“Forget everything I have said and wrote. The world has changed.” Brazil’s President Fernando Henrique Cardoso allegedly made this statement after he entered politics. He had supposedly disavowed his former work after adopting several policies that his critics characterized as an embrace of neoliberal economic philosophy. Accusations that Cardoso was pushing policies that he had once critiqued in his previous career as an academic seemed like direct attacks on his character. Before entering politics, Cardoso had achieved international recognition as a sociologist for his work on socio-economic development. In his academic work, he argued that Latin America’s colonial past and continued ties to advanced capitalist economies presented formidable obstacles towards achieving widespread improvements to Latin Americans’ well-being. His writings informed what is known as dependency theory, which was a popular way of explaining the failures and prospects of development in the 1970s.

During his presidency from 1994–2001, Cardoso’s opponents on the left argued that his economic policies would reinforce Brazil’s subordinate position in the world economy and stifle efforts to achieve sustained growth and a more equal society. These critics argued that Cardoso’s support for privatizing state-owned firms and monetary policies based on large capital inflows would increase the country’s dependency. With these policies, Brazil’s economic development would continue to be stunted and historic socio-economic disparities would never be addressed. In his defense, Cardoso reiterated that he never told anyone to forget his former academic work and that his writings on dependency were completely valid for the specific “situations” he sought to illuminate decades ago. In other words, specific conjunctures in the world historic economy provide different opportunities for economic growth and space for governments to enact policies to ensure equitable distribution of the fruits of development. Specifically, he argued that today’s multipolar world whereby no one country dominates the international economy allows for more space for governments to pursue social democratic objectives (Cardoso 2009). The counterargument is that the rules of the global economy favor the powerful at the expense of social justice.

This chapter reviews the theories and writings of Cardoso and other scholars in order to develop an analytical framework for understanding the origins, challenges, and contests surrounding Brazil’s policy of providing high-cost AIDS medicines. I argue that the structural-historical lens developed by dependency theories offers an insightful viewpoint for understanding strategies to increase policy space related to a country’s AIDS treatment program. Specifically, the analytic framework sheds a critical light on contemporary institutions and social inequality, the indeterminacy of political actions, and alternative possibilities (Heller, Rueschemeyer, and Snyder 2009). However, applying the dependency perspective requires a number of caveats regarding the theory’s shortcomings, such as conceptual clarity and lack of attention to social movement actors.

An Analytical Framework for Understanding Pharmaceutical Autonomy

The concept of pharmaceutical autonomy I use throughout this book refers to a country’s ability to fulfill the prescription drug needs of its populations, especially in the face of structural constraints. As an ideal type, the concept also encompasses all the stages in the research, production, and distribution of essential medicines. At the research stage, pharmaceutical autonomy involves the application of resources into discovering and developing treatments for diseases that most burden a society. Next, autonomous capability at the production stage, including the combination of various raw materials at various steps in the manufacturing process, ensures the availability of medicines at suitable prices. Given the limitations imposed by scale economies, not every country can develop an integrated pharmaceutical base. But having firms that can enter a product line and increase competition can lead to lower prices and reduced monopoly power.

In terms of distribution, pharmaceutical autonomy refers to effective health systems that can ensure that essential drugs reach consumers and can guarantee their rational use. Health systems should include qualified doctors, nurses, and pharmacists to diagnosis ailments and administer treatments; regulatory oversight to police substandard drugs; and logistics systems to ensure safe, timely, and effective delivery of medicines. Needless to say, pharmaceutical autonomy implies access to essential medicines regardless of one’s social class, sexual orientation, race, gender, or type of disease. Fulfilling a population’s medical needs thus requires an inclusive institutional framework—such as laws, national Constitutions, and international treaties—that outline the roles and responsibilities of various actors in society to ensure universal access.

