- 242 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This volume explores how advances in the fields of evolutionary neuroscience and cognitive psychology are informing media studies with a better understanding of how humans perceive, think and experience emotion within mediated environments. The book highlights interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches to the production and reception of cinema, television, the Internet and other forms of mediated communication that take into account new understandings of how the embodied brain senses and interacts with its symbolic environment. Moreover, as popular media shape perceptions of the promises and limits of brain science, contributors also examine the representation of neuroscience and cognitive psychology within mediated culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Neuroscience and Media by Michael Grabowski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Brain on Media

1

Neuromediation

An Ecological Model of Mediated Communication

Understanding mediated communication involves building a model that conforms to the observed environment and correctly predicts its influence upon that environment. Oftentimes, these models are limited by the questions that are asked: How efficient is a channel of communication? What information is transmitted? What meanings are generated? How do people use media? How do media shape culture? Each model is embedded with political, economic, and social assumptions. The words sender, user, player, actor, spectator, audience, viewer, and participant each presuppose how people interact with media. The metaphors we use to describe media bring with them associations that may obscure instead of clarify understanding. Messages do not flow through a pipe (unless the sender is using pneumatic tubes), we do not “hand off” a message electronically, and our brains do not fill up with information poured into it, although it may feel like that at times.

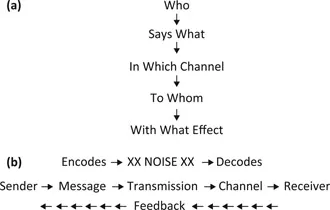

Of course, no model, by definition, can exactly reproduce the environment it represents. Models need only be good enough to address the questions concerning those who use them. As a journalist who saw firsthand the efforts of propaganda crafters during World War I, Walter Lippmann sought a means to use mass media in order to influence public consent of governmental policies.1 Likewise, Harold Lasswell analyzed the effectiveness of wartime propaganda,2 and he established a widely used model of propaganda that served as a precursor to a systematic study of communication.3 His model (Figure 1.1a) incorporated a sender, channel, and receiver but also included the effect of any communicated message, consistent with his study of the effectiveness of propaganda. Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver’s transmission model of communication (Figure 1.1b) served engineers well as they sought to explain the capacity of a channel for transmitting signals.4 Concerned with the ability of electromagnetic systems to successfully preserve information despite the introduction of noise into a signal, these mathematicians reduced communication to the sending and receiving of messages. Norbert Wiener’s contribution to the model completed the loop, confirming transmissions are successful by providing feedback to the sender. By reducing communicators to senders and receivers of information, early communication theorists could work on the problem of channel capacity for telephony and radio communication. The efficiency and accuracy of messages became the focus of communication theory.5

Figure 1.1 Traditional Models of Communication: (a) Lasswell’s Model and (b) Shannon-Weaver-Wiener Transmission Model

Theorizing communication as information transmission and reception became a framework for several branches of communication studies, including the dominant field of effects research.6 Some theories, like political economy, gatekeeping, framing, and agenda setting, focused on the senders of messages. Content analysis examined the messages themselves, and uses and gratifications, audience analysis, and cultivation theory concerned themselves with receivers. Debates centered on (and continue to be argued over) issues like the efficiencies of message transmission, the limited effects of communicated messages,7 concentrated power over communication channels,8 or the power of audiences to construct the messages they receive.9

However, the transmission model fails to address other uses of communication. For instance, people often engage in forms of communication not to send information unknown to the receiver, but as part of a ritual that reinforces group identity and confirms a worldview. Media critic James Carey argued that communication exists within a context of “social processes wherein symbolic forms are created, apprehended, and used.”10 His ritual model asks qualitative questions about the symbolic systems employed to comprehend and understand definitions of reality. Arising out of his concern of how the juxtaposition of mass media and traditional human communication form a democratic culture, Carey’s model is a culmination of critical theory and cultural studies, which both question the assumptions behind the traditional transmission model.

As effects researchers focused their attention on the messages communicated across channels of communication, another theorist asked how the channels themselves acted upon cultures. Marshall McLuhan’s aphorism “the medium is the message” may suggest that his theory fits squarely within the channel portion of the transmission model, but that would misrepresent both McLuhan’s concerns and the model he constructed to address them. Rather, he argued that messages themselves were largely irrelevant in the shaping of culture. For McLuhan, messages were “… like the juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind.”11 Instead, the dominant media cultures use to communicate structure that culture around specific sense ratios. McLuhan relied upon Harold Innis12 to show that media possess different biases as they extend in space and time. Just as other technologies extend and amplify parts of the human body (a hammer extends the fist, an automobile extends the legs), media act as extensions of the human perceptual nervous system, according to McLuhan. A photograph extends the eye, and radio extends the ear.

