![]()

Chapter 1

INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC OF THE BIBLE

Terracotta relief depicting a musician playing a vertical harp. Old Babylonian period, ca. 2000–ca. 1550 BCE (Iraq Museum, Baghdad)

Of all ancient literary and historical monuments the Bible contains the fullest information about the musical instruments that existed in those remote times. It accumulated the treasure of musical traditions of several great ancient civilizations including the rich store of their instruments. It came into being at the intersection of different cultures, comprising a vast geographical region from Mesopotamia to Egypt and to the border of Asia Minor. Therefore the Bible could without any exaggeration be called the first encyclopaedia of the musical instruments of the ancient Near East.

Musical instruments are mentioned in no less than 25 books of the Hebrew Old Testament1 in a total of 146 verses, as counted by E. Kolari. The concrete realities of ordinary life in biblical times (animals, insects, plants, precious stones, etc.) are often little known, and hard to understand, and musical instruments certainly belong in this category. Though at first sight there are relatively few names, and they seem to refer to similar instruments, nevertheless when studied in depth they turn out to belong to several different families, and in comparison with other ancient cultures, are rather numerous. They form an integral and valuable part of ancient musical culture, and represent the whole range of ancient instruments.

The Tanakh (the list of canonical books according to the Jewish tradition) contains the names of about 20 musical instruments. However, despite a large range of information, with rare exceptions it never gives any explanation or comments on their typology, etymology or technical characteristics. That is why the investigation of these questions entails numerous difficulties, and raises problems which are often impossible to solve by the sole means of historical or theoretical musicology. It is necessary to draw on other disciplines, such as archaeology, source criticism, comparative linguistics, and comparative organology. The complex analysis of the Old Testament instrumental terminology based on the principles and methods of research worked out in these disciplines will help in attaining positive results.

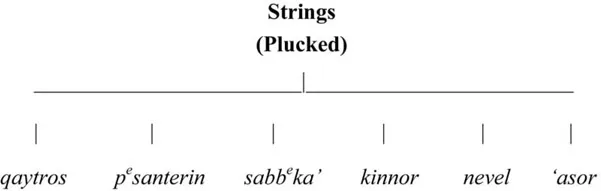

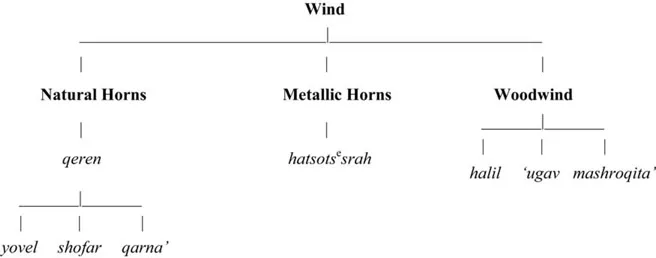

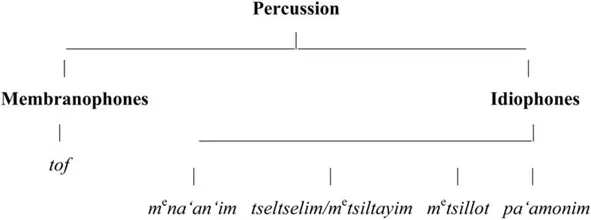

Thus the class to which an instrument belongs has been defined by modern Bible scholars with some confidence. The main classes are strings, wind instruments, and percussion. The stringed instruments all involve plucking (rather than bowing) and include kinnor, nevel, ‘asor, qaytros, pesanterin and sabbeka’. The wind instruments are divided into three subclasses: natural horns, metallic horns, and woodwind. Natural horns include the qeren and its varieties shofar, yovel and qarna’. The only metallic horn is the trumpet hatsotserah. The woodwind subclass includes halil, ‘ugav and mashroqita’. Percussion instruments are divided into two subclasses: membranophones and idiophones. The only membranophone is the tof. The idiophone subclass includes mena‘an‘im, tseltselim/metsiltayim, metsillot, and pa‘amonim (see Diagrams 1-3). Suitable English names for the instruments will become apparent in Chapter 2.

Along with these there are many terms whose class membership is still debated. Among them are sumponiah, shalishim, mahol, sheminit, nehilot, neginot, gittit and shushan. Their assignment to classes will be discussed later, and suggestions will be made in each case.

The first reference to music comes at the beginning of the Bible story, in the passage concerning Jubal, “the father of all those who play the lyre and pipe” (Gen. 4:21).2 The last instrument named is metsillot (Zech 14:20). The historical books of the Tanakh (1–2 Sam., 1–2 Kgs, 1–2 Chr.) and the book of Psalms are the richest sources of references to musical instruments. Some sections are replete with instrumental terminology (1 Chr. 15:16, 19, 20, 24, 28; Ps. 150, Dan. 3:5, 7, 10, 15). Instruments are used both independently (mainly the shofar: Lev. 25:9; Josh. 6:4-6; Judg. 3:27, etc.) and as members of various ensembles. The latter may be homogeneous, comprising either the plucked string group, kinnor (lyre) and nevel (harp) in Ps. 57:8; 71:22, or wind instruments, shofar (horn) and hatsotserah (trumpet) in 2 Chr. 15:14; Ps. 98:6, or percussion, tof (tambourine) and shalishim (sistrum) in 1 Sam. 18:6. The ensembles may also be heterogeneous, having different combinations of the instruments: kinnor, nevel, tof, mena‘an‘im (sistrum or rattle), tseltselim (cymbals) in 2 Sam. 6:5; kinnor, ‘ugav (flute), tof in Job 21:12; nevel, kinnor, hatsotserah in 2 Chr. 5:12. Occasionally the instruments form a substantial ensemble.3 Such for instance is a band of the prophets (1 Sam. 10:5) which, according to the biblical text, already existed during the reign of Saul (ca. 1030–1010 BCE) and included three “classical” groups of instruments: strings (kinnor and nevel), woodwind (halil: double reed) and percussion (tof). The instruments accompanied the daily procession that took place after the sacrificial rite at the altar. The court musicians of King David (ca. 1010–970 BCE) also contained as an obligatory element of the service the same three instrumental groups: strings (kinnor and nevel), wind (hatsotserah) and percussion (metsiltayim) in 1 Chr. 15:28. The court musicians of King Nebuchadnezzar II (sixth century BCE) included Babylonian analogues to the ancient Jewish instruments (Dan. 3:5, 7, 10, 15): qaytros, pesanterin, sabbeka’ (strings), qarna’ (brass), mashroqita’ (woodwind). Its sound increased the pomp of the court ceremonies and fitted the orgiastic atmosphere of the pagan rituals.

