-subtly defending the South’s then-existing pattern of rigid racial segregation in schools, neighborhoods, and public facilities. But writers following World War II were more optimistic in their views. Hence, Lett (1945, p. 35) held that shared interracial experiences with a common objective led to “mutual understanding and regard.” Instead, when groups “are isolated from one another,” wrote Brameld (1946, p. 245), “prejudice and conflict grow like a disease.”

The first major effort to achieve widespread intergroup contact followed World War II – after Adolf Hitler had given prejudice an exceedingly bad name. A popular crusade formed to condemn both racial and religious prejudice in the United States. Called the Human Relations Movement, it sought to end prejudice and correct negative stereotypes. Yet this attempt was as naïve as it was well-intentioned. The Movement placed its complete faith in educating racial groups about each other and having different groups interact. It avoided controversy by not directly seeking the institutional changes necessary to enhance intergroup contact and combat discrimination in jobs, housing, and education. Rather, it invested its energies in celebrating Brotherhood Week each February and hosting Brotherhood Dinners for all groups to come and meet each other once a year.

The Movement’s guiding premise was that prejudice derived largely from ignorance. If only we could interact and come to know each other across group lines, went the reasoning, we would discover the common humanity we share. The Movement, noted Drake and Cayton (1962, p. 281), projected an “[a]lmost mystical faith in ‘getting to know one another’ as a solvent of racial tensions….”

To be sure, ignorance is a factor in intergroup relations (Stephan & Stephan, 1984). But this factor alone does not account for the many situational and institutional barriers that perpetuate prejudice between groups. Moreover, the Movement did not understand the complexity and variability of intergroup contact effects – issues that are the focus of this book.

Early Research on Intergroup Contact

Nonetheless, these initial efforts by the Human Relations Movement sparked early investigations of intergroup contact by social psychologists and sociologists. Research interest in the topic grew logically from these fields’ emphases on intergroup relations, social interactions, and the power of situations to shape behavior. University of Alabama researchers were among the first to conduct a study that indirectly examined the effects of contact (Sims & Patrick, 1936). Their initial results were not encouraging, although it should be emphasized that their study did not measure intergroup contact directly. With each year that students from the North attended the tightly segregated southern university, their anti-Black attitudes increased. Because the university’s faculty and student body were then exclusively White, Northern students were likely to have had little contact with Black peers and authorities, and more likely to have met only Blacks in lower status positions. They were also influenced by Alabama’s extremely racist norms of that period.

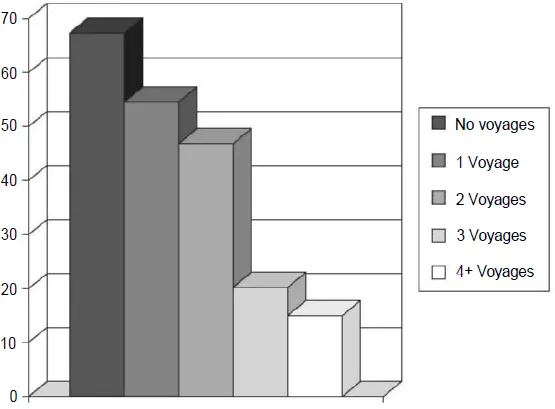

Later studies investigated Black–White contact more directly and under more favorable conditions. After the desegregation of the Merchant Marine in 1948, close bonds developed between Black and White seamen on the ships and in the maritime union (Brophy, 1945). Consequently, the more voyages the White seamen took with Blacks, the more positive their racial attitudes became. But their racial prejudice did not evaporate with a single interracial voyage. What we see in Figure 1.1 is an almost linear effect – one by one, the more interracial voyages the White seamen took, the less anti-Black prejudice they expressed.

Similarly, Kephart (1957) found that White police officers in Philadelphia who had worked with Black colleagues differed sharply in their racial views from other White police officers. They offered fewer objections to teaming with a Black partner, having Blacks join their previously all-White police districts, and taking orders from qualified Black officers.

FIGURE 1.1 Prejudice percentages by interracial voyages. Adapted from Brophy (1945, table 9, p. 462).

