eBook - ePub

Information Systems for Emergency Management

- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Information Systems for Emergency Management

About this book

This book provides the most current and comprehensive overview available today of the critical role of information systems in emergency response and preparedness. It includes contributions from leading scholars, practitioners, and industry researchers, and covers all phases of disaster management - mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. 'Foundational' chapters provide a design framework and review ethical issues. 'Context' chapters describe the characteristics of individuals and organizations in which EMIS are designed and studied. 'Case Study' chapters include systems for distributed microbiology laboratory diagnostics to detect possible epidemics or bioterrorism, humanitarian MIS, and response coordination systems. 'Systems Design and Technology' chapters cover simulation, geocollaborative systems, global disaster impact analysis, and environmental risk analysis. Throughout the book, the editors and contributors give special emphasis to the importance of assessing the practical usefulness of new information systems for supporting emergency preparedness and response, rather than drawing conclusions from a theoretical understanding of the potential benefits of new technologies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE DOMAIN OF EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT INFORMATION

STARR ROXANNE HILTZ, BARTEL VAN DE WALLE, AND MURRAY TUROFF

Abstract: This chapter provides an introduction to this volume, structures the different contributions, and provides a summary of each of the chapters, highlighting what we consider to be the most important contributions and issues. The phases of emergency preparedness and response are reviewed, as is the issue of appropriate research methodology for evaluating new types of emergency management information systems.

Keywords: Emergency Response, Emergency Management Information Systems (EMIS)

Technology that provides the right information, at the right time, and in the right place has the potential to reduce disaster impacts.It enables managers to plan more effectively for a wide range of hazards and toreact more quickly and effectively when the unexpected inevitably happens.—Etien L. Koua, Alan M. MacEachren, Ian Turton, Scott Pezanowski, Brian Tomaszewski, and Tim Frazier (chapter 11, this volume)

SCOPE AND PHASES OF EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT AND THEIR INFORMATION SYSTEMS SUPPORT

Disaster, crisis, catastrophe, and emergency management are sometimes used synonymously and sometimes with slight differences, by scholars and practitioners. We use “emergency management” in the title of this book primarily to refer not to small-scale emergencies such as a traffic accident or a house fire, but rather to disasters and catastrophes (whether from natural causes or from human actions such as terrorist activities). A disaster is defined by the United Nations (UN) as a serious disruption of the functioning of a society, and catastrophes refer to disasters causing such widespread human, material, or environmental losses that they exceed the ability of the affected part of society to cope adequately using only its own resources. Both disasters and catastrophes create a crisis situation: emergency managers must intervene to save and preserve human lives, infrastructure, and the environment. The design, assessment, and impacts of emergency management information systems (EMIS), including information and communication technologies to coordinate and support this intervention, are the subjects of this volume.

Quarantelli (2006) has reviewed how community disasters (used generically to also include the more serious “catastrophes”) are qualitatively and quantitatively different from routine emergencies. When a disaster is declared, at the organizational level alone there are at least four differences:

1. In disasters, compared to everyday emergencies, organizations have to relate quickly to far more and unfamiliar entities, often involving hundreds of different organizations. Coordinating information and actions becomes very complex.

2. Since community crisis needs take precedence over everyday ones, all groups may be monitored and given orders by disaster management entities that may not even exist in routine times.

3. Different performance standards are applied; for example, triage at emergency sites has the goal of saving the maximum number of lives given only the medical resources that are immediately available or expected before there is a significant probability that a casualty will die.

4. The dividing line between “public” and “private” property disappears; private goods, equipment, personnel, and facilities may be appropriated without due process or normal organizational procedures.

A catastrophe is a disaster with a much more severe and widespread level of devastation. In a catastrophe, much of the housing is unusable, most if not all places of work, recreation, worship, and education such as schools totally shut down. The infrastructures are so badly disrupted that there will be stoppages or extensive shortages of electricity, water, mail or phone services, as well as other means of communication and transportation (Quarantelli, 2006). Local organizations, including the emergency response organizations, cannot function normally, since they lack facilities, and the scope of the catastrophe means that nearby communities that had been counted on to provide assistance are also not available. Thus, “outsiders” such as federal or international organizations must take over.

