eBook - ePub

Innovative Fiscal Policy and Economic Development in Transition Economies

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Innovative Fiscal Policy and Economic Development in Transition Economies

About this book

This book explores the problems of fiscal policy as an instrument of economic and social development in the modern environment, primarily focusing on the transition economies of Eastern Europe, Caucasus, and Central Asia. Evaluating the transformational experience in these countries, this work meets a need for a critical analysis in the aftermath of the 1990s market liberalization reforms, of current trends and to outline the roadmap for future development.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Economics of Transition in the New Century

Lessons Learned and a Future Outlook

1.1 Introduction

As the theoretical debates go on temporary recess, there comes a time for sobering situation analysis. Almost two decades ago, a transformational process ensued in the socialist countries of Eastern and Central Europe and the former Soviet Union (FSU). Despite the length of time that has passed, the outcomes of these social, economic, political, and generational transformations are still high on today’s agenda.

This project is focused on analysis of social and economic processes, and the role of fiscal policy in the countries of the FSU. Excluding the three Baltic states, those are Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. All twelve are members of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) created immediately following the breakup of the USSR in 1991.1 Collectively, economic literature identifies these, and several other Eastern European formerly socialist countries, as transition economies.

A discussion of the CIS transition economies is necessarily predicated by a clarification of the term transition. Broadly, transition is defined as a move from a centrally planned economy to a market-oriented one (e.g. Havrylyshyn and Wolf, 1999). The reference is to the market liberalization process that began in the former socialist countries in the late 1980s–early 1990s.

It is reasonable to assume that the achievement of high living standards, increased productive capacities, sustainable economic growth, diminished income inequality as well as a strict rule of law and democratic polity is the final destination of the process. It then becomes clear that, in the context of the FSU countries, the discussion revolves around a transformational change (as in, e.g., Nell, 1992; and Nell et al., 2007). In fact, economically necessitated changes inspire chain reactions across every fiber of the society. For example, technology changes transpiring in an economy lead to the consequent social and institutional development. Hence transformation is captured as new social forms replace one another, encompassing and building upon the core elements of the prior, adding its own innovative breakthrough. The process is dialectical in nature. It is inherently dynamic and volatile, and requires comprehensive analysis.

One does not require any specific macroeconomic data to realize the complexity of the societal change involved. In the context of transition economies, the transformation that ensued in the early 1990s has been highly controversial to date, taking a heavy toll on social welfare and national economies’ well-being. Despite disastrous setbacks, discussed in this chapter, recent years have shown improvement in welfare across the locale. Surprisingly it has been the increased role of state in each country that has helped improve the situation. The challenge for transition economies of the CIS is now to take up proactive and innovative steps to ensure the sustainability of their improved economic performance of recent years, while managing a diverse set of social issues.

This chapter serves a dual purpose, as an introductory narrative and that of a problem-setting critical analysis. Section 1.2 gets to the heart of the subject matter and briefly outlines crucial aspects of political economy in the former Soviet Union prior to the liberalization reforms of the late 1980s–early 1990s. Then Section 1.3 analyses economic and social reforms of the 1990s with the benefit of hindsight. Section 1.4 also provides a detailed assessment of the region’s performance in more recent years. Structural economic issues are abound and require attention. The final section carries the weight of the analytical argument developed throughout this study. The chapter ends with a Conclusion and Appendix.

1.2 Before the Shock: Notes on the Political Economy From 1960 to 1990

Looking back two decades, one could pinpoint two distinct and interrelated events that gave the symbolic start to the unprecedented political, social, and economic transformation in Eastern Europe and the former USSR. The first was the launch of the perestroika [rus. restructuring] movement in 1985 in the former USSR by the then head of state Mikhail Gorbachev. The other was the breakup of the Berlin Wall in Germany in late 1989. One can see a dialectical bond of both significant events: Gorbachev’s abstract ideas of perestroika and glasnost found their realization in the concrete dismantling of the Berlin Wall, which caused the collapse of the centrally planned and controlled economic, social, and political systems across the entire former socialist locale.