Critics of McLuhan wrongly saw his work as an embrace of electronic media and an attack on intellectual culture13 or a form of technological determinism that discounted human intervention.14 Yet, McLuhan asserted that media technologies are not deterministic in and of themselves. Rather, they have deterministic effects because their users are unaware of those effects. McLuhan referred to the myth of Narcissus to illustrate this point. Narcissus did not fall in love with himself, but with a reflection of himself, which he saw as another being. Narcissus was unaware that the object of his love was his own construction. McLuhan characterized this condition as a form of narcosis, an autoamputation of senses to which a person is oblivious.15

McLuhan observed that a new medium changes the entire sensory environment into which it is introduced. Media change sense ratios, altering the perception of one’s environment. One of his students, Neil Postman, popularized McLuhan’s ecology of media ecology. Postman defined media ecology as

… the study of information environments. It is concerned to understand how technologies and techniques of communication control the form, quantity, speed, distribution and direction of information; and how, in turn, such information configurations or biases affect people’s perceptions, values, and attitudes.16

Unlike previous models discussed earlier, media ecology maintains that changes in the media environment are not additive but ecological. A new medium changes not only the messages sent through it but the entire symbolic system in which it exists. Like the physical ecology of a biome, the symbolic ecology of an information environment reacts to the interaction of media within that environment.17

Media ecology addresses the question of how media extend our perception, but how do our senses perceive our mediated environment? Since McLuhan wrote Understanding Media, neuroscience has moved beyond a hemispherical model of the brain to map out several regions with specialized functions. Tools like electroencephalography (EEG), positron emission tomography (PET), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), and magnetoencephalography (MEG) have allowed researchers to observe brain function in real time and with increasing resolution.18 Cognitive psychologists began to work with systems neuroscience and brain imaging to link perception and behavior to biological and neurological responses. With this new understanding, any theory of mediated communication should take into account how the brain processes symbolic forms. Media ecology serves as a good starting point for this inquiry.

If we think of the brain as a medium through which we process information about our environment, a media ecological analysis would ask in what manner its properties influence how that information is processed. Like a body of water that bends the light which passes through it, the structures of the brain shape and process perceptions according to the neural networks they have formed. Mediated communication has tapped into these perceptual systems and exploits the characteristics of those systems. I have chosen to call this process neuromediation.

Like other models of communication, neuromediation addresses specific questions: How does each medium engage with our perceptions? What internal brain structures generate meaning from perceived mediated symbols? Which regions of the brain attend to different symbolic forms? How do the physical forms of symbols (what semioticians would call signifiers) and their context influence how they are processed? What information does the brain ignore when attending to media? In its essence, neuromediation concerns itself with the relationship between media and the brain.

This model relies on several advancements in brain research. First, it takes into account the fact that the brain is made up of a complex of suborganal structures. Advances in brain mapping have moved beyond the function of gross structures (brain stem, cerebrum, cerebellum) to a complex network of brain regions, such as the amygdala, basal ganglia, hippocampus, hypothalamus, thalamus, and cortical areas. The cerebral cortex consists of frontal, parietal temporal, and occipital lobes, each of which is further divided into regions that serve specialized functions. Localized structures correlate with specific activities, like the fusiform face area, which is involved in facial recognition and object categorization; Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, related to language recognition and speech production; the hippocampus, used in the formation of memories of novel events; and the nucleus amygdalae, which process and regulate emotions like fear and pleasure.19 In addition, researchers better understand paths of neural activity, like auditory processing from the cochlear nucleus to the superior olivary nuclei to the inferior colliculus through the medial geniculate nucleus to the primary auditory cortex. Sound perception, in fact, takes two pathways: a ventral stream helps in identifying sounds, while the dorsal stream helps to locate the origin of sounds. Visual information travels along the optic nerve through the optic chiasm to the lateral geniculate body to the visual cortex in the occipital lobe.20 Moreover, researchers have mapped out the V1 area of the visual cortex and demonstrated a retinaltopic relationship. Computational brain imaging has devised a method for reading neural activity in this area and reproducing an approximation of what that area “sees.”21 Although neuro-science is far from mapping every neural network, enough is already known to inform communication theory and provide a more detailed model of the interaction between the brain and media.

Second, the model adopts the hypothesis that the brain is embodied. Several neuroscientists, including Antonio Damasio22 and Joseph LeDoux,23 have argued that cognition, emotion, and the body function together to create a sense of the self. A long philosophical tradition of embodiment has linked brain and culture with some debate.24 More conservatively, this model refers to the extension of the brain through the sensory and motor nervous system and the endocrine system, which secretes neurotransmitters like dopamine, somatostatin, oxytocin, and vasopressin. Changes in these systems are reciprocal: motor action is perceived by the vestibular, proprioceptive, and haptic senses, and secretions of some hormones lead to neural activity that triggers other neurotransmitters. Some...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART I The Brain on Media

- PART II Media on the Brain

- Contributors

- Index