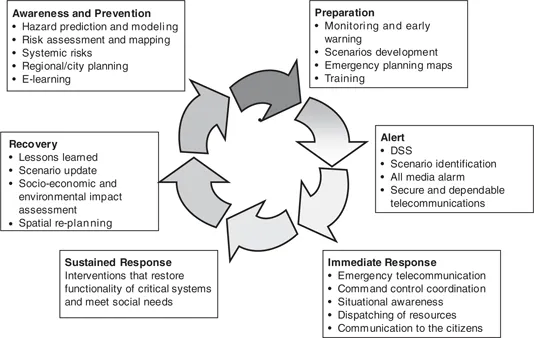

The literature on disaster management typically identifies four to eight phases of the emergency management process (Turoff et al., 2009). Almost all classifications include four basic phases: mitigation (which involves risk assessment as a first step), preparedness, response (also called emergency management), and recovery. Some add identification and planning as the first phase, and/or “early warning” as a separate phase between preparedness and response. Other possible phases that overlap with these main phases include training, immediate preparedness, and evacuation. Planning encompasses all these areas, and many of these functions go on simultaneously depending on conditions and locality within the disaster area. Within the European Union research framework, the European Commission’s Directorate General on the Information Society and Media (DG INFSO) strongly supports the view of an “integrated disaster management cycle,” as shown in Figure 1.1.

Regardless of the specific definition of the various phases, information systems are increasingly important to support the personnel involved. This is particularly true given new types of information systems and technology, for example, wireless mobile Internet that can provide worldwide connectivity to distributed teams for disaster planning and response, and geographical information systems that can integrate up-to-date satellite photos and maps of affected areas with tagging and reporting and uploading of real-time data by citizens. Examples of the use of information systems in each phase are given in the various chapters in this volume; we will also review a few here.

Mitigation refers to pre-disaster actions taken to identify risks, reduce them, and thus reduce the negative effects of the identified type of disaster event on human life and personal property. For example, geographical information systems can be used to identify floodplains for rivers or likely wind patterns that might bring fires to areas such as the canyons of Southern California. Once a geographic area at risk is identified, steps can be taken to decrease these risks, such as new zoning to prevent construction in a floodplain, or fireproof roofs being required for new construction in a wildfire-prone area.

Figure 1.1 | The Integrated Disaster Management Cycle |

Source: Senior EU project officers from DGINFSO have presented Figure 1.1 at numerous EU project and public information meetings. It is reproduced here with permission from its original author, Guy Weets at DG INFSO.

Preparedness refers to the actions taken prior to a possible disaster that enable the emergency managers and the public to be able to respond adequately when a disaster actually occurs. For example, personnel can be trained using computer-generated or -supported simulations or exercises. Web sites can be created to direct citizens about what to do in different disaster circumstances and how to prepare their families, for example, by having a two-week supply of water, food, medicines, and other necessary materials stored in their homes, or map-based indications of evacuation routes for events such as floods or fires. Preparedness also includes having adequate information systems up and running and practicing with them so that they can be used for command and control to coordinate emergency personnel and locate resources and keep track of the location of evacuees, for instance.

The response phase includes actions taken immediately prior to a foretold event, as well as during and after the disaster event, that help to reduce human and property losses. Examples of such actions include placing emergency supplies and personnel; searching for, rescuing, and treating victims, and housing them in a temporary, relatively safe place. Information systems are crucial for coordinating the efforts to distribute rescue workers and supplies and materials (e.g., water, food, medical supplies, and ambulances) to the locations where they are most needed. Increasingly, citizens are supplying information to online systems that are helpful in this phase, such as by uploading photos of the unfolding disaster or supplying information about missing or injured people.

The recovery phase is sometimes never completed; its objective is to enable the population affected to return to their “normal” social and economic activities. So, for example, recovery would include replacing a destroyed bridge or other missing infrastructure, as well as rebuilding permanent housing that was lost in the disaster. The maps and models included in geographical information systems are important aids in the planning and management of a recovery process.

However, despite the recognition that information systems are crucial components of emergency management, there has been surprisingly little research published that facilitates understanding of how they are actually used in emergencies. There have been a few short overview articles about EMIS (e.g., Van de Walle and Turoff, 2007, 2008), but there are no comprehensive overviews of the field. Our aim is to fill this gap in this volume of studies that will be of interest and value for researchers, practitioners, and students. In the chapters invited for this book, the emphasis was on case studies and data on systems that not only exist but also have been studied in use, so that others can benefit from the lessons learned.