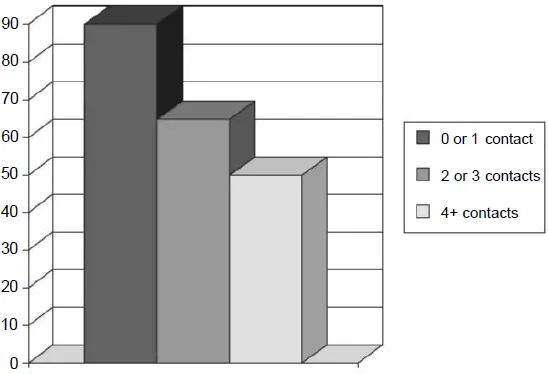

Gordon Allport contributed to this early research (Allport & Kramer, 1946). Together with his then-graduate student, Bernard Kramer, he tested the effects of equal-status contact on the anti-Jewish attitudes of non-Jewish undergraduates at both Dartmouth College and Harvard University. As illustrated in Figure 1.2, an almost linear negative effect again emerges – the more equal-status contacts the non-Jewish students reported having had with Jews, the less they reported anti-Jewish prejudice.

As these early studies grew in number, the Social Science Research Council asked the Cornell University sociologist, Robin Williams, Jr., to review the research on intergroup relations. Williams’ (1947) monograph, The Reduction of Intergroup Tensions, offers 102 testable “propositions” on intergroup relations that included the initial formulation of intergroup contact theory. He stressed that many variables would influence contact’s effects on prejudice – such as the relative status of the participants, the social milieu, the level of prior prejudice, the duration of the contact, and the amount of competition between the groups in the situation. In particular, he stressed that contact’s positive effects are maximized when: (1) the two groups share similar status, interests, and tasks; (2) the situation fosters personal, intimate intergroup contact; (3) the participants do not fit the stereotyped conceptions of their groups; and (4) the activities cut across group lines. This initial statement is apparently the first formal presentation of what has become intergroup contact theory. Though rudimentary, Williams shrewdly foresaw many of the findings of intergroup contact research that we will be discussing throughout this volume.

FIGURE 1.2 Prejudice percentages by equal-status contacts. Adapted from Allport and Kramer (1946, table 8, p. 23).

But there were potential problems involving self-selection and causal direction in these early studies. For example, it could have been that the more tolerant White seamen at the outset signed on for ships with Black seamen, that more tolerant White police initially chose to work with Black colleagues, and that White students who had had equal-status contact with Jews were already more tolerant before the intergroup contact. This problem of causal direction must always be kept in mind when judging intergroup contact effects. Did the contact cause the reduced prejudice, did the more tolerant seek the contact, or was it bidirectional? Longitudinal research reveals that both causal paths operate with roughly equal strength (Binder et al., 2009; Sidanius, Levin, Van Laar, & Sears, 2008), although some work suggests that the contact-to-prejudice path may be stronger (see Dhont, Van Hiel, & Roets, under review-b; Pettigrew, 1997a). This critical issue of causal direction will be discussed throughout the book.

In 1949, Samuel Stouffer and his colleagues’ extensive study of The American Soldier provided the first massive field test of intergroup contact’s effects. Using an ingenious quasi-experimental design, Stouffer showed that the experience of fighting side-by-side with African-American soldiers in the desperate Battle of the Bulge in eastern Belgium during the frozen winter of 1944–1945 sharply changed the attitudes of White American soldiers. These altered attitudes were found among Southerners as well as Northerners, and among officers as well as enlisted men. Unfortunately, however, these new attitudes were limited to the fighting situation and did not generalize to non-combat situations. We shall return to this important issue of generalization in Chapter 3.

Inspired by Williams’ writings and Stouffer’s results, research then began to test the theory more rigorously. Field studies of public housing provided the strongest evidence. This work marked the introduction of large-scale field research into North American social psychology. In the most notable example of this work, Deutsch and Collins (1951) interviewed White housewives across different public housing projects with a quasi-experimental design. Two housing projects in Newark assigned Black and White residents to apartments in separate buildings. Two comparable housing projects in New York City desegregated residents by making apartment assignments irrespective of race or personal preference. White women in the desegregated projects reported far more positive contact with their Black neighbors, and, in turn, they expressed higher esteem for their Black neighbors and greater support for interracial housing.

Further p...