The Hebrew Old Testament contains a good deal of information about the social functions of the instruments. The accompanying of ritual processions, temple services, court ceremonies and cult rites has already been mentioned. Also included was participation in religious feasts and secular festivals (practically all the aforenamed instruments in Num. 10:10; 29:1; 2 Kgs 11:14; 1 Chr. 13:8; Neh. 12:27; Job 21:12; Ps. 33:2), in military campaigns (shofar in Ezek. 7:14; hatsoteerah in Num. 10:9), in greeting a victorious company (tof in Judg. 1:34), in grandiose secular celebrations, such as the ritual of the anointing of kings (shofar in 1 Sam. 9:13; 1 Kgs 1:34), and in the public festivals organized on such occasions (halil in 1 Kgs 1:40; hatsoteerah in 2 Chr. 23:13). Instruments were also used in people’s private lives, when they appealed to God (Ps. 108:2), while celebrating happy family events or funerals (kinnor, nevel, halil, tof in Gen. 31:27; Job 30:31; Matt. 9:23).

It is impossible to trace exactly the chronology of the origin and evolution of the ancient Jewish instruments and instrumental music. The main phases, however, are shown in the Bible quite clearly. Thus it is generally agreed that at the early stage, in the Patriarchal period, along with the kinnor and the ‘ugav, the tof was also known. Its lively rhythm enhanced the joyful atmosphere of greetings and valedictions (Gen. 31:27). On particularly solemn occasions simple instrumental ensembles, consisting mostly of strings and percussion (for instance, kinnor and tof in Gen. 31:27) were in vogue. Also used were the shofar (Exod. 19:13, 16, 19) and the hatsotserah (Num. 10:2). In those days the shofar was already perceived as a sacred symbol (the voice of God) and later interpreted as a musical echo of the divine command (Lev. 23:24; Num. 29:1). The hatsotserah was required by God not only to assemble the community (Num. 10:2-7), but also to be a sign of mediation between himself and the people (Num. 10:9, 10). As for the other instruments listed above, the Old Testament has no direct information about their social roles. Nevertheless this does not mean that such roles did not exist. One should keep in mind that many things in the biblical text can be understood e silentio.

The social life of the period of the United Monarchy (eleventh-tenth century BCE), particularly the role of instrumental music, is represented in many and varied ways. Instrumental performers took part in every significant state, social and religious event. Thus, they were part of the grand procession that followed the Ark of the covenant when it was transferred to Jerusalem (1 Chr. 13:8; 15:16-21, 27, 28). As the sanctification of the first Temple and the installation of the Ark proceeded, they “stood at their posts” (2 Chr. 5:12-13; 7:6). The leadership of the prophet Samuel was marked by an extremely important event which determined the direction of the development of ancient Jewish musical art for the next two centuries: from that time until the reigns of David and Solomon the system of musical education began to be formed in Ancient Israel. The so-called nayyot (lit. “huts”), “schools of prophets”4 were the first step on this path. Here young men and older people, both those having a prophetic gift and those with exclusively musical talent, from different families and social strata, were taught music. Their chief duty was to accompany the sacrifices held “at the high places” (1 Sam. 9:12; 10:5; 1 Kgs 3:2; 15:14; 22:43; 2 Kgs 23:5). At certain (probably peak) moments of concentrated spiritual energy the prophets5 gathered in a band and sang, accompanying themselves on different musical instruments, such as the kinnor, nevel, tof and halil (1 Sam. 10:5). The Bible characterizes such emotionally charged singing as prophecy (“prophets prophesying”, hannevi’im nibbe’im: 1 Kgs 22:12; compare 1 Sam. 10:5, 10; 1 Kgs 22:10). In the years of Saul’s reign, along with the “schools of prophets” there seems to have appeared a new organization of musicians, which gradually replaced the schools of prophets and was transformed by Saul’s successor David into a “music academy” (a quaint but appropriate term given by C. Sachs). It gained a permanent status, possibly in the second quarter of the tenth century BCE, during Solomon’s reign (ca. 970–930 BCE). There the Levites, both singers and instrumentalists, who formed the main body of meshorerim (“ministers of music”, 1 Chr. 15:16), received a thorough training in professional performing, with special orientation to the liturgy. After completing such a course they could devote themselves to sacred musical service, first at the sanctuary, and later in the Temple.

From the very beginning the organization functioned as a guild, where the interrelations were based on strict discipline including total submission to the r...