Perhaps it would be surprising to learn that initial efforts bringing such a chain reaction had been in fact aimed at the upgrade of the old order and its preservation, rather than its destruction. Envisioned on the scale of the entire country— the USSR—the first efforts and research were aimed at industrial reorganization and increasing competitiveness of the national economy, with each republic providing an integral link in the overall system. This view is confirmed by a close reading of Shatalin et al. (1990), also known as the 500 Days Program—a blueprint for transition to market economy that we discuss below. Therefore, it is instructive to understand the core issues of political economy that shaped the early transition in the countries of the former Soviet Union.

The history of the region is marked with dramatic events in the twentieth century. The collapse of the Russian Empire comprised of Russia—as the leading state—and smaller provinces that later joined the USSR as republics under the pressure of World War I, and the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 brought the first social and political transformation. The new entity, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, was established. Following disastrous agrarian and industrial reforms of the late 1920s to the 1930s (collectivization and industrialization), the USSR came out as a winning power in the no less disastrous World War II. Both events took an enormous toll on the lives of ordinary people: a death toll that was measured in millions. Yet the country continued its advance to superpower status, being the first to man a spaceship in 1961.

In fact, across the USSR and primarily in Russia and Ukraine, the 1960s and early 1970s saw a rise in urbanization, one of the primary indicators of advancing development (see Nell et al., 2007 on urbanization). By 1980, almost 62 per cent of the entire country’s population lived in the cities. Meanwhile, with a compulsory education system in place, the number of students in USSR universities soared 74 per cent between 1970 and 1980. Research institutes proliferated across the country and science was heavily subsidized by the government (e.g. Kal’yanov and Sidorov, 2004). Healthcare, education, child support, and other non-waged services were state sponsored and nominally accessible to everyone. In many cases, large industrial factories (by definition state-owned) provided their employees with access to subsidized leisure facilities, hospitals, kindergartens, etc.

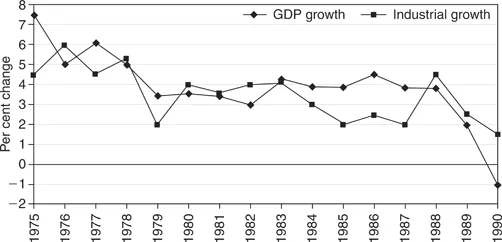

Industrial capacity growth was around 5.5 per cent on average, with slightly exceeding GDP growth at 5.8 per cent (as shown in Figure 1.1). Officials claimed full control over inflation as the government succeeded in instituting a strict price control, particularly on food and basic household items. There was virtually no incidence of involuntary unemployment, and salaries were guaranteed by the state. Overall, despite some hidden hurdles along the way (e.g. difficulties with changing jobs; free movement within and across republics; sealed borders), the countries of the USSR looked optimistically into the future.

Figure 1.1 USSR GDP and industrial capacity growth, per cent change (1975–1990).

However, the first signs of a serious crisis appeared early in the 1980s. By then, the country’s entire economy, knitted with large industrial factories often producing output that the state had to buy back due to inexistent demand, was running on subsidies sponsored by income from raw material exports, mainly energy resources such as oil, coal, and gas.2 Spread across a vast area were factories that produced parts for an intermediate product thousands of miles away, while the final product would be produced in yet another republic.

Consumption goods rationing and cuts in household durables production brought consumer deficits in the early 1980s. In other words, it was difficult to obtain the basic necessities in stores. The situation deteriorated more quickly with distance from major industrial and administrative centers.

Factories’ capital funds had not been upgraded for decades and the living standards of millions of people, especially in rural areas and in republics less advanced in industrial and technological terms (such as countries in Central Asia), plunged. While on paper high macroeconomic indicators seemed unchanged, the real economy came to a stalemate with the growth rate of 2 (and less) per cent.

To sustain even such low levels of economic performance and avoid igniting any social unrest, as Gaidar (2007) notes, the Soviet state relied on high prices for oil and gas in the international markets. Energy resource exports were the source of hard currency, given the Soviet ruble’s inconvertibility, and hence provided the means for the Soviet government to purchase necessary machinery and consumer goods from abroad—primarily from the socialist states of Eastern and Central Europe.