The following section covers the topic of research methods appropriate for documenting and assessing the effectiveness of the use of EMIS, a topic that is not explicitly covered in any of the chapters of this volume. It is meant to sensitize readers to this issue. Then we summarize the chapters in the book, organized according to the divisions we arrived at of foundational chapters relevant to any type of EMIS, chapters related to the characteristics of individuals and organizations that provide the context within which EMIS are designed and studied, case studies of specific types of EMIS, and systems design guidelines. After looking at the summaries, the reader may decide to peruse chapters in a different order or jump to a chapter that seems particularly relevant. The summaries are also meant to highlight what we think are the most important issues and contributions in each chapter.

METHODS OF RESEARCH ON EMIS: REFLECTIONS AND AN EXAMPLE STUDY OF EARTH OBSERVATION TECHNOLOGIES

One of the emphases of this volume is the importance of assessing the usefulness of new information systems for supporting emergency preparedness and response, when applied in practice, rather than just drawing conclusions from a theoretical understanding of the potential benefits of new technologies. This is particularly important in the case of crisis response applications, the use of which is embedded in complex socio-technical systems that often cross many national and organizational boundaries.

Case and field studies that include qualitative research methods are especially appropriate for both formative and summative evaluation of new and evolving systems that do not yet have a large number of users. By formative evaluation is meant research that is designed to provide feedback to further improve the usability and usefulness of a tool. By summative evaluation is meant an overall measure of “how good is this system,” particularly as compared to other alternatives, including manual methods. No one method of data collection is likely to be sufficient for system evaluation; a combination is likely to be necessary. All of the authors of chapters in this volume about specific systems were asked to include a discussion of the methods and findings of evaluation research on their systems. Some chapters provide more information than others do about research methods; in this section, we highlight one chapter that used a variety of assessment methods.

Qualitative research methods used during a large-scale simulation and recognition of how the use of information systems during crises is part of a socio-technical system are important aspects of “Do Expert Teams in Rapid Crisis Response Use Their Tools Efficiently?” (by European scholars Jiri Trnka, Thomas Kemper, and Stefan Schneiderbauer). This chapter reviews experiences and lessons learned from a simulation of operational deployment of earth observation technologies by expert teams in rapid crisis response. By “earth observation technologies” [EOT] is meant advanced geospatial technologies, such as space-based sensors, unmanned aerial vehicles, high volume data processing tools, and integrated geospatial databases which can be used in detailed real-time mapping to obtain a fast and reliable situation assessment when crises occur.

The research focus of this chapter is thus laid on gaining knowledge of operational deployment of EOT by expert teams in rapid crisis response. In many situations, simulations, as a methodological means of studying human systems or their parts, are the only way for the research and development community and the prospective users to confront and analyze these situations and systems. The simulations that are relevant in the emergency context are those with humans in the loop—interactive multi-person settings reproducing reality or its parts (Crookall and Saunders, 1989). They replicate situations and processes, where simulation participants (humans) try to solve a problem or overcome various obstacles in a collaborative manner. This type of simulation has been widely used in the military and crisis management domain. In these simulations, participants act based upon hypothetical conditions (defined via scenarios), while using real and simulated resources. The simulations described in Trnka et al.’s study were executed in real time, but are referred to by the authors as “low-control” simulations in the form of case studies. The focus of data collection and analysis is given primarily to qualitative data and qualitative analysis on how different interactions and processes took place.

The scenario created for the study reported in Trnka and colleagues’ chapter was an incident in a nuclear power plant followed by a release of radioactive gasses. Each team had one predefined coordinating organization operating at a coordination point; the simulation was executed at fourteen different locations in nine countries over a period of thirty-three hours. There wer...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Series Editor’s Introduction

- 1. The Domain of Emergency Management Information

- Part I. Foundations

- Part II. Individual and Organizational Context

- Part III. Case Studies

- Part IV. Emis Design and Technology

- Editors and Contributors

- Series Editor

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Information Systems for Emergency Management by Bartel Van De Walle,Murray Turoff,Starr Roxanne Hiltz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.