Pharmaceutical autonomy is the opposite of pharmaceutical dependency. In previous studies of the pharmaceutical industry, Gereffi (1983) recognized dependency as inequitable distribution of benefits and reduced policy options available to government. Countries that are dependent on the research prerogatives of foreign scientists and firms, have no production capabilities, lack developed health systems, and have weak institutional settings experience higher disparities in access to essential medicines and reduced policy space to pursue public health objectives. More importantly, strong political coalitions necessary for formulating, implementing, and sustaining universalistic pharmaceutical policies are not likely to develop.

The objective of this book is to examine the factors affecting the movement between the two ideal types of pharmaceutical dependency and autonomy. What accounts for Brazil’s broadening of its policy space and its overcoming pressures from the transnational drug industry? And conversely, what factors constrained policymakers from taking more aggressive actions affecting distributional gains and losses? Focusing on just one sector—pharmaceuticals—allows for the exploration of the linkages and distributional consequences between production and access, including the role of both industrial and social policies to discern the evolution of Brazil’s socio-economic development. In more general terms, what does the Brazilian case tell us about the structure of the international political economy and the nature of domestic politics for achieving social democratic goals in the developing world through time? An idiographic case study of Brazil’s AIDS treatment program will allow us to compare current and past social structures (Stake 1995; Yin 1989).

To interrogate Brazil’s pharmaceutical autonomy, my account draws from Haydu’s approach to analyzing history and policy outcomes (Haydu 1998, 2010; Howlett and Rayner 2006). In applying this framework, my narrative of historical events focuses on the “the connections between events in different time periods as reiterated problem solving” (Haydu 1998: 341). The methodology seeks to uncover casual sequences not only by comparing discrete periods of time to discern important variations but also by placing these time periods into broader temporal trajectories. As such, “reiterated problem solving” differs from path dependency models in their understanding of public policies. While both models emphasize the importance of previous historical events as shaping subsequent actions, Haydu’s method views important turning points in history, known as “crucial junctures” in the path dependency literature, not as historical accidents but as developments rooted in previous historical trajectories (Howlett and Rayner 2006).

Explanation in path dependency begins with the “critical juncture” in which prior historical experiences cannot explain the contingent nature of an event. A critical juncture often cannot be predicted or foreseen based on prior events. In these moments, uncertainty and agency often determine the subsequent flow of events and historical processes. After a critical juncture, powerful lock-in mechanisms are set in motion that rule out the possibility of moving on to a new historical pathway. For example, a critical juncture marks the introduction of the QWERTY keyboard, which, despite its inefficiencies in typing, remains to this day due to lock-in mechanisms such as feedback loops and social entrenchment through the keyboard’s widespread adoption in society (Mahoney and Rueschemeyer 2003).

Despite its merits in demonstrating how history constrains subsequent options, path dependency models have two methodological problems. First, the approach has difficulty in addressing broader historical processes that transcend time periods encompassing various discrete critical junctures and lock-in mechanisms. Second, and perhaps more importantly, path dependency provides little conceptual space for historical reversals (Haydu 2010). For example, lock-in mechanisms should prevent a country that transitions from an authoritarian regime to a democracy to switch back into a dictatorship. The path dependent model employed by Nunn (2008) to understand Brazil’s AIDS treatment policies faces difficulty in understanding the various policy reversals regarding the introduction of neoliberal reforms. For example, in the 1990s the Brazilian government dismantled industrial policies and introduced patents for the pharmaceutical sector only later to re-introduce state initiatives for the sector and re-work patent laws from the turn of the century onward.

Haydu’s “reiterated problem solving” does not analyze time periods as discrete units of analysis separated by crucial junctures and lock-in mechanisms. Instead, the methodological approach focuses on how actors face recurring problems over time (Haydu 1998, 2010). In the case of Brazil, the question was how to maintain the sustainability of its AIDS treatment program with increasing number of enrollments each year and high prices charged by the introduction of patented medicines. The “sequence of problem solving” traces how the various “multiple causal trajectories—such as fleeting political opportunities, slower-moving changes in economic resources or strategic allies, and long-standing cultural repertoires—are brought together in episodes” (Haydu 2010: 32). A close case study of the Brazilian AIDS treatment program thus considers the evolution of the country’s technological capabilities, entrenchment of political alliances, and intersection of cultural frames with political opportunities.

