- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing Economic Volatility in Latin America

About this book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Managing Economic Volatility in Latin America by R. Gelos in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

2014eBook ISBN

9781484364987Part II: Assessing Reserve Adequacy and Current Account Levels

Chapter 2. International Reserve Adequacy in Central America

International reserve accumulation has recently grown rapidly, reaching 17 percent of global GDP in 2011, which represents a fourfold increase over 10 years. During this time, emerging market holdings rose to 32 percent of GDP.1 This extensive accumulation of foreign reserves has naturally prompted questions regarding what benefits countries have from international reserve holdings, and whether current levels can be justified on economic grounds.

One long-standing view of the rationale for holding international reserves is to insure against balance of payments shocks. Commonly used rules of thumb for reserve adequacy investigate whether international reserves cover some external commitments, for example, three months of imports for countries with limited access to capital markets, or measures of potential capital flight, such as short-term external debt at residual maturity and current account deficits. Alternatively, the actual demand for international reserves has been studied using variants of the “buffer stock model,” treating reserves as a resource for smoothing consumption in the face of sudden stops of external credit and the output falls that often accompany it (Frenkel and Jovanovic, 1981). This strand of literature typically finds that the size of reserve holdings is positively related to income volatility, openness, and financial depth (Edwards, 1983; Flood and Marion, 2002; Obstfeld, Shambaugh, and Taylor, 2008). Previous literature has also tried to find an “optimal” level of international reserves by weighing the aforementioned benefits of international reserves for mitigating falls in domestic consumption during balance of payments crises against the cost of holding reserves—for example, the interest rate differential between long-term debt issued to finance reserves and the return on reserves (Jeanne and Rancière, 2006; Gonçalves, 2007; Valencia, 2010).

Using the above-mentioned frameworks, several authors have concluded that the recent reserve holdings of most emerging markets are hard to justify on economic grounds, and that other factors, such as export-oriented growth strategies, might be at play (Dooley, Folkerts-Landau, and Garber, 2003). Recent evidence from Asia and Latin America suggests that the overaccumulation of international reserves in one country might then have prompted others to follow suit through an attempt to “keep up with the Joneses” (Cheung and Qian, 2009; Cheung and Sengupta, 2011).

Most research on the international reserve coverage has so far concentrated on large emerging markets and advanced economies. This chapter will instead focus on small non-dollarized economies in Central America, that is, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua.2 Our motivation is twofold. First, to provide evidence on reserve coverage for the region—which is lacking—and smaller emerging markets in general.3 Second, to shed light on the appropriateness of the different commonly used methods for assessing reserve adequacy for smaller and less financially integrated emerging markets than those previously studied, including the possible presence of “keeping up with the Joneses” effects.

Our focus region also displays other features that make it an interesting testing ground for assessing reserve adequacy. Compared with some of their larger and more advanced emerging market peers, the Central American economies have, on the one hand, relatively little short-term external debt, suggesting a smaller vulnerability along that dimension. On the other hand, the share of dollar-denominated deposits to total deposits is about 45 percent on average in the region—well above the levels of dollarization in the five largest economies in Latin America and other emerging markets. This gives rise to risks of large deposit withdrawals during crises, which needs to be taken into account when assessing reserve adequacy and has received little attention in the literature.4

Rules of Thumb for Reserve Cover

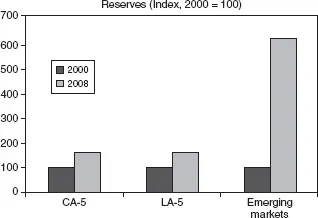

Central America has increased its reserve cover in recent years, though the extensions of coverage were much smaller than those of other emerging markets.5 Although gross international reserves increased by more than 50 percent during 2000–08 in Central America, they jumped threefold in the five largest Latin American economies and sixfold in a larger global sample of emerging markets, as seen from Figure 2.1. In fact, the rules of thumb that follow suggest that Central America’s reserve cover could be strengthened further.

Figure 2.1 Evolution of International Reserves

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics database.

Note: CA-5 = the five largest economies in Central America; LA-5 = the five largest economies in Latin America

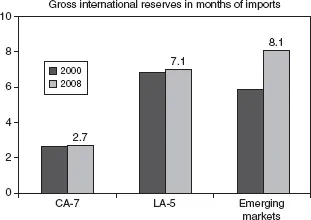

Maybe the most traditional rule of thumb—generally used for countries with limited access to capital markets—is that international reserves should equal three months of imports. As seen from Figure 2.2, this level is barely reached by Central American economies, but exceeded by a wide margin both by the larger economies in Latin America and the full sample of emerging markets.

Figure 2.2 Reserve-to-Import Ratios

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics database.

Note: CA-7 = Central American economies; LA-5 = the five largest economies in Latin America.

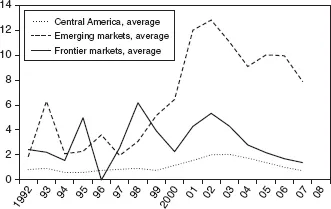

Alternatively, the so-called Greenspan-Guidotti rule states that gross international reserves should cover short-term external debt measured on a residual maturity basis, that is, public and private external debt maturing over the next 12 months (Greenspan, 1999). This rule is often extended to also take into account current account deficits to proxy for total external financing needs and give a more extensive picture of possible capital flight. As seen from Figure 2.3, Central America falls short of the benchmark, despite its relatively modest external debt levels, and in contrast to other emerging markets.

Figure 2.3 Ratio of Reserves to Short-Term Debt and the Current Account Deficit

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics database; and World Economic Outlook database.

Note: Emerging markets refer to countries covered by the JP Morgan EMBI index, except Algeria and Brazil; Frontier markets are countries included in the MSCI Barra Frontier Market Index.

Another often-used rule of thumb is to compare international reserves with the stock of broad money, usually M2. Traditionally, a cover of 5–20 percent of broad money has been considered adequate, but more recently, for example, Obstfeld, Shambaugh, and Taylor (2008) have argued that a sufficient “war chest” should cover up to 50 percent. Regardless of ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- PARTI I | CAPITAL FLOWS AND DUTCH DISEASE

- PART II | ASSESSING RESERVE ADEQUACY AND CURRENT ACCOUNT LEVELS

- PART III | THE ROLE OF MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES AND EXCHANGE RATE REGIMES

- PART IV | FISCAL POLICY

- PART V | MONETARY POLICY AND DEDOLLARIZATION

- Index

- Footnotes