Introduction

At present many books on research methods focus on the theory of ethics and how to apply it when starting a research project, but there is relatively little discussion on applying research ethics in practice throughout the life of a qualitative research project and the importance of researcher reflexivity to that process. This book focuses on the practice of ethics and how ethical practice can be sustained by researchers in the field throughout the life of research projects using ethnographic and other qualitative approaches to research.

The extension of ethical regulation over the past twenty years from medicine and psychology across the whole of social science has made it more difficult for researchers to explain why ethnographic research in education needs to be carried out in certain ways that often differ from those of medicine and the physical sciences while still being ethically sound. Ethical regulation is largely carried out by research ethics committees, known in some countries as institutional (ethical) review boards, which decide if research projects can be implemented, and on what terms. Other countries, particularly in Scandinavia, have central or national review bodies to support researchers in their ethical thinking and to police their practice.

This regulatory regime has posed problems for ethnographic and other qualitative research because it is based on a medical and physical science model of enquiry. Not least, it pre-supposes levels of potential harm to participants arising from invasive and other physical processes that are highly unlikely ever to occur in qualitative research. However, it is not unreasonable for participants, gatekeepers and beneficiaries of research to wish to be sure that researchers have taken care to act in manners that are intended to prevent harm to participants in, and the environment of, a research project. It has led to a public demand that researchers show that they can sustain auditable ethical practices. Nonetheless, the formal regulatory procedures have introduced significant delays into the inception of research projects, as well as raising questions about the validity of some research designs that are needed for studying human interaction in certain situations. Some researchers have even argued that the new regulatory regime is an infringement of academic freedom to pursue research deemed necessary for understanding social and political processes in society.

The main gatekeepers to whether or not a study is approved to proceed are variously called research ethics committees (RECs) or institutional review boards (IRBs), seemingly depending on which side of the Atlantic you live. Both terms are used in the chapters in this book. They are usually convened by academic institutions to police the quality of research projects proposed by researchers and to ensure the proposed projects meet the ethical protocols supported by an institution and the relevant ethical guidance or codes of conduct of the professional body or bodies in the researcher’s field, and to give researchers confidence that they have the support of their organisation in their work. However, in some Scandinavian countries RECs are not institutionally based but government-based, as some of the chapters in this book illustrate. In addition, researchers might also have to pass their projects through ethical review if their studies are undertaken with funding from sponsors, including government ministries, or in specific research settings, such as within healthcare or prison service settings.

Ethnographic enquiry proposals often face particular challenges when being considered by IRBs as some board members are often unfamiliar with the methodology and how its data collection processes need to be provisional at the beginning of a project. Even if board support is granted based on an agreed set of practices about entry to the field and securing informed consent from potential participants, this does not always help ethnographers as they confront methodological dilemmas in the field (Rashid, Cain & Goez 2015). Once in the field, relationships develop in ways not easy to anticipate and data emerge that are of interest beyond those accessible through initial informed consent to participate in research. This places particular responsibilities on the ethnographer through significant self-reflection on ethical practice (Fine 1993) and also trust in the researcher from the institution.

This book discusses how researchers can carry out ethical educational ethnographic research in a variety of face-to-face public educational spaces, as well as in online and hybrid spaces. This includes researchers persuading organs of research supervision, such as ethical review boards, as well as stakeholders and participants in research projects that they will carry out their research in an ethical manner throughout the life of a research project and afterwards, during its publication phase. It also addresses the dilemmas of people carrying out research in happenstance situations when it might not be clear from whom to gain consent to carry out research, either at the beginning of a project or during the life of a project as the research process develops through time. Yet not gaining this permission raises questions about how responsibly a researcher is behaving.

Contributions to the book focus on how researchers can construct and apply knowledge of ethical practice to ethnographic studies in different educational situations to make clear to putative participants in and gatekeepers of their proposed research projects that these will be carried out in an ethical manner. It also focuses on the dilemmas in the field that educational researchers encounter when trying to enact ethical practice and how they might resolve these. It is intended that this book helps researchers in the field to cope wisely with the ethical dilemmas that they may encounter while also helping ethical regulatory bodies at national and institutional levels to come to wise decisions when faced with research applications that may challenge tightly constructed notions of what constitutes ethical research practice.

Different ethical frameworks/approaches to ethical practice

Ethical decision-making can be considered to operate at five levels (Kitchener & Kitchener 2009), each of which are problematised in chapters in this book.

The first level is related to a researcher’s ethical decision-making in their own research setting through an analysis of the research scenario and their responses. This level is illustrated in this book through different researchers’ perspectives both culturally and personally: Nikkanen’s chapter about her role as a teacher and researcher in a Finnish school (Chapter 6); Smette’s chapter (Chapter 4) and that of Fox and Mitchell (Chapter 8) about the experiences of undertaking ethnographic study of schools in Norway and Ethiopia, respectively; Dovemark’s chapter about the ethical dilemmas faced in studying public recruitment fairs of Swedish schools (Chapter 7). A key argument presented throughout the book is how demanding such decision-making is for ethnographers and in particular how, if researchers are to ethically meet the needs of those they research, entering only with pre-determined ways of behaving underpinned by agreed principles and practices will be insufficient. Decision-making, as for all social science research but argued in this book as a particular concern in ethnographic studies, needs to continue into the fieldwork and reporting phases. This book’s chapters therefore explore how both researcher and regulatory practices need to support researchers in being able to be responsive to their fieldwork experiences to ensure culturally sensitive and ethical studies.