My account focuses on the recurrent episodes from 1991 to 2011 in which Brazil faced the problem of procuring high-cost antiretrovirals (ARVs). My detailed analysis of these two decades reveals swings between pharmaceutical autonomy and dependency, and in doing so, reveals the current nature of the contemporary global economy and available policy space for achieving broad-based development. But in order to do so, these recurrent episodes are situated within a broader account of the trajectories of the international pharmaceutical industry and Brazil’s domestic institutions in recent decades. In contrast to Nunn’s approach focused on critical junctures, I analyze the multiple technological, political, and normative trajectories through different “situations” of dependency over a 40-year period. The advent of new global trade regimes, new communication technologies, and the rise in democratic politics present new constraints and opportunities with what Wade (2003) calls a country’s “development space” compared to previous situations of dependent development.

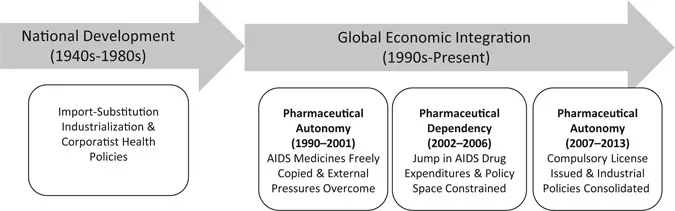

Figure 1.1 provides a broad outline of my argument. The decades from approximately the 1950s to the 1980s represent a distinct timeframe of “national” development. During this conjuncture, Brazil grew its pharmaceutical industry using policies based on import-substituting industrialization (ISI) development strategies. Military rule from 1963 to 1985 dominated the political scene, and social policies favored those with formal employment. The country experienced significant changes during re-democratization in the 1980s. From the 1990s onward, the government introduced new social policies based on broad social democratic criteria and, concomitantly, implemented various neoliberal economic reforms that removed various protective measures against foreign competition, thereby integrating the country into the global economy.

Figure 1.1 Broad Historical Conjunctures (1940s–1980s and 1990s–Present) and Short-Term Episodes (1990–2013) in Brazil’s Pharmaceutical Autonomy

During the subsequent period from the 1990s onward, the “global turn,” I trace three key processes affecting Brazil’s pharmaceutical autonomy: the development and decline of technological capabilities; creation and maintenance of political alliances; and strategic use of normative framing. This conceptual framework draws from traditional sociological concerns that relate to the economic, political, and symbolic dimensions of social power. Importantly, these processes can be traced back to the earlier period that predates Brazil’s change in its political economy. In the three subsequent periods, I demonstrate Brazil’s achievements and challenges in achieving pharmaceutical autonomy when it first rolled out AIDS medications. In the first period (1990–2001), the country developed Brazilian copies of ARVs and overcame external challenges to its patent policies. In the subsequent period (2002–2006), Brazil experienced more dependency due to the inclusion of high-cost medicines and reduced capabilities to produce local medicines, demonstrating the limits of previous political strategies. In response to these constraints, activists inside and outside of the government initiated new forms of coalition building premised on the roll out of new industrial policies for the pharmaceutical sector in the final period (2007–2013).

Technological Capabilities

A key component for achieving pharmaceutical autonomy involves local control over technology necessary to provide essential medicines required by society. Scholars of dependency theory recognized that technology, markets, and trade are intertwined, not as apolitical arenas for exchange, but as fields of power where actors dispute the control of society’s economic resources. In the 1970s, Cardoso and others coined the term dependent development to understand the new structure of the political economies in Latin Am...