The situation created a paradox when, in the late 1980s, one of the richest and largest countries in the world in terms of natural resources and agricultural lands imported grain from its ideological opposites in the capitalist West. The Soviet Union pressed forward with oil extraction, reaching 12,000 barrels per day in the mid 1980s (US Department of Energy, 2005). However, the luck (and with it sufficient inflows of hard currency) ran out by 1985 when oil prices dropped from approximately US$30 to US$10 per barrel.3

It was against the background of this environment that the Soviet government announced its course for economic restructuring and upgrade—the perestroika movement. Reminiscent of the New Economic Policy and designed and launched in the USSR by Lenin in the 1920s, the reforms of the mid 1980s encouraged the creation of small private cooperatives and promoted entrepreneurship. Practically all factories, with the exception of a few strategic ones in the nuclear and military industries, were encouraged to seek their own sources for operating capital, yet still fulfill state orders, with an option of selling any extra output in the market. In summary, it was the push for economic decentralization from above.

Unfortunately, the announced perestroika reforms did not bear the expected results. Granted greater autonomy from the state, the enterprises were being taken off the state books and were to look for larger funding independently. That was supposed to come from sales beyond the state order target. But in the conditions of fixed prices and a rudimentary financial system, this led to supply diversion as managers worked things out privately, contributing to the barter exchange system on the scale of the entire economy.

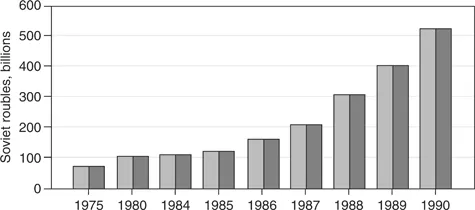

The nominally state enterprises were not designed to produce competitive output to offer in the international markets. At the same time, there was oversupply of redundant produce in the domestic economy. Facing declining global prices for oil, the Soviet government borrowed internally via debt and printed money, virtually bringing the country to “the edge of bankruptcy” (Shatalin et al., 1990: 23). In fact, internal debt between 1985 and 1990 grew 333 per cent (from approximately 120 billion to 520 billion Soviet rubles, as depicted in Figure 1.2). USSR’s foreign debt grew three times from US$23 billion to US$65.3 billion in the same period (Borisov, 2002). Reliance on financial legacy allowed some borrowing from abroad in the interim but not for long.

Figure 1.2 USSR internal debt, Soviet roubles billions (1975–1990) (source: author’s calculations based on data from Shatalin et al. (1990)).

Unconstrained money growth (reaching double digits according to estimates in Shatalin et al., 1990) was not supported by the real economy’s needs, which grew at a much slower pace. As a result, despite the best intentions, nominal wage increases were almost immediately negated by surpassing inflation. Further, money emission was supposed to help jumpstart the stagnated economy via increased investments in the manufacturing sector. However, that mainly led to half measures and projects were eventually abandoned due to an inability to sustain consistent investment flows and the lack of realistic incentives for nominal investment project managers. By the early 1990s, consumer goods and durable goods deficits became rampant and seemed incurable. To tackle the problem head on, the government conceded to pressures of the young liberal economists who advocated unambiguous market reforms, departing from the country’s socialist foundations. While explanations of the late 1980s–early 1990s’ social and economic crisis in the USSR are abundant and proliferate, there are several important aspects that are seldom mentioned. These problems are addressed in the next section of this chapter.

1.3 What Happened in the 1990s: More on Political Economy

The Soviet government sponsored a comprehensive analysis of the economy and development of pragmatic solutions that would help revert the country’s downward path. The official transformational blueprint became known as the 500 Days Program. It...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1. Economics of transition in the new century: lessons learned and a future outlook

- 2. Fiscal policy in the newly opened economies: are there twin deficits?

- 3. Fiscal policy sustainability in transition: is it there?

- 4. Innovative fiscal policy: the how, when, and why of borrowing from the diaspora

- 5. Innovative fiscal policy: tackling labor migration problems

- 6. J-curve: facing exchange rate and current account fluctuation risks in the open economies of the CIS

- 7. A model of fiscal policy, currency crisis, and foreign exchange reserves dynamics

- 8. Fiscal policy lessons for the CIS beyond the economic crisis of 2008–2009

- Final remarks

- End notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Innovative Fiscal Policy and Economic Development in Transition Economies by Aleksandr Gevorkyan,Aleksandr V Gevorkyan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.