The second level of ethical decision-making refers to the ethical rules bound up in professional codes of practice, ethical guidance and legislative regulations. Such codes and guidance are constructed for the membership of particular professions such as national psychological and sociological associations, broader educational and social science research associations, such as the American Educational Research Association, the UK Academy of Social Science and the British Educational Research Association, as well as formal national bodies that regulate research, e.g., the Economic Social Research Council (UK) and ministries, such as those in Sweden, Finland and Norway. Such guidance is set within a broader legislative landscape relating to issues such as data protection, criminal disclosure and child protection. The codes provide guidance which explain researchers’ legal obligations when carrying out research and need to keep up-to-date with legislative changes.

In Europe, 2018 saw a major launch of new data protection regulation with the General Data Protection Regulation (2018), which affects all those collecting, processing and storing data in the European Union as well as transferring data in and out of the EU and to which national data protection acts have responded with amendments, e.g., the UK Data Protection Act (2018). Institutions within which research is carried out, as well as funding bodies such as research councils (e.g., the National Health and Medical Research Council, Research Council and Vice Chancellors’ Committee in Australia) and national ministries who create ethical codes of practice for their researchers. Together this leads to a web of codified rules that a single researcher needs to navigate and, where the codes appear contradictory, make decisions. The codes are usually regulated by associated review processes ultimately overseen by RECs or IRBs as referred to earlier in this chapter. It is notable that none of these codes are written with any specific methodology in mind and further work is needed by researchers in holding up the various advice they are beholden to against the values associated with their chosen research approach. For ethnographers, this “mean(s) our personal sense of ethics and our ethnographic sense of ethics are not separate from one another” (Dennis 2018: 53). Busher’s chapter in this book (Chapter 5), for example, explores the thinking, rules and practical applicability of the concept of vulnerable participants in the context of educational ethnography.

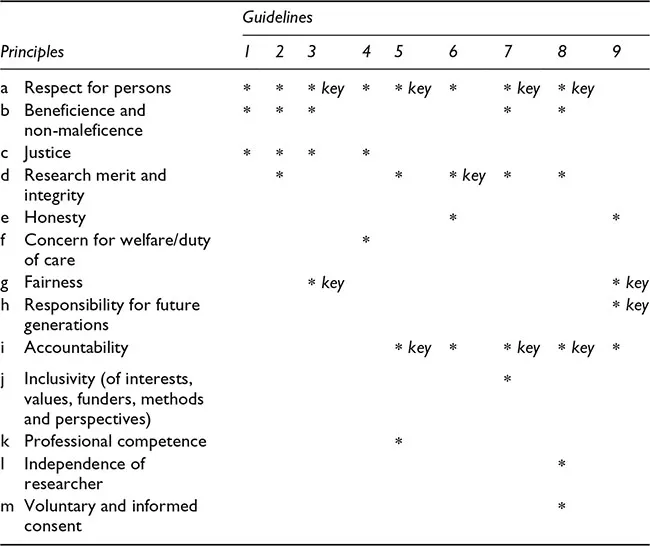

Above the level of codified rules sits a third level of ethical decision-making, that of ethical principles. These underpin the second level to provide a justification for the advice and hence guide first-level decision-making. However, if we look across such guidance internationally there can be seen to be both agreement and difference in the priorities given to the key underpinning principles (see Table 1.1).

In terms of overlap, respect for persons (to be shown in a number of ways), beneficience and non-maleficence (balancing the maximising of benefits against the minimisation of harm), research integrity and accountability feature as common concerns across the most recent versions of these codes. There has been a shift over time as such national sets of principles have been reviewed from their origins in biomedical research. Whilst respect for persons and beneficience can be traced back even before the Belmont report (DHEW 1979) to the Nuremberg Code (1947) and the Declaration of Helsinki (WMA 1964, 2013), the latter two principles of accountability and research integrity have moved into the language of regulation and hence become increasingly explicit in more recent updates. The phenomenon of increasing expectations of researchers to make a social impact has been noted as a modern concern at the regulatory level and one that brings its own challenges in terms of defining and prioritising this against other principles (Mustajoki & Mustajoki 2017). This pushes funding towards applied research, particularly in the case of development aid funding. This could lead to a limitation of what is considered valid research if only simple ‘what works’ studies are funded rather than research that both quests for fundamental understanding and consideration of its use (Wiliam 2011).

Table 1.1 Principles in selected ethical research guidelines

Source: Table largely based on Kitty de Riele (Brooks, de Riele & Maguire 2014: 30–31)

Key

1 DHEW, ‘The Belmont Report’ – 1979 (USA)

2 NHMRC, ARC and AVCC – 2007; updated 2018 (Australia)

3 CNdeS –2012 (Brazil)

a (autonomy); g. (equity)

4 CIHR, NSERC and SSHRC – 2010 (Canada)

a (for rights, dignity and diversity);

i (professional, scientific, scholarly and social responsibility)

6 ALLEA – 2017 (Europe)

d (reliability)

7 BERA and AcSS – 2018 and 2015 (UK)

a (for privacy, autonomy, diversity, values and dignity);

i (social responsibilities for conducting and disseminating)

8. ESRC – 2010; updated 2018 (UK)

a (for rights and dignity); i. (accountability and transparency)

9 World Conference on Research Integrity: Singapore Sta...